With a projected market size of $290bn by 2035 and an ever increasing awareness surrounding animal welfare and the environment, the alternative protein market is set to beef up substantially.

Consumer demand for burgers that look like burgers — but aren’t made from cows — has hit an all time high, and investors are also keen to take a bite. In 2020, funding for European alt protein startups increased by 178% — from €203m in 2019 to €566m. The sector recorded the most significant growth in European foodtech.

The stakes are high. Raising livestock generates 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions — and those in the alt protein space claim that switching to plant-based alternatives is not only more sustainable, but more nutritious too.

But can Europe’s batch of alt meat startups make tasty, scalable and affordable enough products to capture the market?

We’ve spoken to the European alt meat players — and foodtech investors — to find out what opportunities and challenges await the sector.

Who’s in the running?

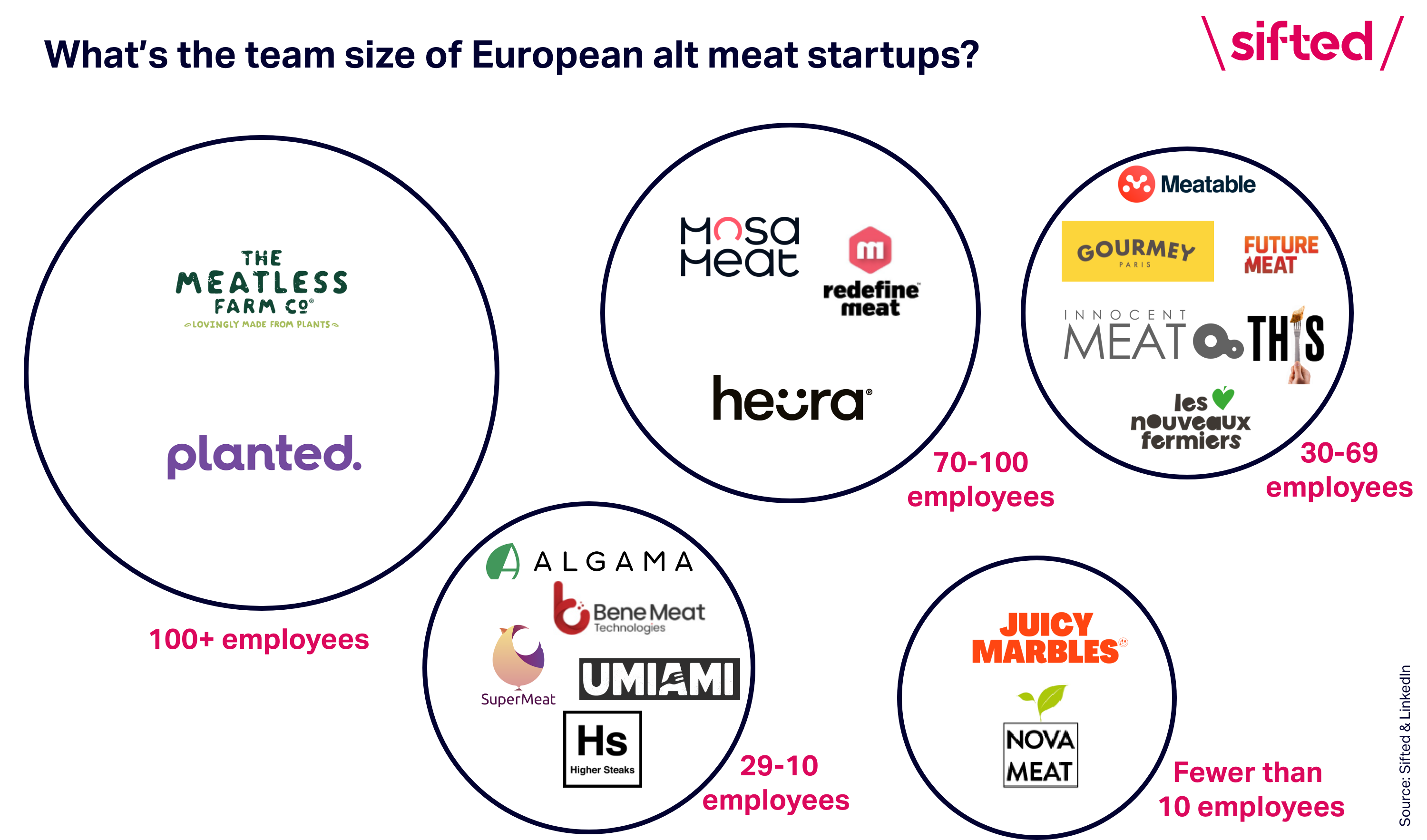

More than half of the European players were founded in the past three years — and they’re growing quickly. Swiss startup Planted, which makes plant-based meat products for supermarkets and restaurants launched operations in summer 2019, already has a team of 100 and has expanded to Germany, France and Austria. UK startup This, which makes plant-based chicken and bacon also launched in 2019 and has landed deals with big retailers and restaurants like Tesco and Waitrose.

Most of the companies produce alternative meats in one of two ways. They’re either plant-based — ‘meat’ made from plant proteins like soy or pea, or cell-based — grown from real animal cells. A lot of the products are chicken, beef and pork-based but there are some more unique products too. London-based Moving Mountains offers plant-based fish fingers, Paris-based Gourmey has developed a cultivated version of the French specialty foie gras and Spain’s Heüra Foods produces plant-based veal. Spain’s Novameat 3D prints plant-based meat, and says it’s developed 3D-printed hybrid meats which mix plant-based and cultivated meat together.

