When Amanda Feilding was 10 years old, she remembers witnessing liquid tears fall down the painted face of Jesus Christ, on a picture hanging in her local church.

She thinks of it as a mystical experience, and one that informed a life that’s taken her from living with Bedouins in the Syrian desert to campaigning with Andy Warhol to becoming director of a multimillion-dollar startup.

She tells me this from the dining room of Beckley Park, a 16th-century hunting lodge surrounded by three moats and a topiary garden of ornately sculpted hedges in rural England. Her childhood home is now the headquarters of one of the world’s leading experimental psychedelic medicine startups: Beckley Psytech.

The company is more than a business to Feilding, who has spent more than 50 years trying to change society’s perception of psychedelic compounds and the altered, and sometimes mystical, states they induce.

Now, with more than $80m of investment behind her, she believes the world is starting to listen, as psychedelic-assisted therapy becomes one of the most interesting sectors hoping to tackle the mental health crisis.

A delayed brunch

Trying to conduct a choreographed interview over brunch with Feilding is a bit like trying to catch a hurricane in a fishing net. Once she gets going on a subject it’s easy to forget that there’s coffee to be drunk and food to be eaten.

When I enter Beckley Park’s dining room I notice a photo book of the Chauvet Cave paintings, prehistoric artwork thought to have been drawn on the walls of French caves some 30,000 years ago. I ask Feilden about the book, and she is immediately animated.

“I am utterly convinced they were painted under altered states of consciousness,” she says.

What follows is a lively discussion about the nature of abstract thought, and the role that altered states have played in the history of human culture. The conversation is halted by the arrival of Cosmo Feilding-Mellen, Feilding’s son and the CEO of Beckley Psytech, who has a lunchtime appointment to get to.

We take our seats in front of a stone fireplace that covers a whole wall. It’s decorated with frayed silk hangings that look as though they’ve been part of the house longer than Feilding, who turned 78 this year.

Mystic healing

So, how are the mystical experiences that Feilding is telling me about relevant to Beckley Psytech’s business model?

She points me to the results of a 2018 study conducted by Imperial College London in partnership with The Beckley Foundation, a non-profit psychedelic research organisation founded by Feilding in 1998.

The study saw 20 patients with severe depression undergo treatment with psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in “magic mushrooms”. The results showed that those who reported a stronger mystical experience were more likely to show positive outcomes in terms of a reduction in symptoms of depression.

As Feilding sees it, this is evidence that mystical experiences are real, valuable and central to our human condition.

“What has basically been at the centre of religions — which is the mystical experience — is also at the core of the healing process of psychological illnesses like depression, addiction, post traumatic stress disorder,” she says. “I think it's rather a beautiful revenge of science, coming back to reintegrate mystical experience, because I think our culture does lack spirituality as a kind of scaffold.”

As Feilding ponders the nature of the mystical experience, her son interjects to remind us that there’s a fully prepared brunch waiting on the counter behind us — a colourful spread of toast, eggs, avocado, smoked salmon and tomatoes.

Like mother, like son

Dressed in a green velvet blazer and bejewelled belt, speaking in the clipped and articulate English of the British upper classes, Feilding lives up to her reputation of the “eccentric aristocrat”.

Feilding-Mellen, meanwhile, is the more modern face of Beckley Psytech and affably plays the role of reining in his mother’s obvious personal passion for psychedelics.

“LSD is a very incredible compound for its purity… I think it's particularly good because it's completely non-toxic. You can't kill with an overdose, which is amazing,” Feilding tells me, eliciting a playful, under-the-table kick from her son, trying to keep her on message.

And while Feilding’s work with The Beckley Foundation has made her one of the world’s leading authorities on psychedelic science, her son is aware that a whole new set of challenges lie ahead in turning Beckley Psytech into a profitable pharmaceutical company.

“The logic behind setting up Beckley Psytech was that there’s this body of evidence that’s been generated in an academic setting, in early stage, proof of concept settings. Now the next step is to actually take these drugs through the drug development process,” he explains. “That requires a lot more funding and a lot more expertise that goes beyond academic research to actual drug development. Thinking about pharmaceutical development, regulatory pathways and market access. All of those types of things.”

