Tom Peeters, cofounder of the online supermarket startup Crisp, has been on a hiring spree. He has employed 30 people in Amsterdam since the company started a year ago, and he is keeping his eyes peeled for more.

Finding people is easy, he says, as locals increasingly prefer to work for startups than the big companies. “More and more people don’t want to work for the big brands; they want to work and contribute to something that matters,” he says.

Employment in the city’s tech sector is up 12% in the past two years to 69,000.

Companies such as Crisp are responsible for a huge jump in the number of tech workers in Amsterdam, with employment in the city’s tech sector up 12% in the past two years to 69,000, according to new data from Dealroom released on Wednesday in conjunction with StartupAmsterdam.

Of those roles, 37,000 workers are employed at startups and scaleups; that’s 7% of the total jobs in the city. Amsterdam now has 1,213 home-grown startups with under 50 employees, which between them employ over 14,500 people.

On top of that, 128 local tech companies have over 50 members of staff — and between them employ over 15,700 people.

All this means that, according to Dealroom, young tech companies are adding more jobs to Amsterdam’s economy than any other sector.

Homerun

One of the companies on the coal face of this Amsterdam hiring spree is Homerun.

The four-year-old software startup helps other companies with their hiring process, and so has benefited from the hiring boom.

“We’re in this to bring out the unique side of smaller companies, to enable them to attract talent that connects with their values, so they can compete with the Airbnbs and Googles,” says Willem van Roosmalen, cofounder of Homerun and a designer by training.

Homerun helps companies of 5-500 people, hiring for between one and 30 roles, design a company hiring page, craft and promote job ads, and manage the hiring process.

In a little example of what can make smaller companies “unique”, this month Homerun celebrated its fourth birthday, and invited friends and family — including its 18-person team’s parents — round for a party.

View this post on Instagram A little throwback to last week, when we invited our families to celebrate our 4th anniversary ?? A post shared by Homerun (@homerun.co) on Apr 5, 2019 at 4:38am PDT

“Work has become such a vital part of life, but lots of employees have never brought their parents to work before,” says van Roosmalen. “Often [parents] don’t understand the choices our generation make — around finding purpose in work, surrounding yourself with people you like. It’s not just a paycheque anymore.”

Talent in Amsterdam tends to be looking for three main things, says van Roosmalen: finding purpose in their work, company culture, job security, and a decent paycheque.

“In tech, there are some very well-known companies people want to work for, like Booking.com. More interestingly, there’s an entire range of [Homerun] customers, like payments software startup Mollie, that really value work-life balance.”

He adds: “Then there are a lot of companies which aren’t in tech but are ‘tech minded’ which are very popular places to work, like [ethical chocolate maker] Tony’s Chocolonely, [eyewear company] Ace & Tate, [file transfer business] WeTransfer and sustainable bottle company Dopper.”

That said, van Roosmalen says there are still plenty of people in Amsterdam working for larger corporates who are “afraid to make the switch to startups — they think their skill sets don’t fit the smaller, faster, lean environment — which I think is a shame.”

Attracting international talent is no problem though, he thinks; the city’s character sells itself.

There’s a sense of laidbackness when you compare Amsterdam to London or San Francisco or Paris or Berlin.

Over half the city’s developers (who remain the hardest to hire) are from outside the Netherlands. “There’s a sense of laidbackness when you compare Amsterdam to London or San Francisco or Paris or Berlin for that matter. It’s really in line with the cultural heritage of Amsterdam; it’s a very liberal city.”