Who are they selling to?

Many commercially active alt meat startups have formed partnerships with supermarkets and restaurants — the former taking priority in the past year due to restaurant closures.

UK-based startups This and Meatless Farm sell their products in big supermarkets like Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons, while France’s Les Nouveaux Fermieres has wooed big French retailers like Carrefour and Monoprix. Other startups, like Moving Mountains, shifted focus from restaurants to supermarkets as a result of the pandemic — and rising demand.

“The fact supermarkets are allocating more space to these products means they can see there is growth in this category,” says Moving Mountains’ founder Simeon Van der Molen.

That’s not to say that restaurant partnerships have been completely written off. This sells its products at Italian restaurant chain Prezzo and burger restaurant Honest Burger, while Spain’s Heüra Foods has partnered with Asian food chain Udon and fast food sandwich chain Pans.

Some startups are even launching their own restaurants. SuperMeat, a cell-based meat startup, opened a restaurant in Tel Aviv called The Chicken where customers can try its cultivated chicken. Planted is opening a fully plant-based restaurant later this month in Zurich.

But startups aren’t the only ones tapping into the alt meat market; corporates have eyed it up too. Nestlé dipped its toes into the market with its Garden Gourmet brand in 2018, and big supermarket chains have also launched their own plant-based meat brands, like German supermarket Kaufland’s K-Take it Veggie and Lidl’s Vemondo.

