Space exploration is no longer the stuff of science fiction. As going to space becomes a feasible goal (if you have a bit of money lying around) and with the cost of building rockets falling, researchers, companies and governments are looking to space not just to explore the stars, but to solve the Earth’s climate emergency.

Overall funding for space tech dipped in 2023, with global investment being more than 40% lower in H1 than in the same six months last year, but a number of startups are building at the juncture of climate and space.

There’s also significant money pouring into the sector: the UK recently announced £65m and the European Investment Fund (EIF) announced a €60m ticket into a VC firm led by a former SpaceX exec in May.

Below are some of the areas that startups at the intersection of climate and space are exploring:

Monitoring carbon emissions

Satellite-based emissions monitoring is a growing area within space tech.

Aravind Ravichandran, founder of TerraWatch Space, an advisory and communications firm focused on Earth observation, says that the rise of ESG and emissions-related regulation has led to an increased need for satellite-based monitoring.

Kayrros, founded in 2016, uses satellite-based technology to measure the effect of human activity on the environment in real time. Based in France, the startup has raised over $44m in funding so far.

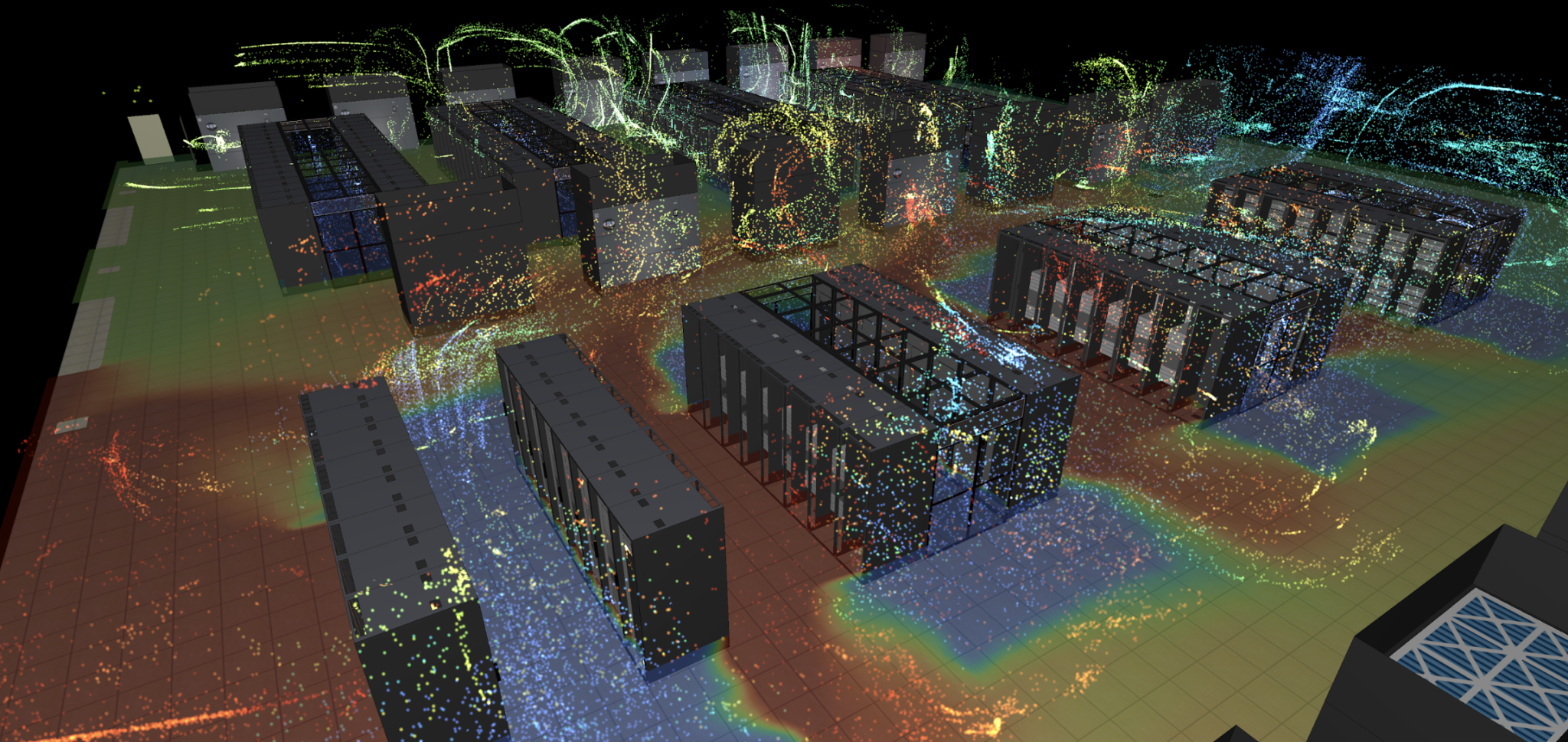

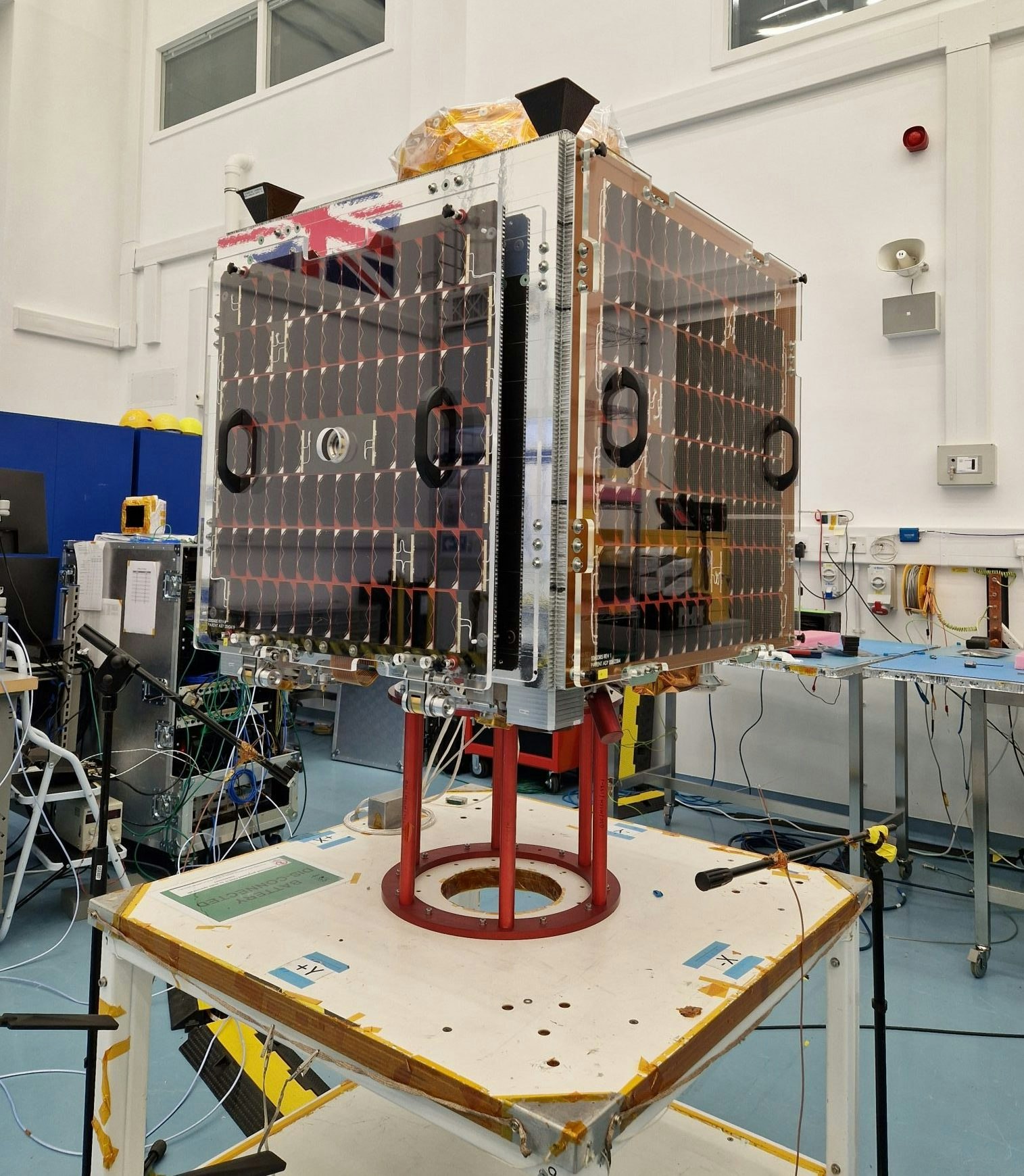

Satellite Vu, a UK-based startup, uses infrared intelligence to monitor the temperature of buildings to determine valuable insights into energy efficiency and carbon footprint. Anthony Baker, cofounder of Satellite Vu, says that while satellite-powered software like Google Maps helps you monitor only what happens during the day, thermal imaging offers real-time monitoring both during the day and night.

“You can look at a warehouse or a battery and see whether it's on or off, and you can count how many shifts they’re working,” Baker says. The startup launched commercial operations earlier this month.

