Infarm’s startup journey started out like many others: as an experiment.

Its Israeli cofounders Osnat Michaeli, Erez Galonska and his brother Guy Galonska, who had settled into a modest apartment in a multicultural, residential area of Berlin in 2012, had the bright idea to grow crops indoors using nutrient-packed water rather than soil. Their vision was to make cities more self-sufficient by bringing urban-dwellers fresh produce grown in farms on their doorsteps.

A few trips to a hardware store and hours of tinkering later, the trio had built a contraption. Yes, it was leaky. It was inefficient. But it would form the basis of the company they would later grow to over 1,000 employees across 10 countries — and raise nearly $500m for, scoring a $1bn price tag from investors.

Then the company went silent.

This year Infarm was declared insolvent in Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, and it exited Denmark and France. Its coriander, basil and sage have disappeared from Aldi in Germany and Marks and Spencer in the UK. Its flagship growing facility — the size of one and a half football pitches — in Bedford, England, has permanently closed. And the number of employees listed on LinkedIn has halved since December 2021.

Infarm declined to comment for this piece, and said it does not "comment on any rumours, speculations or opinions."

So, how does a $1bn company just disappear?

The vision

Hydroponics — growing plants without soil — isn’t a new idea. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are one of the first-ever cited examples of the technique from thousands of years ago, but the actual science was not greatly developed until the 20th century.

In recent years, hydroponics has gained attention as a way to reduce the environmental footprint of food production, which contributes a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The technique also makes it possible to bring farms to cities. 38% of land globally is used for agriculture; Infarm’s vertical farms could fit in a closet.

Or your local supermarket. Infarm installed its first vertical farm — a greenhouse-esque unit the size of a large wardrobe — in a Berlin-based supermarket, Metro Cash & Carry, in 2015.

An early pitch deck from the company states its indoor farms for retailers and restaurants were 57x “more efficient” than soil-based agriculture. Its units for wholesale and distribution centres — where individual units were stacked on top of each other to create huge farms — were touted as 420x more efficient.