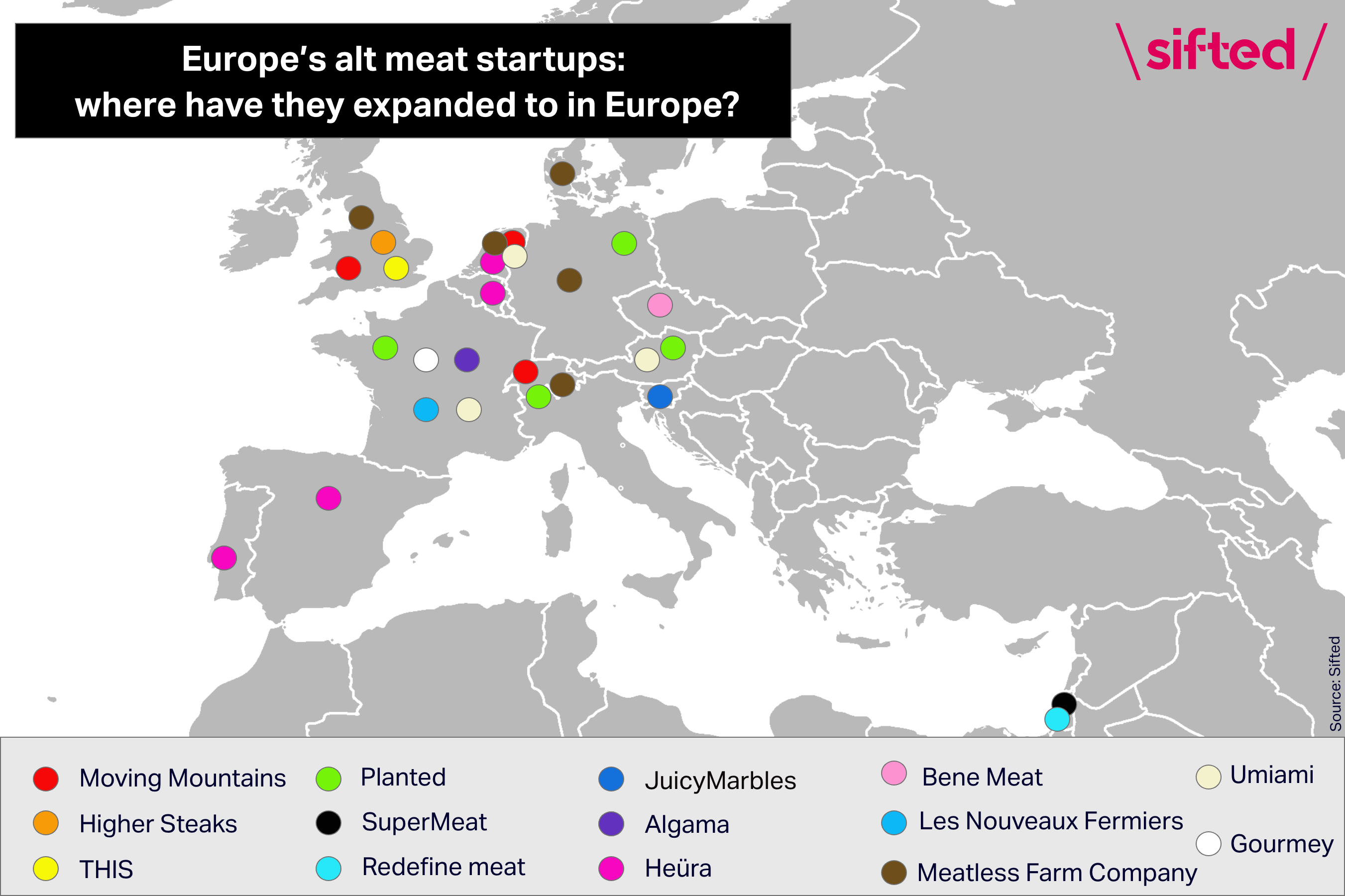

Which markets are they trying to win?

“Big markets everybody's looking at [in alt protein] are Germany, the UK, the US and Asia — China has quite some movement,” says Christoph Jenny, cofounder of Planted.

The Netherlands is also an attractive market for many startups — Moving Mountains, Meatless Farm, Heüra Foods and Umiami have all launched their products there, despite not being based in the country.

