Scottish vertical farming startup Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS) has raised one of the industry’s largest rounds in Europe, securing £42.2m in Series B investment.

IGS doesn’t sell its own crops. Rather, it sells its vertical farming systems to farmers. The company says they can help farmers actually make money from vertical farming — something the industry has struggled with.

The raise comes as the industry expands at a rapid pace. It was worth $2.2bn in 2018 but is expected to reach $12.8bn by 2026.

In Europe, an overwhelming amount of funding in the industry has gone to Infarm, a Berlin-based startup and Europe’s largest vertical farm, which has raised over $400m and is planning a public listing.

IGS secured its investment from COFRA, Cleveland Avenue and DC Thomson. It announced the funding at the Cop26 UN climate conference in Glasgow today.

Making a profit

“The system is economically viable, most other vertical farms are not,” says David Farquhar, founder of IGS. “One of our systems run by a farmer will generate cash in the first month and the payback period is between two and four years, but they can reach profitability on an operating basis very quickly — in less than six months.”

Profitability is a problem the vertical farming industry has struggled with. Infarm, which was founded in 2013, says it’s aiming to be profitable by 2023. French startup Jungle, which uses an IGS system, told Sifted that it’s aiming for profitability in 2022.

Farquhar says IGS’s system will help farmers reach profitability quicker because it uses 50-60% less energy and needs 80% less labour than other systems.

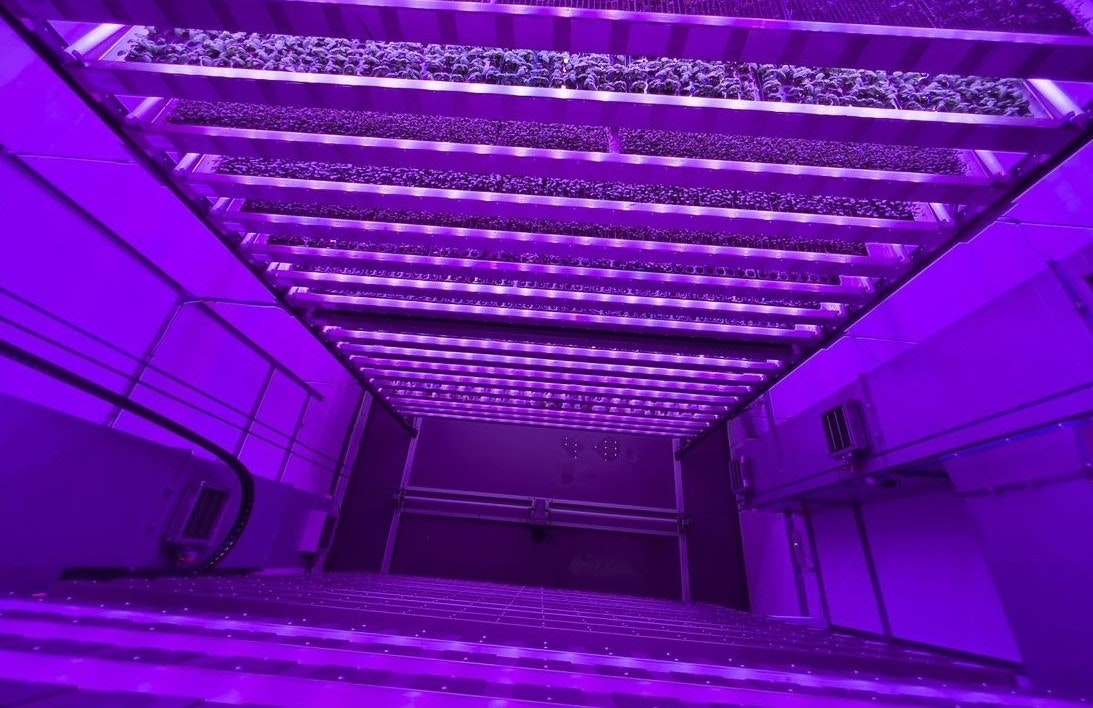

They’ve saved labour by bringing in robots. “If you see photographs of vertical farms where someone’s wearing a white lab coat, goggles, a facemask, a hairnet and carrying a clipboard, you should run a mile because they don’t know what they’re doing,” he says.

The energy saving comes from 17 patents that allow IGS to uniquely control the environment of the farm, Farquhar says.

“We're able to control the lighting. We think about the weather as a three-dimensional system, the sun, the wind, rain, and we have complete control over all three of those.”

The system is set up in towers, each with a footprint of 42 sq m. Farquhar says in that space you can grow the same amount of crops as you would in a four hectare (40,000 sq m) open field.

“Infarm decided to build their own systems,” he says. “Because of that, they've had to raise hundreds of millions of euros in order to try and get their business on the trade line. But they're not profitable.”

IGS is also working on forms of asset finance for the farms, which would mean farmers don’t pay an upfront cost. “They’ll be run sort of like farms-as-a-service,” Farquhar says.

Beyond leafy greens

Aside from profitability, the other criticism often levelled at vertical farms is that they can only grow salad leaves and herbs.

Farquhar says IGS can do more than that — it’s grown radishes, baby turnips, carrots, broccoli, tomatoes, peppers, strawberries, blueberries and potatoes, as well as “microgreens”.

It’s also being used to grow botanical flowers for the perfume industry, as well as softwood trees. It’s now working on hardwood trees. Jungle, the French vertical farm which uses IGS’s tech, is using it for botanicals and flowers, alongside edible crops.

Scaling up

“The system is highly scalable,” says Farquhar. “We can start with a footprint of about 100 m2 and we can go to 1,000 or 10,000.” It’s a modular system, so parts can be added on as and when a farm wants to expand.

IGS is now supplying its tech to farms in Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, the Netherlands, France and Germany, as well as working on deals in Oman, Saudi Arabia and the US.

He says interest is increasing as more and more countries focus on moving their supply chains closer to home, a need exacerbated by both the climate crisis and the pandemic.

“Countries like the UAE, Saudi Arabia and so on are increasingly publishing food security strategies, which have been exacerbated by the onset of coronavirus. Now people really want localised production.”