When VC firm EQT Life Sciences launched its first fund focused specifically on dementia startups in 2020, it was not a crowded space.

“People believed [it] was a graveyard,” says EQT partner Philip Scheltens.

But four years on, that’s changed.

An increasingly ageing global population means that diseases like dementia, Alzheimer’s and motor neuron disease are on the rise. Alzheimer’s Disease International predicts that 78m people globally will suffer from dementia by 2030, up from 55m in 2020.

After 20 years of no new treatments, two new drugs for Alzheimer’s emerged in 2023. Japanese company Eisai’s drug Lecanemab received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US, and it has applied for regulatory approval in the UK. US-based Eli Lilly’s drug Donanemab is awaiting an FDA decision this year.

The new drugs and regulatory response have offered a confidence boost to the viability of the neurodegenerative space. Investors Sifted spoke to say this has shifted VC attention towards startups in the sector, with funding going into everything from novel drugs to methods to make treating the brain easier and more effective.

The market potential

The two new drug developments are just the beginning, says Laurence Barker, partner at the Dementia Discovery Fund (DDF):

“[It is] enormously encouraging for the industry, for patients and for everyone working in this sector — but it does remind us that the remaining unmet medical need and opportunity is enormous,” he says.

Barker says that several companies within the DDF’s portfolio, which all focus on neurodegenerative diseases, have seen increased interest from biotechnology investors. “We are seeing more entrepreneurs looking to take really exciting science and look to build companies and spin them out — and that's because the science is maturing in its own right,” he says. “The deal flow we are privy to just gets better and better, more mature, more insightful and more exciting.”

Scheltens adds that the direction of money in biotech has shifted too. While oncology still takes a good chunk of biotech funding — almost a quarter across 2023, according to Dealroom data — he says VCs are increasingly looking to expand their portfolios beyond cancer and are starting to consider diverting some of that investment into the neurodegenerative space instead. The potential returns are also huge; the market is predicted to be valued at $92bn by 2032.

Barriers in the brain

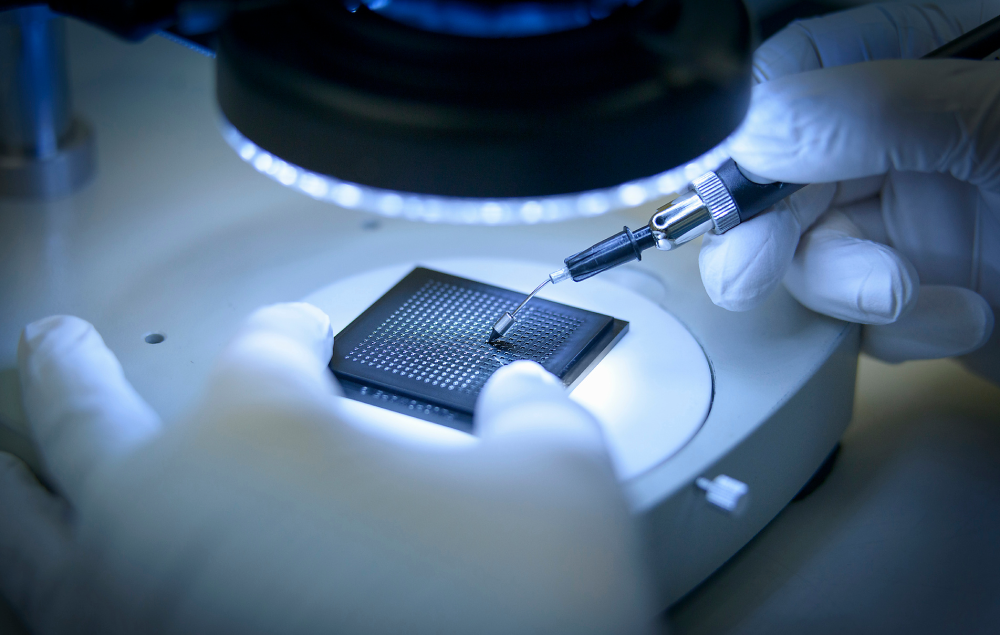

Startups in Europe are attacking neurodegenerative diseases in multiple ways. One of them, Lyon-based Carthera, is developing a wearable ultrasound device that sits on an outer membrane on the surface of the brain and temporarily opens up the blood-brain barrier to allow drug molecules to pass through it.

