“Urgh. I can’t. I’d have to close my eyes,” says a woman inching backwards from a bowl of pasta topped with mealworms. Edible insects is not everyone's cup of tea.

In this particular instance, it's Jimini's, the French edible insect company, giving out free tasters at the fringes of Hello Tomorrow technology conference. But they're finding some people tough to convert. Granola containing ground-up mealworm powder (with no insect parts visible) goes down OK, but dried mealworms are proving a step too far.

Edible insect companies are trying hard to move out of the novelty fringe and into the mainstream. They are getting some traction — at the end of last year, for example, Sainsbury’s became the first UK supermarket chain to start stocking edible insect snack-packs in its stores, after agreeing a supply deal with UK-based Eat Grub, while Jimini’s products are on sale in French retailer Carrefour’s stores in Spain, and in Kaufland, Germany’s second largest retail chain.

Poppy Reid, marketing executive at Eat Grub, says the Sainsbury’s deal has provided “a dose of rocket fuel” for the brand, which previously had to sell mainly through its website and pop-up events.

Meanwhile companies that are growing insects for animal feed have seen huge investment rounds in the last few years. Ÿnsect, based in France, for example, raised $125m in a series-C round in February.

Edible insects need to get over the “yuck factor"

Ever since a United Nations report in 2013 noted that eating insects could be a greener way to feed the world — crickets for example need 12 times less feed than cattle to produce the same amount of protein — the idea of entomophagy (eating insects) has been gaining traction.

There are around 2,100 edible insects and around 2bn people already supplement their diets with insects according to the UN.

But the big question is: can edible insects ever become part of the mainstream western diet?

Twenty years ago people in Europe found the idea of eating raw fish strange, but now it is everywhere.

Aurore Danthez, communications manager at Jimini’s, is positive it is just a matter of time. “It is like sushi,” she says. “Twenty or thirty years ago people in Europe found the idea of eating raw fish strange, but now it is everywhere.”

Arnold Van Huis, professor of tropical entomology at Wageningen University and one of the authors of the UN report, says he is already seeing attitudes changing to edible insects and eating them:

“When I started my research noone in the Netherlands knew you could eat insects. Now everyone knows about it. When I do talks on this and ask how many people have eaten insects about half the hands go up. It has taken about 20 to 25 years, but we are making progress.”

But Jonas House, lecturer in the sociology of consumption at Wageningen University, who is researching the acceptance of insects as food, is more sceptical. He says most insects eaten by people at the moment are novelties and snacks. Moving beyond this may be hard.

“If an unusual ingredient is going to become popular it has to be part of a cuisine or cooking practice. It needs to be prominently part of that, rather than hidden,” he says. Hiding ground-up mealworms or crickets in burgers such as those made by German company Bugfoundation, may make them more palatable, but will not ultimately help popularise the idea of eating insects.

“At the moment it is difficult to say that this tastes better than that, when it comes to insects,” House says. “You need to find a dish where the taste of the insect is an integral part of the dish.”

Mexico’s Oaxacan cuisine, which features fried chapulines, or grasshoppers, is one contender for helping popularise insect-eating, and a handful of restaurants have popped up in cities like London. But one of the problems, House says, is that Mexican food is already heavily associated with a taco/enchilada/burrito repertoire, and so it may be difficult to turn it into a vehicle to push edible insects.

