When Sam Watson Jones returned to Shropshire, a rural county in the UK, to take over the running of his family’s farm in 2011, he could see straight away that it wasn’t working as a business. Watson Jones, the fourth generation to work the family farm, had previously been a management consultant in London and knew his way around a spreadsheet. The farm accounts did not make business sense.

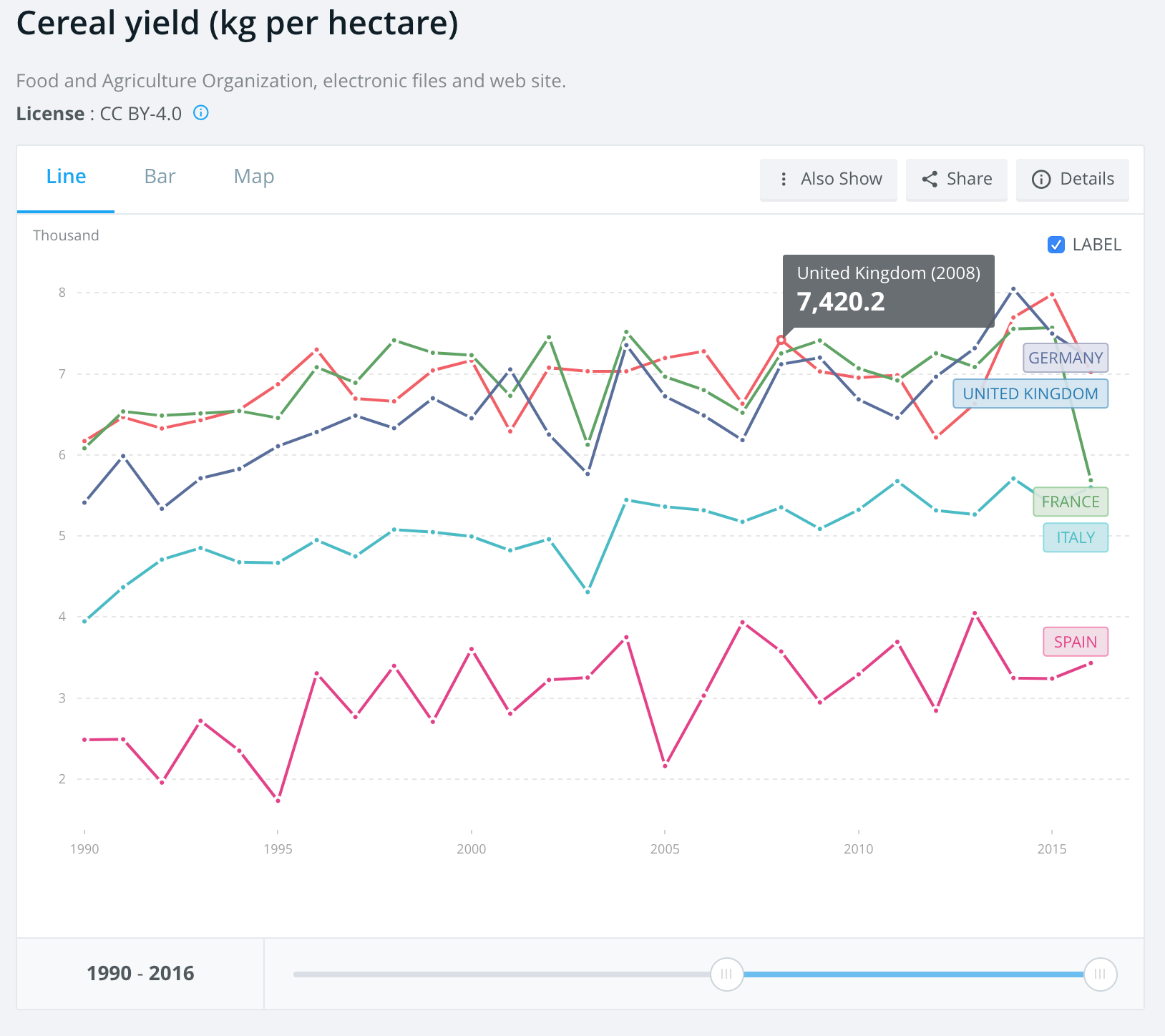

“I could instantly see what we were doing was ludicrous. It just didn’t stack up. The yields we were getting per hectare and the farm revenues hadn’t gone up for 20 years. They were the same as they had been in 1990. Meanwhile the cost of everything else had gone up,” he says.

Most of the neighbouring farmers said the same thing. Margins had been shrinking every year. Indeed, records from the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation show that cereal yields per hectare have remained largely static in the UK and other big European countries.

Some might have simply sold up, shaking their heads about low commodity prices and a disappearing rural way of life. Instead, Watson Jones began dreaming about robots.

“I was thinking about small, smart machines doing things more accurately, robots that could monitor the health and nutrient status of each plant in the field.” He felt it could be a way to increase crop yields, getting more value from each acre of land.

He couldn’t find any suitable bots, though. Nothing small or cheap enough seemed to exist, so Watson Jones teamed up with Ben Scott-Robinson and PhD students at the University of Bristol to start developing their own small machine.

In many ways the project started at just the right time. With the cost of computer hardware component decreasing, and a dramatic improvement in technologies such as AI and computer vision, it was just becoming possible to create a robot at relatively low cost.

The first prototypes were built with bits of kit bought on eBay. It was the start of Small Robot Company, one of a growing number of agrobot startups that are springing up to change the economics of farming.