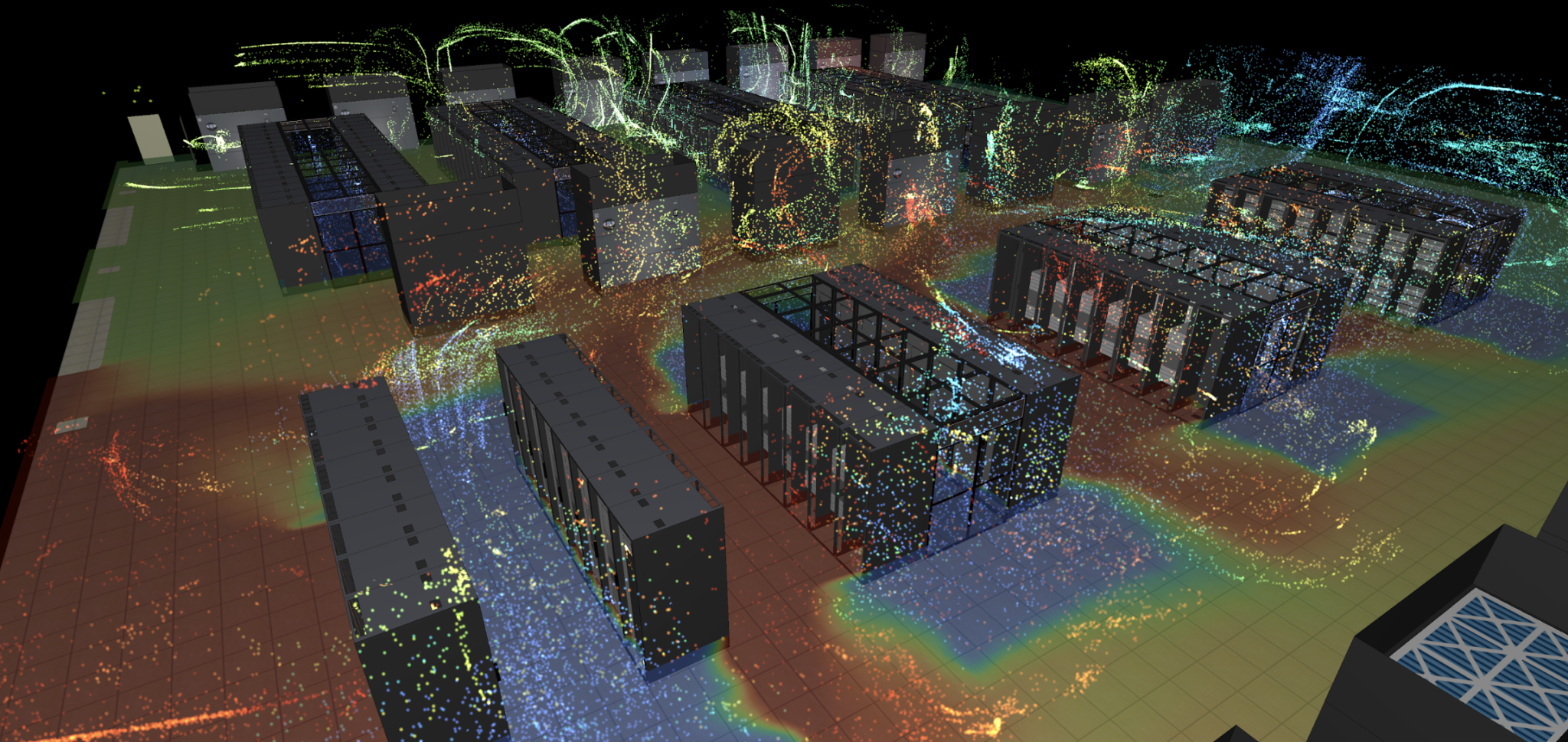

Infarm had something ancient Babylon’s gardeners did not: software. All of Infarm’s farms across the world were connected to a cloud-based control centre in Tempelhof, Berlin, which remotely monitored the plants’ nutrients, light and water usage to enable optimal conditions.

By 2021, Infarm’s farms yielded 75 different species of plants, according to its website, from Thai basil and coriander to cauliflower and strawberries. It had partnered up with over 30 major retailers including the German supermarkets Aldi Süd and Edeka, French wholesaler Carrefour, US-based Wholefoods, and it even had units in iconic UK department store Selfridges and IKEA.

It boasted 1,400 farms across Canada, the US, Japan, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the UK and Switzerland. And investors like Atomico and Balderton had valued the business at $1bn.

In the startup world, where 90% of companies fail, one’s ability to fundraise and sell a story to investors is the most important skill an entrepreneur can have, says one former employee. “The founders were exceptionally good at that."

"Buying something that didn’t exist"

The company’s seeming disappearance likely has roots in problems that started early on.

Three former employees, who joined Infarm in its infancy, describe the company as having a typical “startup mentality” — promising big things and figuring out how to do them as it went along.

“There was a huge buzz about us in the entire supermarket vertical,” says a former senior Infarm employee who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity. “We got a lot of attention from the media, all the big TV shows and newspapers were talking about us. Clients streamed in. But I think at that point, we weren't really ready for that.”

One of the company’s first major contracts was inked with Germany’s largest supermarket corporation, Edeka, in 2017.

“Edeka was kind of buying something that didn’t really exist. I mean, the ground structure was there, but not the extra features,” says a former senior employee, adding that this happened on multiple occasions with multiple stores. (Sifted has reached out to Edeka for comment.)

One new feature promised to customers before it had been proven by Infarm’s R&D team was strawberries. Senior leadership knew that simply selling herbs was not enough to help the startup turn a profit, so the founders decreed that strawberries, that “have a higher margin than basil”, should be grown from the indoor farms, the former senior employee says.

“That was always the Infarm style: the [leaders] did a bit of research, spoke to a few people, and got the plant scientists to start doing testing on strawberries — and sales were already selling farms [to customers] with strawberries,” they added.

“And [the R&D team] were like, 'we have no fucking clue about strawberries'. But they just signed a deal.”

The senior employee adds that the R&D team were often forced to “ship and install things that were not 100% ready,” inevitably leading to issues with the technology that were costly to fix.

For example, the expansion to Denmark was based on delivering a plant pot product — imagine a small plant of basil that you’d buy in a supermarket — of a specific height and weight that the local customers were accustomed to. The dimensions and weight were “technically impossible” for Infarm to produce in its machines, says an employee, a detail the leadership team only learned after the contract was signed.

Quite often, contracts were signed that placed the farms outside the “defined ranges” of where the plants could grow successfully: for example, in a basement with no internet or mobile connection, or in the frozen foods section of a shop where it was too cold to grow plants, they added.

This resulted in operational teams making far-reaching efforts “to accommodate each location with limited success, typically causing below standard plant quality and eventually the tech being removed and the contract cancelled,” the employee added.

Burning money

By 2021, Infarm was burning tens of millions of Euros a year, and it wasn’t bringing much money in either, the company’s filings show.

Infarm’s revenue was just €8m in 2021, up from €3.8m the previous year. Losses jumped from €74.6m in 2020 to €127.8m in 2021 as the company pursued expansion to Denmark and the UK, and the opening of its flagship growing centre in Bedford, England, ostensibly one of the largest in Europe.

By November 2022, with sales lagging, Infarm announced it would be laying off 500 employees, roughly half its workforce. At the time, the company blamed supply chain disruptions and soaring power costs made worse by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February.