Dr Tim Viney, a career development fellow in the University of Oxford’s Department of Pharmacology, says that breaching this barrier — which stops drugs reaching cells — is one of the main issues for treating the diseases. For drugs like Lecanemab and Donanemab to be effective, they’ve got to cross this barrier, he says.

Carthera is currently focusing on fatal brain tumour treatments — it’s testing whether its device could safely open the blood-brain barrier to allow cancer therapies to reach tumours more easily and more effectively than is currently possible.

It has its sights on neurodegenerative diseases next and has a trial for Alzheimer’s in progress — in 2022, it ran a pilot study with nine patients that the research team found to be “safe and well-tolerated”. Its CEO, Frédéric Sottilini, says the company is also working towards starting trials in the motor neuron disease ALS.

For many neurodegenerative diseases, we can’t accurately identify the hallmarks of the disease because we haven't been able to link complex variations in neural data to the root causes of the diseases

In December 2023, Carthera closed a €42m Series B from investors including Supernova Invest, Bouscas Med and US-based Unorthodox Ventures. Sottilini says that despite a challenging fundraising environment across European tech, the raise wasn’t much different to the company’s previous round in 2022.

Another startup, BIOS Health, is trying to rectify the lack of data on how brain signals react to treatments, which CEO and cofounder Emil Hewage says is also holding back progress.

“For many neurodegenerative diseases, we can’t accurately identify the hallmarks of the disease because we haven't been able to link complex variations in neural data to the root causes of the diseases,” he says. That means there’s currently a lot of guesswork involved when testing treatments.

BIOS is mapping nerve signals to identify their links to major diseases — which can then be used by companies developing treatments to measure how those treatments affect the neural system and if they’re targeting the right neurons for each disease. In June 2023, the company raised $20m from XTX Ventures, Selvedge Venture and Mark Slack, the founder of medical robotics company CMR Surgical.

The US is a focus for both BIOS and Carthera. The latter reopened its Series B round to bring a US investor on board — Sottilini says that with a goal of regulatory approval in both European and American markets, it was important for the company to have someone on the ground to help navigate operations in the States.

For BIOS, the US presents a huge market opportunity. “Spending on clinical trials is in the process of doubling over this decade, and the US market is ultimately the home for many of the medicines that are being trialled,” says Hewage. He adds that there’s currently more than $20bn in order backlog for precision trials of neurological therapies, most of which are based in the US — a backlog that BIOS hopes to address by setting up its own clinic in the US designed for this need.

Other startups in the space have caught investor interest: University College London spinout AstronauTx, which is developing a series of small molecule therapies to treat neurodegenerative diseases, raised £48m led by Novartis Venture Fund, the venture arm of the pharma giant. Other investors included the DDF, US-based MPM Capital and Australian VC Brandon Capital Partners.

And in 2021, UK-based startup AviadoBio, which is developing gene therapies to stop the progression of diseases like dementia, raised an $80m Series A from New Enterprise Associates and Monograph Capital. In 2023, it moved into new lab spaces in London’s Canary Wharf and announced that it would be taking one of its treatments through to Phase 1/2 clinical studies.

What next?

Though new treatments receiving regulatory approval could boost the validity of startups working in the space, drugs approved by the FDA have come under scrutiny.

Lecanemab, the treatment the FDA approved last year, has a warning attached that it could cause “serious and life-threatening events” in rare cases after three patient deaths were potentially related to the drug. In 2021, the US regulator gave Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm, developed by Biogen and Eisei, fast-track approval — but the European Medicines Agency (EMA) refused to follow suit, citing concerns around the safety of the drug and conflicting trial results.

The timescale for startups to make it to market is also a concern for some investors.

When BIOS was fundraising, Hewage says that “investors became universally concerned with the reality of the timing of when techbio and deeptech companies like ours would start to make money”.

Viney adds that there are years of work behind recent progress in the space. “[These developments] just happened to culminate in the last two years, but come from decades of research since the 80s,” he says.

There’s no “quick win” when it comes to developing treatments that slow the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, says Scheltens, symptoms persist even when the disease has slowed. He wants to see more startups working on this issue. Progress here can be achieved quicker, he says, as the clinical trial timeline is shorter than in drug development studies — while novel drugs usually require 18-24 months worth of clinical trial studies, he says, symptomatic trials typically need around six months.