If you are a US university student, you will soon have the option of getting your takeaways delivered by robot thanks to the ambitious expansion plans of Estonian startup Starship.

Started in Estonia by ex-Skype entrepreneurs Ahti Heinla and Janus Friis, the company about to dramatically increase the number 6-wheeled delivery bots roaming the streets, following a $40m Series-A funding round.

While questions are being raised about the economics of such a robot delivery business, the company is unabashed.

Lex Bayer, chief executive, tells Sifted that the company, which is headquartered in San Francisco, plans to expand to 100 US university campuses over the next two years. With a typical fleet of robots being somewhere between 25 and 50, that could mean more than 5000 robots in service by 2021.

Starship has been testing the bots — which typically deliver takeaway meals and groceries — on American university campuses for some time, and says it has reached a point where it can start ramping up quickly.

“It took us 4 years to get to 10,000 deliveries, then 8 months to get to 50,000 deliveries and just four months to get to 100,000,” says Bayer. “We’ve had to solve a lot of problems over the last few years, but now in most places we just put the robots down and they start working.”

The biggest difficulty, Bayer says, has been putting together the different elements of running a robot delivery fleet. It is not just about building the hardware and software, but putting in all the systems and services needed in the background, from orchestrating the movements of the robot fleet across the city to teaching shops and restaurants how to use them, and having in place people to charge and clean the bots once they finish a shift.

“We have got to a point where the deliveries work seamlessly for the user, but no one realises all the things that have to happen in the background,” says Bayer.

Does the model make sense?

The economics of a robot delivery service still have some question marks, though.

One person is still needed to service every 10 to 20 bots. This can be anything from maintenance to remotely monitoring the vehicle, ready to take over if it encounters a problem.

The economics of robot deliveries depends on getting the bot to human ratio as high as possible, but there are currently limits to this, as most countries still require some kind of remote monitoring of the vehicles.

Then there is the cost of the hardware. One bot costs around $5500 — according to Kristjan Korjus, Starship’s Head of Data, at a London AI conference in 2018. Starship would like this to come down to $2250 eventually. With delivery charges priced at around $1-2 at the moment, each machine has to do a minimum of 2250 deliveries (that would be around 6 trips every day for a year) in order to start paying back, before any of the costs of the human service crew.

People really change their behaviour when they are offered delivery within the hour.

One big question is over how long the bots will last. One of the big problems of the scooter industry has been that the scooters often don’t last long enough to make a return.

Bayer says the bots can drive the equivalent distance of between the earth and the moon (that’s 384,400km in case you were wondering) over a year and still be fine. The company says the bots last a couple of years in service without needing major repairs.

The good news is that customers do seem willing to use the service frequently. Bayer says frequency surprised the team and partnering shops in Milton Keynes.

“People really change their behaviour when they are offered delivery within the hour. People do big weekly shops because it is a lot of trouble to drive to the grocery store, look for the food, queue to pay. They don’t want to do it more than once a week. But with this they might be cooking and realise they are out of olive oil and just order it to arrive within half an hour.”

Bayer says Starship hasn’t done a lot of experimentation with pricing yet, but people appear to be finding the current level of $1.99 in the US, or £1 in the UK, a fair exchange for saving half an hour of time in running a dull errand.

The legal side

One of the reasons the US rather than Europe is getting this big influx of delivery bots is down to the law.

The US has been quicker to pass laws to allow robots to drive on pavements. Starship hired the same team that lobbied for Segways to be allowed to drive on sidewalks and so far nine states, including Virginia, Washington DC, Washington state, Florida, Wisconsin, Texas, Idaho, Utah and Arizona, have given this the go-ahead.

Nine US states have given robots the green light to ride on pavements. In Europe the picture is mixed.

They haven’t won lawmakers over everywhere, however. San Francisco banned delivery bots from its pavements in 2017, although it has recently given another startup, Postmates, a permit to test its bots in the city.

In Europe the company hired Lembit Opik, the former British MP, as its director of public affairs, but progress has been slower. Autonomous pavement-riding bots have been given the legal green light in Finland and Estonia (of course), and an in handful of cities in the UK, including Milton Keynes. This is why one of Starship’s biggest European operation is in Milton Keynes.

But elsewhere the situation is murkier. In many countries, such as France and Germany, robots have to be accompanied by a human, which pretty much negates the original point of building an autonomous delivery vehicle.

