America is a dream expansion market for many of Europe’s startups — but as Sifted has reported in the past, there’s more to it than just upping sticks and moving stateside.

You need the expertise required to recruit well, there’s the pressure of choosing the right location for your HQ and then the financial risks of the bet falling flat.

You also need to knuckle down and — as dry as it might be — get through the admin, of which there’s a lot.

One of the trickiest elements is getting your head around the business of sales and use tax. With tax laws and regulations changing from state to state, startups need to be wise to the differences before planning expansion.

“It’s easy to see the dollar signs, but it’s so difficult to get right,” Veeraje Bhonsle, investor at JamJar Investments, tells Sifted on our latest Sifted Talks.

The panel also included:

- Larry Mellon, tax director, Vertex;

- Emmie Nygard, partner, EY;

- Hal Oral, finance director US, Babbel.

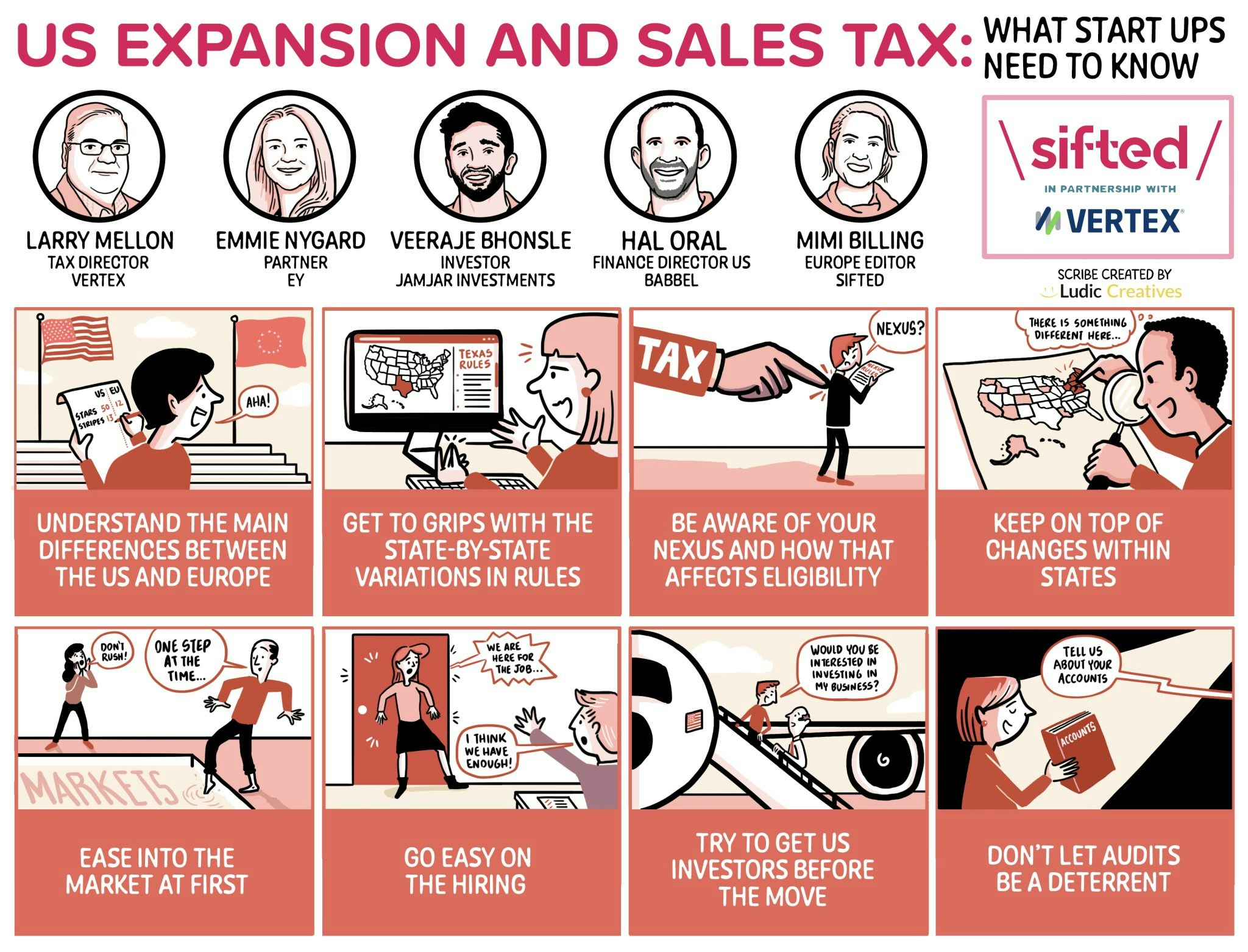

Here’s what we learned:

So, how can teams prime themselves to navigate the tax regulations of the USA and make expansion a success?

Understand the differences between the US and Europe

On a basic level, sales and use tax in the US works very differently from the systems used in Europe. Rather than VAT that is added at every stage of production, most US states have a sales and use tax that is applied just once to the final consumer on products that meet certain requirements.