Other startups working on satellite-based emissions monitoring include UK-based Carbon Diem, which provides users with estimates on their carbon footprint based on their travel plans.

Monitoring rain or shine

Satellite technology has been used to predict the weather for a long time, but as extreme weather becomes more prevalent, the demand for weather monitoring tech — particularly from the insurance sector — is on the rise.

Weather and climate intelligence startups are expanding into a number of areas, from helping improve the output of clean energy to predicting and reducing the impact of climate disasters using weather monitoring.

Despite a tough fundraising environment, weather intelligence startups saw their second-best funding year in a decade in 2022, with $266.4m raised in venture capital. Radar imaging startup ICEYE, which offers near real-time natural disaster monitoring solutions, raised $136m in a Series D funding round in 2022.

Italian company Flyby uses satellites to accurately predict the power output of solar power plants and helps identify faults, which could otherwise reduce energy production by more than 10% a year.

Weather-monitoring tech is also being used to make clean energy more efficient. To maximise the amount of electricity from new wind turbines, French startup Leosphere developed a small instrument to measure wind speed and direction. In 2018, it was acquired by Finnish weather and industrial measurement company Vaisala.

Up close to the sun

Space-based solar energy uses solar panels attached to satellites to capture energy and send it to ground stations as microwaves.

Sam Adlen, co-CEO at Space Solar, a startup that aims to develop and commercialise space-based solar power, says that the key benefits of using space-based solar power instead of terrestrial solar energy are that it can run round the clock, be scaled massively and has high “dispatch ability” to be transported across vast distances.

While the technology has long been criticised as too expensive and technologically challenging, as the climate crisis worsens, governments and research institutions around the world are reconsidering its potential.

The European Space Agency (ESA)’s Solaris is a three-year R&D programme that aims to advance space-based solar power. Sanjay Vijendran, the programme’s lead says that the goal is to get all the data needed “to make an informed decision by 2025 or so on going ahead with full development, with the aim of having commercial power plants in orbit in mid to late 2030s."

Not everyone shares the optimism about harvesting solar power in space. “For me, it is far-fetched because of the costs and risk involved,” TerraWatch Space’s Ravichandran says.

Researchers and scientists are also exploring other possibilities such as planetary sunshades that can be created in space by cannons shooting dust from the Moon to help partially shield sunlight to Earth.

While the ESA has an ongoing study on planetary sunshades, Vijendran says that it is a last-resort that could be used if the situation on the planet gets worse. It would also require heavy infrastructure to be built on the Moon to launch dust into space.

Infrared-powered agriculture

Real-time thermal imaging is also being used for agriculture and irrigation management, as agribusinesses are increasingly having to monitor water stress and climate impact, with extreme weather events brought on by climate change and global food insecurity on the rise.

Luxembourg-based Hydrosat, which uses thermal data and analytics to accurately forecast crop yield, raised a $20m Series A round earlier this year, enabling it to put its first two thermal infrared satellites into orbit.

German startup Constellr also uses imaging technology to assess vegetation, soil health, and industrial monitoring for the agriculture sector, and raised a seed round of €17m in July.

Growing the sector

Despite significant fundraising and a large potential market, there is still scepticism around feasibility and cost.

Ravichandran cautions that there remains very little commercial interest. “One of the big factors for [low commercial interest] is that there is free data available in the public sphere,” he explains.

The US, European Commission and European Space Agency satellites all produce data that is freely available and, as such, it is hard sell to persuade private companies to pay for it.

But tailwinds could come as incoming regulation requires companies to provide more granular reporting on their emissions, a move that could increase demand for more detailed satellite data and analytics.

Climate-focused space tech startups face the same hurdles as the wider space tech industry: insufficient regulation, military and national security concerns and the risk of satellite debris polluting space.

But a challenge particular to climate tech solutions is data inequality, says Ravinchandran, in that there is a lack of weather data for the Global South, the area most affected by climate change.

“Just because the satellite is collecting data from around the world does not mean that data from every part of the world is going to be equal or accurate — we still need to go on the ground and measure it,” he says.

Adlen, Vijendran and Ravichandran all agree that international collaboration is key to overcoming the challenges faced by space-based climate tech.

“Space has always been a great area for international collaboration, and we can retain that,” Adlen says.

Ravinchandran says that energy independence and climate change are deeply political topics that can make collaboration tricky — but there are already governments collaborating in climate science data.

“While people talk about the International Space Station a lot, the partnerships that happen for weather and climate science are often underrated, where we have data being shared and discussed between different countries even in between all the conflicts happening in the world,” he adds.

“So it's important to remember that there are some cases where collaboration can supersede in a way.”