Whether it’s the nasal spray you breathe in to keep hay fever at bay or a colleague’s perfume, products that can make their way into your lungs have to be rigorously tested before it’s considered safe for humans.

Currently, most of that pre-clinical testing — the early testing before clinical trials on humans — happens on animals like rats and pigs. But, alongside the ethical concerns of that method, the process is often a shot in the dark: a 2021 report by trade association Biotechnology Innovation Organisation (BIO) found that 92% of drugs that are tested on animals later fail in human clinical trials.

It’s also costly. A simple test on rabbits to see if a drug will cause a fever can cost $475, and extensively testing a cancer treatment on rats can put you $700k out of pocket.

In response, techbio startups are beginning to come up with solutions that could one day remove animals from the testing process. One of them, UK-based ImmuONE, is doing that by building a miniature model of the human lungs, aiming to reduce the number of products that are later tested on animals.

ImmuONE’s “cell in a dish”

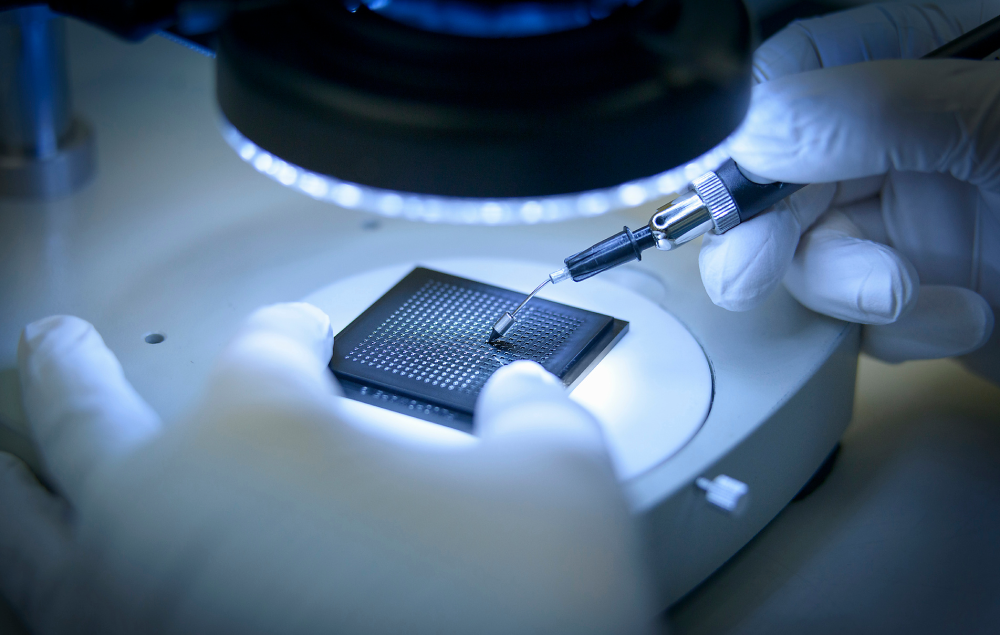

ImmuONE’s “cell in a dish” product is made up of a small flat tray with a set of mini test-tube-like wells — it kind of looks like a deep paint palette, or an inverted fidget popper toy.

Its purpose is to represent the lower airways of the human lungs, and in each well the company adds cell cultures combining human tissue and immune cells, which when testing is carried out replicate how these cells work together in the human body. The molecules of the product being tested are then added to each well to test how the lung and immune cells react.

The addition of immune cells means that testing reveals more granular detail than other methods, like whether lung cells’ response to an inhaled substance is reactive and harmless — like when dust makes you sneeze — or one that triggers the immune cells to attack, and is therefore potentially harmful.

ImmuONE sells its device to companies to carry out tests themselves, but also offers to do the testing for companies that want more advanced and detailed testing for a product but don’t have the experience to carry it out in-house. This service is where the bulk of the team’s focus currently lies.