“You sell a [product] for $10 and you get $10, but the customer pays the sales tax on top of that,” explains Oral.

There are exceptions — states like Alaska and Delaware don’t have a state sales tax, and choose to subsidise costs through other forms of tax instead.

Another major difference between the US and Europe is that there is no federal, countrywide sales and use tax.

“It’s 50 different countries rolled into one,” says Bhonsle — every state imposes its own tax thresholds and percentages, and each local jurisdiction within that state may have additional rules on top of that.

It’s 50 different countries rolled into one,” — Veeraje Bhonsle, investor at JamJar Investments.

Be aware of your nexus

A nexus is a company’s tie to a state, says Nygard — and it’s important to understand because it affects where and how sales tax is paid.

Your tie to a state doesn’t just include having a physical presence there. Alongside opening up a brick-and-mortar space, a nexus can also be determined through time spent at a conference or a sales or marketing team travelling out to a state for a couple of months, says Mellon.

Once you’ve “created a physical presence” in a state, you “have to register to collect [tax] and remit for the sales that you make in that jurisdiction,” he adds.

There’s also a financial nexus, where a company sells into a state without physically being there. In both situations, companies have to collect sales tax according to the rates set by the jurisdiction they’ve sold into.

But that’s not the only complication, says Oral: “It depends on what you are selling. Certain products are taxable in certain states and non-taxable in others. So, startups should check if the rules apply to their business or get the advice of a consultant to make things easier.”

Once you’ve “created a physical presence” in a state, you “have to register to collect [tax] and remit for the sales that you make in that jurisdiction,” — Larry Mellon, Tax Director, Vertex.

Keep on top of the changes

Not only do states differ in their tax expectations, but the rules are also subject to change — and often do.

Mellon says that in 2023, Vertex tracked 154 new districts set up in the US, where jurisdictions introduced a novel or changed tax to pay for a governmental or public expense. “You have to determine, ‘am I located in one of these areas, and did I meet the threshold?’” he says.

“It’s important to have a tax expert here in the US or a consultant to help you with these issues,” adds Oral. Not only will they assist companies with staying abreast of changes, but they can also help with gathering the documents needed in case the state later requests an audit, Oral explains.

“We will see states change [the rules] very quickly for very specific periods of time,” said Nygard, and “if you're sitting in Europe trying to manage that in the US, that will be very difficult”.

We will see states change [the rules] very quickly for very specific periods of time," — Emmie Nygard, Partner, EY.

Ease into the market

Rather than jump in feet first, both Oral and Bhonsle suggested that easing into the transition is a safer bet. “Once you’ve figured out where to go, we prefer trying new marketing campaigns on a small group [and] really testing and iterating on that cohort before expanding at scale,” says Bhonsle.

There’s also the option of using a third-party vendor to sell products, says Oral, which gives companies the chance to access the market without setting up or hiring in the country.

“It really depends on how much control you want,” he says, as setting up an entity means founders retain control over the marketing and sales strategy. But he adds, “If there’s a vendor who has success driving a product like yours before in the United States, that could absolutely be a more cost effective way to move in [...] rather than jumping in, creating a company and hiring.”

Go easy on the hiring

That also extends to your recruitment strategy.

Oral recommended that founders recognise what job functions they actually need to hire new people for.

“Maybe you just need a salesman or a marketing team in the United States. So it’s really identifying, ‘what are my absolute needs in the US to expand there?’ and just do that, you don’t need to replicate everything you are doing in your home country,” he says.

You don’t need to replicate everything you are doing in your home country," — Hal Oral, Finance Director US, Babbel.

Try to get US investors before the move

It’s ideal for companies to get a US-based investor on board before the expansion, says Bhonsle — though he acknowledged that it’s easier said than done. “Any expertise or local know-how you can get on board early on is incredibly helpful [and] given how expensive a market this is to crack, cash is always helpful,” he says.

There are a few ways to make the investment case stronger, he said: “Start small and really prove that there is consumer demand, prove there’s a clear-cut strategy to do this and then approach VCs once these two things are really nailed down.”

Don’t let audits be a deterrent

“The fear of the audit shouldn’t stop you from entering the United States,” says Oral.

While companies can be audited if it's suspected that they owe an unpaid tax, founders won’t be thrown out of the country if a mistake is made, adds Mellon.

“Under that audit period, which in most US states is a three or four-year period, [the state] would understand and assess that tax and you then would certainly go back and change your decision on how you tax those sales and purchases,” he says “You’re not being kicked out, you just pay the tax and a penalty for not doing it accurately — and then they’ll come back in three or four years to make sure you’re still doing it right.”

You’re not being kicked out, you just pay the tax and a penalty for not doing it accurately — and then they’ll come back in three or four years to make sure you’re still doing it right," — Mellon.

Like this and want more? Watch the full Sifted Talks here: