Antoine Hubert, CEO of Ynsect, never expected to become a chief executive. Certainly not back in the days when he was bass guitarist in the experimental heavy metal band Stale Fish, which mixed traditional French accordion music with tortured guitar riffs.

However, playing in a band was good preparation for setting up a startup, he says.

“I think music is a great entrepreneur experience. There are a lot of synergies with creating a band, innovating with songs and lyrics. All these incubators and engineering schools try to teach you how to work together but music is a particularly good way to learn to work in a group for a shared purpose,” he says.

Even later, when Hubert chose agronomy over music as a career, setting up a company was far from his mind. Inspired by the way he had seen New Zealand farms use worms for composting food waste, Hubert became an environmental activist, developing a science education game and visiting schools to evangelise about the importance of insects in the food chain.

Mealworms are non-flying and gregarious. Crickets need more space and are jumping everywhere.

Hubert was convinced that insects should be used far more as a protein source to help feed a world population of 9bn people by 2050 — much as was suggested in the famous 2013 UN report. But soon he started to feel that his small-scale vermicomposting talks were unlikely to change the world.

“Sometimes you are just talking to five people. It is really long and exhausting work, and you don’t see any concrete impact. You are not going to change people’s habits with one or two games. Education is a very long-term thing,” he says.

“We started discussing setting up a company, maybe a restaurant serving insects. But we are not really cooks. So we thought we should go upstream and farm insects, create a market for them.”

This was the start of Ynsect, the French company that is building factories that will farm mealworm beetle larvae at industrial scale, for use in animal feed and as fertiliser.

For all the UN’s exhortations to adopt a bug-based diet, one of the problems with insect farming is economics. Growing insects can be labour-intensive and done on a small scale they have simply been too expensive to compete with other food sources.

But Hubert believed that by using robotics, artificial intelligence and techniques borrowed from vertical farming he can bring costs enough to make this a mainstream protein source.

Ynsect raised $125m in series-C funding in February to finance the building of a new 40,000 square meter vertical farm in Amiens in Northern France, an order of magnitude bigger than the 3000 square meter facility it already has in the Burgundy wine region.

Around 50 insect farming companies have raised a total of $480m to date, but Ynsect, founded in 2011, is among the best-funded of the lot.

Dressed in a brown jacket and brown button-down shirt, his black beard closely trimmed, the 36-year-old father-of-two looks a lot more corporate than in his NGO activist days.

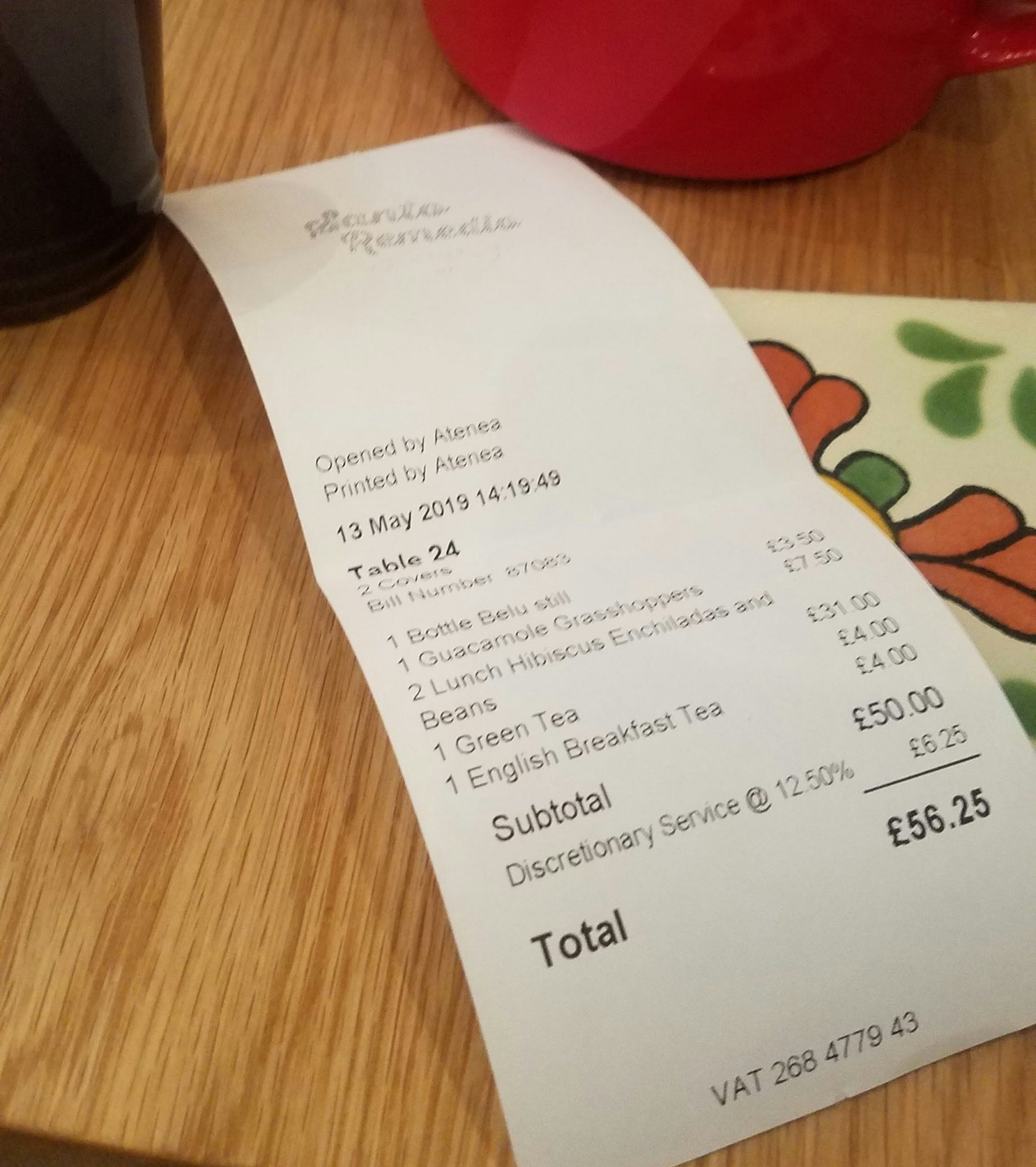

We meet in Santo Remedio in London, close to London Bridge. The Mexican restaurant is one of a handful of eateries in London that includes insects on its menu (we're cheating a little and having lunch rather than brunch because it has proven difficult to find somewhere willing to serve insects for breakfast).