The company was spun out of the UK’s University of Hertfordshire from research by Abigail Martin, who studied biotechnology at Ireland’s University of Galway before specialising with a master’s in toxicology, and then a PhD specifically in inhaled toxicology. Dr Victoria Hutter — an academic expert in in vitro modelling, which is cell experiments that happen outside of a living organism — supervised Martin’s PhD project, and became a cofounder when it spun out.

The complexities of regulation and the scientific knowledge required to understand the potential for this technology make for a difficult sales pitch. When she started having investor conversations in December last year, Martin found that the company was operating in a “very niche space”. Many investors are looking for the next big medicine, she says, and aren’t interested in the pre-clinical space — despite this being crucial to the development of new headline-making drugs.

While some generalist tech investors were interested, most of them admitted to Martin that they lacked the knowledge and expertise to handle the science. Instead, the company raised its £2m seed round in October this year from investors including healthtech VCs Mercia Asset Management and Pioneer Group.

So, could animal testing actually be replaced?

ImmuONE isn’t the only company building in the space in Europe. Several companies are working on organ-on-a-chip and organoids technology to offer an alternative to current testing methods. Zurich-based InSphero, which has raised around $42.3m since founding in 2009, has a 3D organ-on-a-chip product which simulates human liver cells for drug and therapeutics testing; UK-based Cellesce, which was acquired by US pharma MDS Analytical Technologies in 2022, offers bioprocessors and bioreactors to reproduce organoids (human cells that are clustered to mimic the functions of an organ) at scale for the drug discovery industry.

Martin says there's “an absolute possibility” of a future where this technology can replace animal testing, but there are several barriers in the way.

One is investor support. “The more [the sector] becomes established and financially supported, the faster we're going to see those advancements,” Martin says.

There’s also the small issue of regulation, which means a reality where animal testing is entirely eradicated is still a way off. Current regulation across the globe around the safety testing of drugs and cosmetic products still require animal models.

We are in an era where technologies such as ImmuONE's and its applications will eventually be able to replace animal testing

To overcome that, the crucial first step, Martin adds, is to prove that the data that emerges from alternative testing methods is comparable to the correlation between current methods of animal testing and human data.

Vidmantas Šakalys, CEO of Lithuania-based startup Vital3D, which is working towards printing 3D human organs for drug testing, says this is one of the biggest challenges: "developing standardised protocols and confirming the technology's efficacy in mirroring human reactions are key for its wider application — achieving consistent and replicable results is crucial for gaining regulatory approval and widespread acceptance," he says.

“One day, I think we will see ex-vivo organs [developed outside of a body] being used for safety/toxicology studies maybe combined with technology like digital twins,” says one biotech investor at a major European firm. “But we’re far from there and we’d need a lot of data to build the latter.”

Martin is optimistic though. “We are in an era where technologies such as ImmuONE's and its applications will eventually be able to replace animal testing and refine the experiments needed to collate relevant data,” she says.

There is some movement across the Atlantic. At the end of 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) waived the requirement for all drugs to go through animal testing before clinical trials, instead accepting organoid or cell-on-a-chip data in some cases. The investor highlights that there are major caveats to this, though — the FDA is only ready to accept organoid data in specific cases where there are no existing animal models accurately reflecting the diseases that can be used for testing, rather than in the majority of cases where animal testing currently offers sufficiently comparable data to humans.

What’s next for ImmuONE?

ImmuONE used some of its recent funding to move from a 400sq ft university lab to a 1,200sq ft lab in Stevenage in the UK, in September — a move that is increasingly tricky for science-heavy startups in Europe. “Finding space is nearly impossible”, says Martin — adding that for startups targeting rapid growth, “finding enough space to grow is also difficult.”

Martin has plans to further grow ImmuONE’s headcount from its current 18, and says that she expects to grow out of the current lab when doing that. She says the company is eyeing expansion to the US during its next phase, "to better serve American clients.”

The team is also looking to expand its product roster, and would eventually consider acquiring other startups that have developed organoid animal testing alternatives, particularly from the US, Martin says.