The rise of online delivery firms has been great news for some small restaurants and takeaway joints. Just Eat, Deliveroo, Wolt and co. have put them in touch with far more customers than they could have served independently — and their profits have grown as a result.

But the rise of many competing delivery channels has also caused chaos in the kitchen.

Most restaurants work with several delivery companies, each of which provides its own tablet and ordering system. Some still use pen and paper for in-house orders.

“Imagine a busy shift, customers are pouring into the restaurant, and there are three or four tablets going bonkers with orders coming in. The front-of-staff are bombarded with customers in front of them, taking orders from tablets and rekeying those orders into the EPOS [electronic point-of-sale] system — because that’s how to communicate with the kitchen.”

That’s the challenge as seen by Zhong Xu, founder of Deliverect, a Ghent-based software startup which brings all these channels and processes together into one management system.

Deliverect, which was founded in September 2018, integrates with most of the major delivery players in Europe, including Takeaway.com, Deliveroo, Uber Eats, Glovo, Delivery Hero and Just Eat. Xu says the company is signing up 100-150 locations per month to its subscription service, in Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Spain, the UK and Ireland. The company plans to move into the US and Asia in the future.

Mistakes are common with manual processes, Xu adds: he says Deliverect's customers report that one out of 15 orders were keyed in incorrectly before implementing its software. That can lead to problems with stock management and accounting.

Keeping menus up-to-date when they are shared across numerous platforms and websites is another challenge that Deliverect can overcome. “If you want to change a burger, you need to update it 100 times,” says Xu. “We automate that.”

Dark kitchen drama

It is even more chaotic in dark kitchens, the preparation-only sites which are springing up to cater for delivery across Europe.

Just imagine — it’s like a game of whack-a-mole if it’s not automated.

Dark kitchens often house several brands in one portacabin-like location. For eight brands, working with three delivery channels, there might be 24 tablets to keep an eye on. “Just imagine — it’s like a game of whack-a-mole if it’s not automated,” says Xu.

Deliverect works with Keatz, one of several European dark kitchen startups, which is developing its own delivery-only brands. Xu thinks that as more dark kitchen sites open up around the world, we’ll start seeing new food brands — like those being created by Berlin-based Keatz and its Paris-based competitor Taster — expand abroad more quickly.

“In Europe, a lot of [restaurant] brands are very local; they’re not established in different countries,” he points out. Dark kitchens could change that, and make it far easier (and less costly) to hop across borders.

Fears of market monopoly

While working with multiple delivery firms might seem like a hassle, it’s in small restaurants’ best interests to see healthy competition in the market, says Xu: “For a restaurant, it’s good to have multiple players. A lot of restaurant owners worry about a time where there will be market consolidation.”

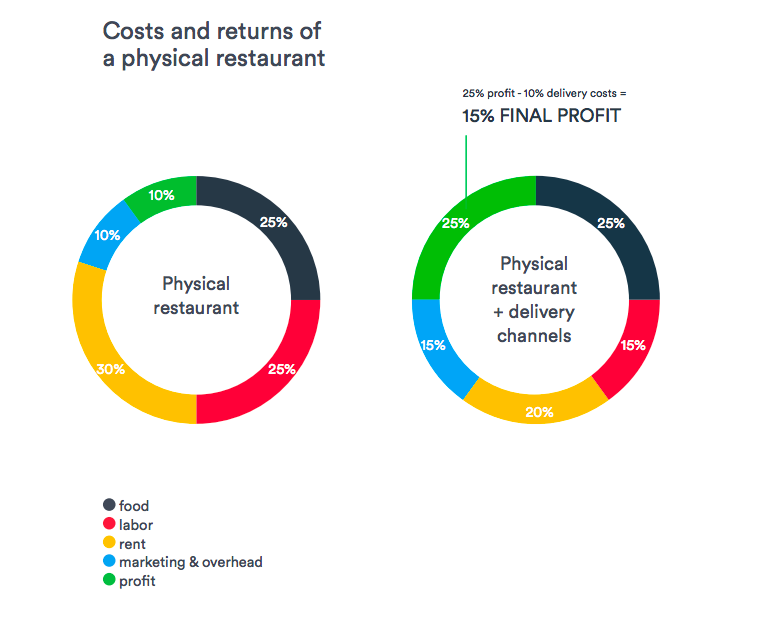

Delivery operators with a market monopoly (as Takeaway.com now has in Germany, following Deliveroo’s withdrawal from the country) could raise the commission they charge restaurants at whim. At the moment, commission hovers around 25-30% in most markets.

“It’s quite hefty,” says Xu — but worth it, he thinks. “Restaurants have fixed front-of-house costs: rent and people. If you don’t do delivery, or you do, you still have that fixed cost. The variable cost is food, so profit-wise, it’s ideal for restaurants to add delivery channels.” Among Deliverect's customers in the fast-casual dining market, 20-30% of total revenue now comes from delivery.