We order the guacamole with grasshoppers, and Hubert does not flinch in sampling them. He is a little disappointed, in fact, that there are so few of them studded in the green mound of avocado. They taste nutty although they are mostly overwhelmed by the guacamole spices. Hubert says he's a fan of the snacks made by French edible insect company Jimini’s, because you can taste a lot of the insect flavour in them — and waxes lyrical about ants' eggs, a delicacy sometimes referred to as “Mexican caviar”.

Ynsect has chosen to farm mealworm beetles, however, because they are one of the easiest species to farm on an industrial scale.

“They are non-flying and gregarious, they love to be together,” he says, showing a video of stacked plastic crates in the Ynsect factory, all full of mealworm larvae wriggling over each other. “Crickets, they need more space individually and of course they are jumping everywhere. If you want to do some automatic feeding you open the box and have them flying everywhere. I don’t think there is a way to cut the costs.”

Hubert is not interested in growing insects for human consumption, either, for all his discussion about the relative culinary merits of crickets and ants. Not only is there still too much of an educational job to be done making insects a mainstream part of western diets, but he also believes Ynsect can have the biggest environmental impact in the $500bn-a-year animal feed market.

He’d like insects to become a replacement for fish meal, which is widely used as a feed for farmed fish, as well as chickens, pigs and cattle. Demand for fishmeal is increasing — it now accounts for around 25% of global fishing — but fish stocks are in decline. Insects could be an environmentally sustainable alternative to fill the gap, says Hubert.

One tonne of insect protein would mean that 5 tonnes of fish in the ocean are protected.

“One tonne of insect protein would mean that five tonnes of fish in the ocean are protected,” he says.

The market for insect-based animal feed is growing slowly. At the moment much of the mealworm powder that Ynsect produces goes into high-end, hypoallergenic food for pampered cats and dogs in western Europe and for use as fertiliser. But European regulation has recently been relaxed to allow fish to eat insect-based protein, with chickens and eventually pigs to follow and these markets are expected to take off.

Eventually, Hubert says Ynsect plans to build 15 factories around the world over the next decade, in North America and South East Asia as well as Europe, producing at 1m tonnes of insect protein a year. That would still be a tiny fraction of the 1bn tonnes produced each year for animal feed, he points out.

Ynsect borrows a lot of techniques used in vertical farms that produce leafy greens. Robots feed the stacked trays of mealworm larvae and rotate them around the factory as they go through their two-to-three month growth cycle, until they are finally dipped into boiling water to kill and sterilise them.

One “secret sauce” that the company has developed is the correct feed mixture for the larvae. They are fed a combination of wheat, corn and potato scraps, byproducts of brewing, milling or sugar production. The right ‘recipe’ optimises the speed at which the larvae will grow and mature.

If you get the feed just right, it can take less than 2kg of these cereal byproducts to create 1kg of insect protein.

If you get the feed just right, it can take less than 2kg of these cereal byproducts to create 1kg of insect protein, a pretty efficient conversion, considering it takes around 7kg of grain to produce a kilo of beef, for example.

We both tuck into Santo Remedio’s hibiscus-flower enchiladas, which are a bit like a much tastier version of red cabbage, but Hubert is no vegetarian. In fact, he’s critical of efforts to create vegetarian meat alternatives, like Impossible Burger or Beyond Meat.

“It is really heavily processed. You need a lot of additives to mimic meat from plants,” he says. “People today think that meat is bad and plants are good, but it is much more complex than that.”

The bigger trend he sees is people reconnecting with their food, cooking more and being interested in the origin of their meals. “Insects can really help animals and plants be more sustainable.”

Hubert may be the “accidental CEO” but he says he adapting well to his new role. He has learned new management skills through a combination of reading, talking to advisors and hiring a personal executive coaching.

But he sees his role as being the “number one salesman” for Ynsect, a job where his activist background is a help.

“The job of a CEO is to sell the company and its mission. It is easier to do this when you deeply believe in what you do. I just want to convince everyone this is a good thing.”

As Ynsect, which now has more than 100 staff, begins to grow rapidly, Hubert is keen to hold onto the original values. He is seeking to certify Ynsect as a B Corporation, an idea that started in the US, where companies commit to pursuing social or environmental goals alongside their financial targets and are independently audited every three years to ensure they stick to these goals.

To have the most impact you need to be highly profitable.

“I want to show that it is not all bullshit, that it is not just the product that is good but also how we do it, that we are not having bad management or polluting around the factories,” Hubert says.

Having said that, Hubert has no shortage of killer commercial instincts. I ask him when, if ever, he would consider selling Ynsect, and his answer is instant and somewhat vehement:

“I have no intention to sell it now, and not in the close future. At some point we might go for an IPO.” Hubert says timings for any listing would depend on what the market will be like in two or three years’ time.

Commercial ambition and environmental idealism are entirely interlinked for the ex-activist now.

“To have the most impact you need to be highly profitable,” he says.