Aside from mental health conditions like treatment resistant depression and addiction, Feilding-Mellen is hopeful that psychedelics could be used in the future to treat a broad spectrum of neurological conditions.

One that he points out is the chronic condition SUNHA (short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks), which can give patients as many as 100 severe headaches a day and currently isn’t treatable with medication. In January this year, Beckley Psytech secured regulatory approval to begin a clinical trial investigating the effects of psilocybin in the treatment of SUNHA.

This possible clinical application for psychedelics would likely take the form of microdosing psilocybin (a technique which involves taking the substance at a low dose), Feilding-Mellen explains.

This prompts an enthusiastic interjection from Feilding, on how microdosing can “oil the doors” to prepare people for more “challenging” psychedelic experiences at higher doses. The comment earns her another kick under the table from her son, who prefers to focus on Beckley Psytech’s impressive roster of hires from the world of big pharma.

Both Dr Steve Wooding, the former head of global commercial strategy and market access at Janssen, and Dr Fiona Dunbar, former vice president of global medical affairs at Janssen, have been with Beckley Psytech since it launched in 2019. The team now totals more than 40 people all working to bring the company’s treatments to market.

The religion of science

These aren’t the only big names from institutional science that have thrown their weight behind the promise of psychedelic therapy.

Feilding has previously collaborated with researchers like David Nutt of Imperial College London (and formerly the UK government’s chief adviser on drug misuse) and Colin Blakemore of Oxford University on a number of studies.