Elsewhere in the sector, Paris-based TwinswHeel is testing robot deliveries on the streets of Paris with supermarket Franprix. But at the moment these are mainly being used to help elderly people carry their shopping, rather than going out completely on their own. TwinswHeel is lobbying for a change in the law.

Starship is making a case for the electric-powered bots as an eco-friendly option that takes cars off the road, and which can provide vital services for elderly and disabled users.

Bayer even argues that robots could be the saviours of local community businesses trying to battle against online competitors. “Suddenly you can get anything delivered within an hour from, for example, your local hardware store. It lets these companies compete with online businesses without having to build all that infrastructure themselves.”

The competition

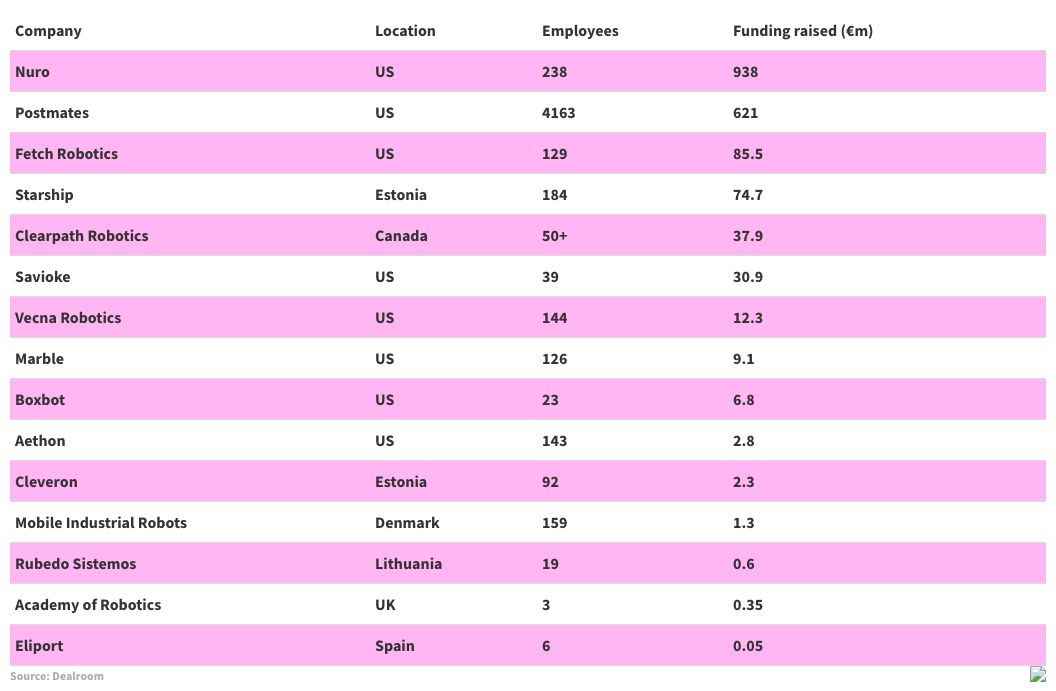

Starship is moving quickly in this area, but it does have a lot of competition.

There is not only Amazon’s Scout, which began field tests earlier this year, but a couple of big US rivals (and a bunch of smaller European ones).

There are also the more traditional competition from the human-powered delivery startups. , Heavily venture-backed companies such as Deliveroo and Takeaway.com are intensifying their competition across Europe for delivering meals and other items. Starship’s bots, which move at a speed of just 4 miles per hour, may not be able to compete against these car and bike couriers for speed. And, unlike humans, they can’t climb stairs (Dr Who fans will know that the same fatal flaw undid the Daleks).

In some cases Starship could work with the delivery companies. It ran a trial with Delivery Hero in Hamburg in 2017, for example, although it opted not to continue the collaboration.

Drone deliveries may be another competitor. Uber and companies such as Ireland’s Manna.aero are planning to launch services to deliver meals soon.

But Bayer says he is not too worried about the drones. “The problem with drones is that it takes a lot of energy to lift things, and it can be dangerous if they drop. Imagine a drone trying to deliver a 6-litre pack of bottled water, for example. Drones are also noisy and won’t always have the landing zones they need.”

“I love drones personally and I think there is a great market for services like Zipline which is delivering blood to parts of Rwanda with poor road infrastructure. But for deliveries in cities they have a lot of challenges.”