Vertical farms often struggle to compete with traditional growers because the latter’s produce is often cheaper — in part because open-field agriculture or greenhouses have “sunlight for free” and “use little energy”, says Cindy van Rijswick, a global strategist for the fruit, vegetable and floriculture sectors at Dutch cooperative bank Rabobank.

An early Infarm employee says that electricity prices were never really a concern for the company’s leadership. “Some of the facilities figured out way too late, ‘oh we should probably be checking how much we’re paying for electricity per month.’ That’s pretty basic when 30-40% of the cost of the crop is electricity,” he says.

“Those things were just overlooked because investors will pay for it, it doesn’t matter,” he adds.

Aside from energy costs, pricing is also an issue for vertical farms. To make any money off their crops, vertical farms have to charge a premium, and it’s hard to convince consumers to pay a high price for lettuces grown indoors, says van Rijswick.

Then there are high people costs. Companies have to hire expensive researchers in order to roll out new products; Infarm had its own crop science department full of extremely qualified people with PhDs who came with a hefty price tag, say three former employees. Total personnel costs rose from €38m in 2020 to €77m in 2021, filings show.

Infarm isn’t the only vertical farming company to have struggled in Europe. There have already been several vertical farm casualties on the continent, including France’s Agricool, Israeli-Dutch group Future Crops and Glowfarms, based in the Netherlands.

Court cases and exiting markets

By 2023, Infarm had exited the majority of its European markets. The company departed from France, Denmark, the UK and the others one by one, and then seemingly disappeared from public view. Its once lively social media accounts have been dead since March of this year.

It wasn’t just Infarm itself that suffered from what employees describe as a slow and painful shutdown.

One former Berlin-based business partner of Infarm told Sifted that her contract with the company was abruptly terminated on December 1, 2022, and she waited three months for the company to respond to her requests for payment. It was only when she got the courts involved that Infarm agreed to pay her.

“They ignored all reminders from me personally for months,” she told Sifted. “It was pretty scary since it was a lot of money for my business.”

Court filings in the UK also show there were two cases against Infarm — one from a steel company, and one from an industrial spec builder, supposedly both suppliers of Infarm — for "breach of contract", one of which is still active. Both companies that filed the cases did not respond to Sifted’s requests for comment.

Will Infarm return?

This is where the evidence seems to stop for Infarm. People who once worked with the company are just as confused about how quickly it disappeared.

The company’s flagship growing centre in Bedford is marked permanently closed on Google, yet the local council in Bedford were unable to confirm whether the building is still owned by Infarm or has been sold on, nor where all the company’s farming equipment went.

Sifted also spoke to the office of the MP of Bedford, Mohammad Yasin, who cut the ribbon to the facility on its opening day. Even he doesn’t know what happened to the project.

But as Sifted started to try and figure out what exactly happened to Infarm, it became clear that this perhaps wasn’t as simple as another startup running out of cash and folding. There are signs that Infarm may be planning to try things again: the question is, what?

In the UK, Infarm registered two new entities with the three cofounders as directors in September: May DNU, which was originally registered as Infarm Technologies and changed its name a few days later, and May Acquisitions.

Two employees told Sifted that Infarm set up the UK entities to salvage the assets in the markets where they went bankrupt.

Another employee told Sifted that Infarm already sold a lot of its supermarket farms “for scraps” at the end of last year and has been trying to sell the rest of its equipment. The future plan, he says, is for Infarm to “restart” as a farming-as-a-service company in London, where Erez Galonska is now based.

“But I don’t know how they will do that, because a lot of the knowledge has already walked away or has been fired,” he adds.

Many of the employees Sifted spoke to also said that the company could have already sold a lot of its equipment to players in the Middle East with the hope of opening new facilities in the region.

Right now, the economics for vertical farming make the most sense in the Middle East, where extreme heat prevents the growing of crops in fields, food security is a pressing issue and energy in the region is cheaper, says Rabobank’s van Rijswickl, as well as former Infarm employees.

The region is currently throwing big money at vertical farming. The world’s largest vertical farm opened in Dubai last year.

Back in Berlin, where it all began, chatter can be heard from the courtyard where Infarm’s cafe in trendy Kreuzberg used to be. The plant-adorned eatery, which fed customers on lettuce grown a few steps away in Infarm’s growing centre, is now occupied by a storage facility for another cafe. Workers can be seen unpacking boxes onto shelves, grinding coffee and doing paperwork in their office. No plants of basil and sage hanging from the wall can be seen.

Erez Galonska once held weekly brunch meetings in the space, sharing his vision with the public about revolutionising food production forever with vertical farming. With murmurings of Infarm starting up again, will that dream ever be made a reality?

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify that the layoffs of 500 people occurred in November 2022, rather than in the summer.