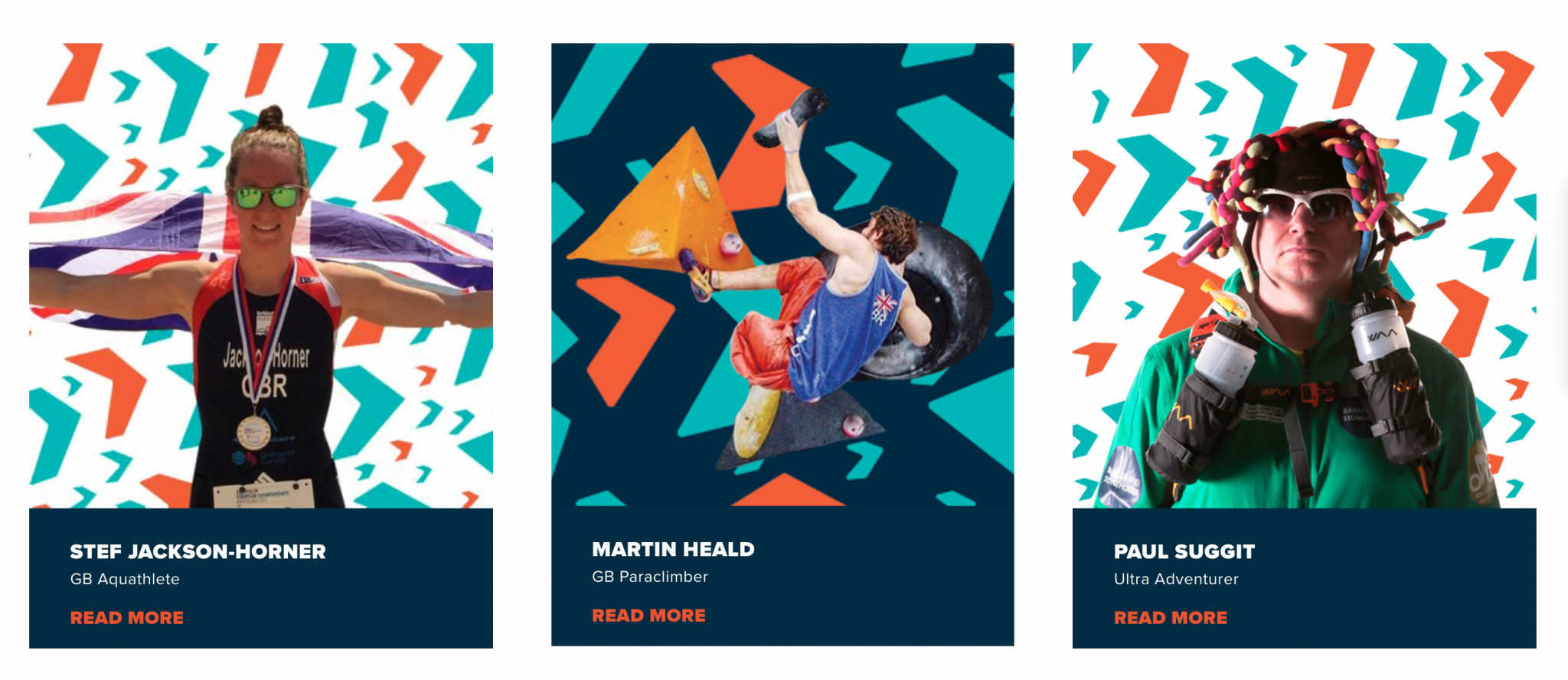

There are 10 or so edible insects cookbooks currently listed on Amazon but taste has not been a major selling point in many entomophagy discussions. Many of the companies selling edible insects tend to emphasise health or environmental benefits. Eat Grub, for example, features a whole page of brand ambassadors, most of whom are into extreme sports and like the insect-based products for their concentrated protein kick.

Novelty and environmentalism were some of the reasons people in the Reddit Entomophagy group gave for trying insects for the first time. That may not be enough for a mass movement.

- Read more: EU farming subsidies – for insects

Are edible insects too expensive?

The other problem with edible insects is the economics. Insects are still expensive to farm and struggle to compete with other food sources. This matters particularly when it comes to using insects for animal feed. While human consumers may be happy to pay over the odds for a novelty bag of spiced crickets, the animal feed market is cut-throat.

Insects must come at least close to competing on price with other types of feed. This is easier with something like fishmeal, which costs around $1500 a tonne but more difficult when it comes to soya beans around $400 a tonne. Sifted understands that the cost of insect-based feed is at the moment far off both of these.