Crisp

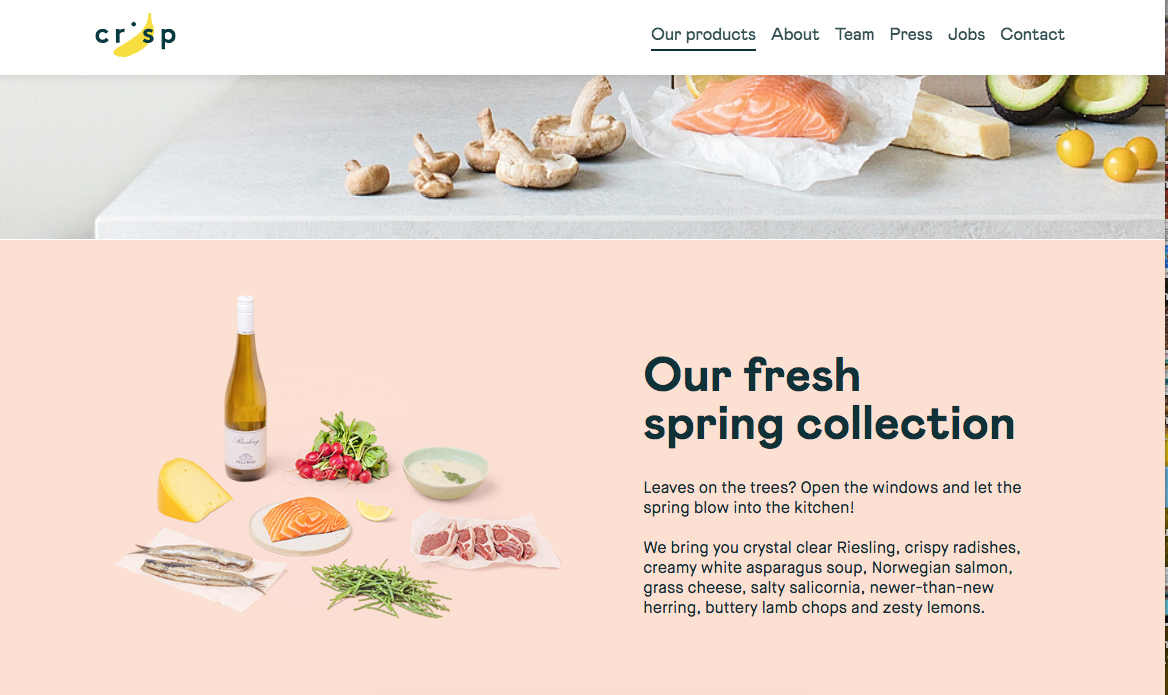

“Grass cheese, salty salicornia, newer-than-new herring”: the advertising for Crisp is a sure sign that the online supermarket is a) Dutch b) seasonal and c) fresh (both the produce on offer, and the design).

Launched in November 2018, Crisp connects local farmers directly to customers via its app (much like the UK’s Farmdrop), and offers home delivery six days per week. It offers 1,400 different products, from fruit and veg to prepared meals, and is proving popular with young families.

If you look at it like a football team, if your first hire is Lionel Messi, it’s always easy after that.

Crisp has (with one exception) done all hiring in-house, mostly relying on its four founders’ networks. “If you look at it like a football team, if your first hire is Lionel Messi, it’s always easy after that,” says Peeters, who claims it hasn’t even been a struggle to hire good developers at Crisp — although the team did interview over 70 candidates for the last engineering role.

“Start with that in your mind, then take careful steps adding talent to talent. Then people will start reaching out to you.”

Crisp's 30 employees have a range of employment experience: some have come from grocery giants like Albert Heijn; others from fellow consumer startups with a core logistics component like Hello Fresh and Bloomon; while Crisp’s warehouse manager is ex-Royal Dutch Marine Corps. But they all want to make an impact on the world, says Peeters. “It also why I’m doing this: I want to build something I can be proud of, because of what the business is and does.”

I want to build something I can be proud of, because of what the business is and does.

The Dutch are latecomers to the online grocery game; while in the UK 6% of grocery is bought online, in the Netherlands it was just 2.5% in 2017. (Online supermarket Picnic — the startup which has been on the biggest hiring spree in Amsterdam over the past two years — is helping to swiftly change this.)

Yet, like many of their European neighbours, the Dutch are also becoming increasingly interested in knowing where what they buy comes from, who makes it and who makes money from it.

“People are changing how they shop — moving from offline to online,” says Peeters. “But they’re also changing what they shop. We’re seeing a significant push away from the big brands — which publish their ingredients label in the smallest legal font size — towards more transparent, healthier, fresher food. We’re building a business in the intersection of those two trends.”