Small Robot Company is creating a series of bots - called Tom, Dick and Harry - that can perform the various aspects of farm labour. Tom surveys the field and creates a digital map of plants, soil and other conditions. Dick deals with weeds - either by precision spraying or zapping them with electricity (Small Robot Company is working with another UK agrotech startup, Rootwave, on this part). Spider-shaped Harry, unveiled in November 2018, can plant seeds. All three types of robots are controlled by an artificial intelligence system called Wilma.

Development is still at an early stage, with trials being carried out at 20 farms across the UK, including the National Trust’s Wimpole Estate in Cambridgeshire and on farms run by Waitrose, the UK supermarket company. Only Tom and Wilma so far are functional, with Dick and Harry under development.

So far the company has been funded by grants from Innovate UK, the public sector funding body, but it has just raised a £1m funding round through Crowdcube that will help build the next set of robots.

Interest in agrobots is growing among investors. Last year, EcoRobotix, a Swiss startup developing a weeding robot, raised a €9m series-B round from investors led by CapAgro and BASF Ventures. CapAgro has also invested in Naio Technologies, a French weeding robot maker, which has so far raised €3.5m.

A solution to labour shortages?

Acute labour shortages on farms have been one of the drivers for developing farming robots.

“There is not enough labour. It doesn’t even matter if you pay more, these are not jobs that people are eager to do,” says Juan Bravo, founder of Agrobot, a Spanish startup developing strawberry-picking robots. “You can only get immigrants but as the economies in their home countries improve they are no longer willing to come over. We are seeing this in California with fewer Mexican pickers. In Britain after Brexit it could get very tough too.”

Strawberries are one of the most labour-intensive crops to pick - berries ripen at different times and must be handled delicately in order not to bruise the fruit. This may be why there are some 20 startups currently looking to develop strawberry picker bots.

Bravo began to tinker with a picking bot in his own garage in 2008, but he says, only in the last few years have advances in AI allowed him to turn a hobby into a serious business. Agrobot uses Nvidia’s Jetson AI chip to help it “see” each strawberry and recognise when it is ready to pick. Agrobot then spends months teaching and tuning the system to work with different varieties, different times of the day, in varying light and weather.

Around 6-7 seconds is the ideal picking speed for each strawberry.

Agrobot’s other unique selling point is created a machine with a large number of robotic arms - up to 30 - to do the picking. Strawberry picking is notoriously difficult to speed up - pick too fast and the fruit drops or bruises. Around 6-7 seconds is the ideal picking speed for each strawberry, says Bravo. To pick a crop faster, you need more arms working at the same time.

Bravo estimates that Agrobot would eventually be able to harvest up to 80% of a farmer’s strawberry crop autonomously. The final 20% - berries that are hard to detect - are likely to need human pickers.

The company has so far raised $2m, but is looking for further investment. Although most of the 10-person development team is based in Spain, Bravo has himself relocated to California, in part to find investors and also to be closer to the US state’s huge concentration of strawberry growers.

A more eco-friendly way to farm?

Agrobot builders are also hoping they will be a more ecological option. Ploughing and planting fields with heavy tractors causes great damage to the soil, making it vulnerable to erosion.

Much of the UK’s farmland, Watson Jones, says is being blown away by the wind. He remembers an old local farmer remarking how the field outside his house was now 18 inches lower than it had been decades ago.

“It was just an offhand remark, but it struck me that the farm was literally disappearing. And the reason it was disappearing was because of the machinery used on it,” he says. The UK loses around 2.2m tonnes of topsoil each year because of erosion according to estimates by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

A group of smaller, lighter bots would in theory do less damage to the soil. They would also allow farmers to decrease the use of chemicals such as fertiliser and pesticides, if these could be applied with greater precision.

“Farmers typically look at the weeds that are present and then apply a chemical to the whole field to kill them. Robots could apply them to just the areas where they are needed,” Watson Jones says.

Because many of the agrobot projects are still in a prototype or pilot phase, the business models for these startups are not clear. Small Robot Company is considering a leasing model allowing farmers to pay for use of the technology on a per-hectare basis. This would help make the technology more accessible for smaller farmers who would struggle to make a big, up-front investment in machinery. Agrobot’s Bravo, on the other hand, would prefer straight sales of machines to avoid the hassle and administrative work involved in a leasing programme.

Both are coy about mentioning any actual pricing yet, especially as a lot of work still needs to be done. Tom is still a little bit slow, and Watson Jones is only five months into a three year project to teach the machine learning software to recognise various wheat conditions and diseases. In fact, some agrobot companies are still to stay underneath the radar in this early development phase. EcoRobotix, for example, declined to speak to Sifted about its development work saying it wanted to stay out of the limelight for now.

Farming is the last great analogue industry.

But Watson Jones is convinced this is the start of a new era for farming. “Farming is the last great analogue industry. But if we could digitise it we could do things in a completely different way. We could have a per-plant understanding of the field and a per-meter understanding of the soil. Instead of farming in a way that works best for the tractor, we can farm in a way that is optimal for each plant.”

If we are to feed a growing world population, he adds, we will need to look at solutions like this. The Food and Agriculture Organisations (FAO) estimates we will need to increase food production by 70% by 2050 to feed everyone. “But the yield of some crops is no longer increasing globally year-on-year and the amount of land we have available is not increasing. So we need to change the productivity of the land,” Watson Jones says. “That is the big hairy problem we need to solve.”

Image credit: Small Robot Company