Many of the big VC funding rounds that have gone into companies such as Ÿnsect and Protix are about developing automated facilities where insects can be grown at lower cost and with fewer staff.

Netherlands-based Protix, which farms the black soldier fly, raised $50.5m in 2017 and has used most of the funding to build a second, state-of-the-art insect protein facility near the Belgian border, with 15,000 square meters of production space and a staff of 110.

This is no longer a few people growing a handful of larvae.

“This is no longer a few people growing a handful of larvae. This is a full production facility,” says Kees Aarts, co-founder and chief executive of Protix.

Much of the $125m funding Ÿnsect’s raised in February will go towards scaling up a highly-automated facility in France.

Antoine Hubert, Ÿnsect’s founder and chief executive, says it will produce mealworms using techniques similar to those seen in indoor vertical farming, with the mealworms rotated around various optimised growing environments before meeting their end by being steamed, much like shrimp are. The company has around 25 patents covering all aspects of its production techniques.

Hubert says Ÿnsect’s intention is to take a part of the $500bn animal feed market, especially as fish meal grows more scarce due to depletion of fish stocks.

Nevertheless, Ÿnsect’s market at the moment is mainly hypoallergenic dog food — partly that is to do with regulation (see below) but also because pampered pets are an area where the cost of the product is less of a consideration.

Cutting the red tape

Making insect farming economical also means getting rid of unhelpful regulation. The European Union allowed human consumption of 10 species of insect in 2015, under the novel foods regulation. But insects as animal feed has been trickier.

Bizarrely, while it is legal for humans to eat insects, they cannot be fed to chickens or pigs.

All animal protein was banned from animal feed following the BSE, or mad cow disease, crisis of the late 1980s and early 90s, and this included insects.

Bizarrely, this means that while it is legal for humans to eat insects, they cannot be fed to chickens or pigs. And while a chicken may gobble up a live bug it comes across in the barnyard, it cannot be given dried ones by a farmer.

The insect industry has been lobbying for change, however, and insects can now be used for fish feed, with changes to laws regarding chickens, pigs and ruminants expected to follow. The restrictions on eating insects have not applied to pets, which is why the hypoallergenic pet food market is a good one to start in.

Looking for the right way to present it

Following the spate of big investments, insect farming is now poised to go from pilot stage to full industrial production.

And while Ÿnsect is focused on just the animal feed market, Aarts says Protix’s target market is “every living creature on the planet — man, animal and pet”.

“We just need to develop an appealing proposition,” he says.

One project that excites him is the Oer-egg, high quality hens eggs produced by chickens that are fed a more natural “primordial” diet of live insects. Because the chickens are eating live rather than dead bugs, the EU feed ban does not apply. And the eggs, sold in the Albert Heijn supermarkets in the Netherlands at a price of €1.99 for six, can command a premium but still be competitive with regular organic eggs.

Insect-fed eggs could be a great halfway house to getting people to eat the insects themselves, and Aarts is willing to be patient.

“It may seem like a slow market when you compare it to some pizza delivery app that can become a unicorn in a year,” he says. “But those startups aren’t bringing such a massive shift in ingredients and human health.”

European edible insect companies and funding

- Eat Grub (UK) raised $250,000 in 2016

- Jimini's (France) raised $1m in 2017

- Ihou (France) raised $900,000 in 2017

- Bugfoundation (Germany) raised an undisclosed strategic investment from PHW Gruppe in 2018

- Entis (Finland) raised a $200,000 seed round in 2018

- Enorm (Denmark) $2.4m grant from the Danish Ministry of Food and Environment in 2018

Insect production company funding rounds

- Protix (Netherlands) raised $50.5m in 2017

- Enterra Feed (Canada) raised an undisclosed amount in 2018

- AgriProtein (South Africa) raised $105m in June 2018

- Innovafeed (France) raised $40m in December 2018

- Hargol (Israel) has raised $2.5m to date

- Ynsect (France) - raised $125m in February 2019