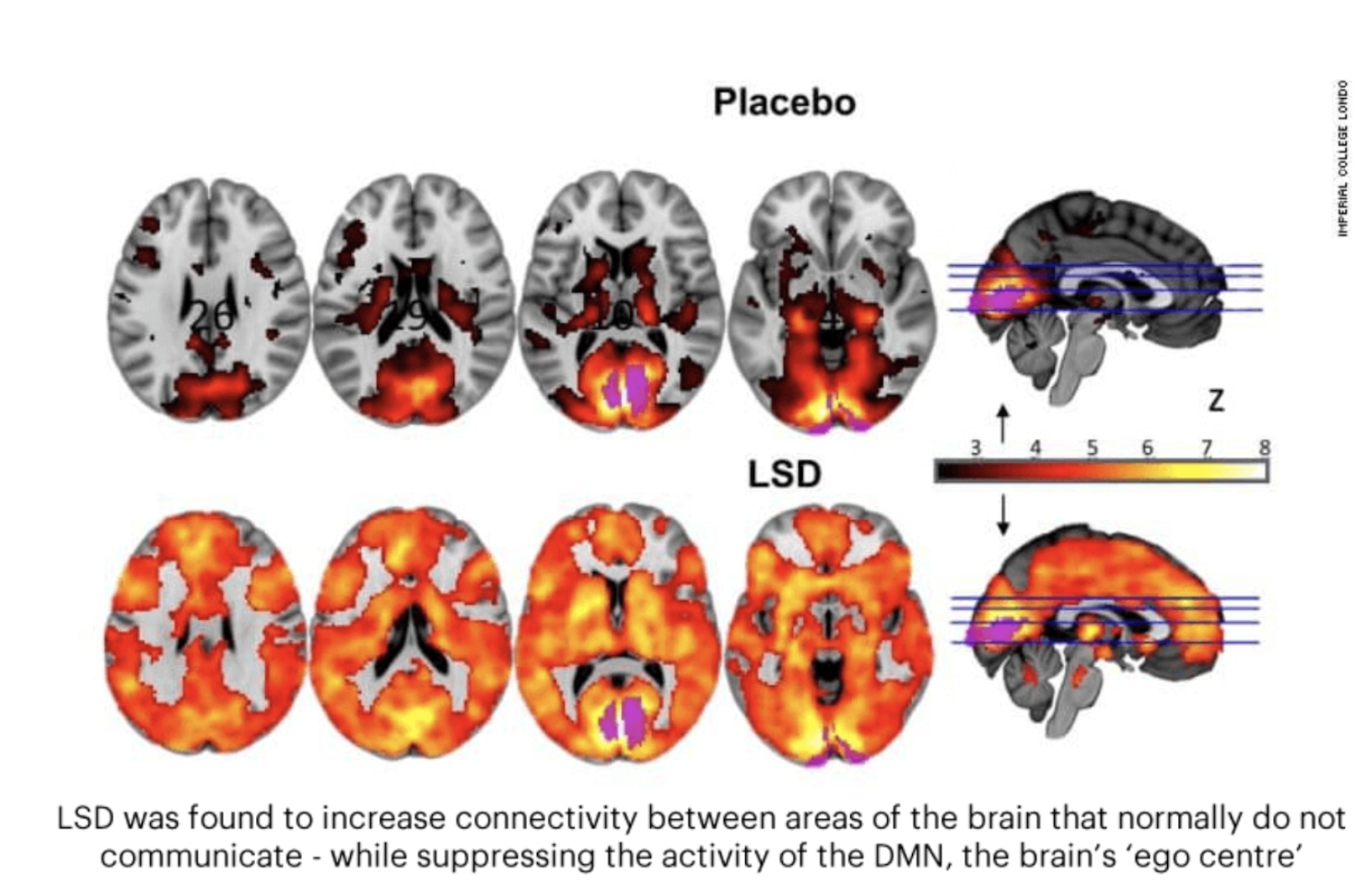

In 2016 the Beckley Foundation and Imperial College London completed the first-ever piece of research using neuroimaging to show the effects of LSD on the brain.

The results are visually compelling, showing a far greater level of electrical activity in the brain while under the influence of the psychedelic, and were the realisation of a long-held goal in Feilding’s quest to destigmatise these substances.

“I realised in the late 60s that the only way through the ever increasing taboo was with the very best science. That was the new religion, so one had to prove through the new religion that these compounds were factually advantageous,” she says. “That's why when brain imaging evolved, I suddenly realised, well, I have to become a foundation and use brain imaging because it can give you a visual perspective that you can’t deny.”

Feilding and the Beckley Foundation went on to become trailblazers in the newly re-adopted psychedelic research community, a field that had lain dormant since Richard Nixon cracked down on psychoactive drugs.

Studies carried out with support from the Beckley Foundation have separately demonstrated the potential of psychedelics to treat nicotine addiction, depression and end-of-life anxiety in terminal patients.

A hell of a life

The fact that Beckley Psytech is now attracting investment to try and bring psychedelics into mainstream medicine is evidently a source of great satisfaction for Feilding.

“It feels very good,” she says with a smile. “We’ve reached the foothills, but it’s taken 50 years to get there.”

That 50-year journey is one that’s taken her from a family life steeped in the traditions of the British aristocracy — her formal title is the Countess of Wemyss and March — to one that’s earnt her nicknames like “the crackpot countess” and “Lady Mindbender”.

Her first act of rebellion against the mainstream came when she was 16 and a student at a Catholic school. After winning a poetry prize, she requested a book on mysticism as her reward.

When the nuns declined her request, she decided to leave school and hitchhike to Sri Lanka in search of her godfather Bertie Moore, who had converted to Buddhism.

Feilding only made it as far as the Syria, where she encountered a tribe of Bedouins who she lived with for some months before returning to England.

She’s hung out with Mick Jagger, had Allen Ginsberg crash on her sofa in her London flat and received the support of Andy Warhol for her installation art.

Feilding is perhaps most notorious for a surgical procedure that she performed on herself called trepanation. In 1970, she drilled a hole in her own skull in the belief that the ancient practice could increase blood flow to the brain.

Feilding still believes that the procedure comes with “subtle” benefits, but now strongly advises against people following her example and trying to trepan themselves.

Today she is more focused on the cutting edge psychedelic medicines that Beckley Psytech is hoping to validate in clinical trials, and believes that society has a lot to gain from their reintegration into society.

“I think altering the state of consciousness widens the viewpoint and, from our research, we've shown that it increases all sorts of beneficial qualities like resilience, mindfulness, compassion, a love of nature,” she says.

And with a global pandemic, climate crisis and mental health crisis in full swing, those all feel like useful qualities to foster.