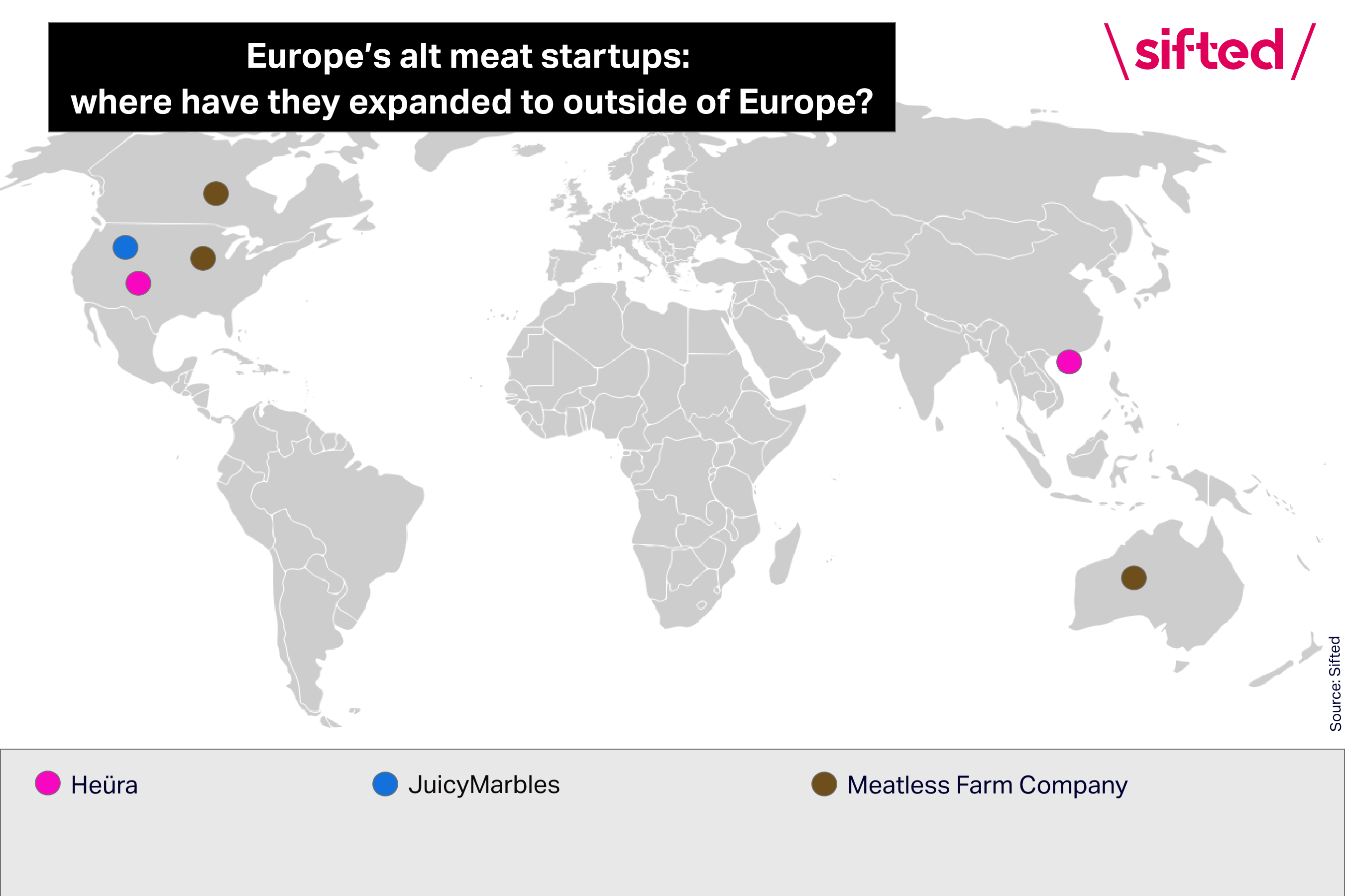

For the cell-based players like Mosa Meat, regulatory barriers differ from market to market, meaning that market entry can take a lot longer. This is mainly because regulators identify cell-based foods as ‘novel’, or not having a significant history of consumption to date.

Last year, Mosa Meat’s head of strategy Sarah Lucas gave Sifted details on the roadmap to bringing its cell-based beef burger to the European market: “In the next three years, we aim to scale up to one industrial-sized production line, work with regulators to demonstrate the safety of cultivated meat, and introduce the first cultivated beef to consumers.”

Maarten Bosch, chief executive at Mosa Meat says that it's also looking to get regulatory approval in Singapore and sees “a regulatory path to market in the US and the UK.”

Other alternative meat startups have expressed interest in expanding into the US and Asian markets in the near future, including plant-based meat startups like Israel-based Redefine Meat and Barcelona-based Novameat. British cell-based meat startup Higher Steaks also wants in on the US and Asia as well as Prague-based startup Bene Meat, which aims to sell protein technology to meat processing companies.

According to Benjamina Bollag, the founder of Higher Steaks, British startups have a cultural and financial advantage over those based in the US. “People here care a lot more about where their food comes from,” Bollag says. She points out that British supermarket Waitrose sells its organic meatballs for £12 per kilo (Higher Steaks plans to sell its cultivated pork for £10-20 per kilo).

“While that can be a bad thing in some ways — people have a lot more disregard for genetically modified organisms (GMOs), for example — the good thing is customers are happy to pay a premium, and prices are much higher than the US, which means the barrier for us is a lot lower.”

Consumers across the European market are also becoming more curious to try these products. Louis Magaldi-Charles, investor at French foodtech-focused VC Five Seasons Ventures says that there’s a rise of ‘flexitarians’ — people who consciously cut out some (but not all) meat — in the market. A recent report by Berlin-based plant-based supermarket chain Veganz found that 22.9% of Europeans fit the flexitarian demographic.

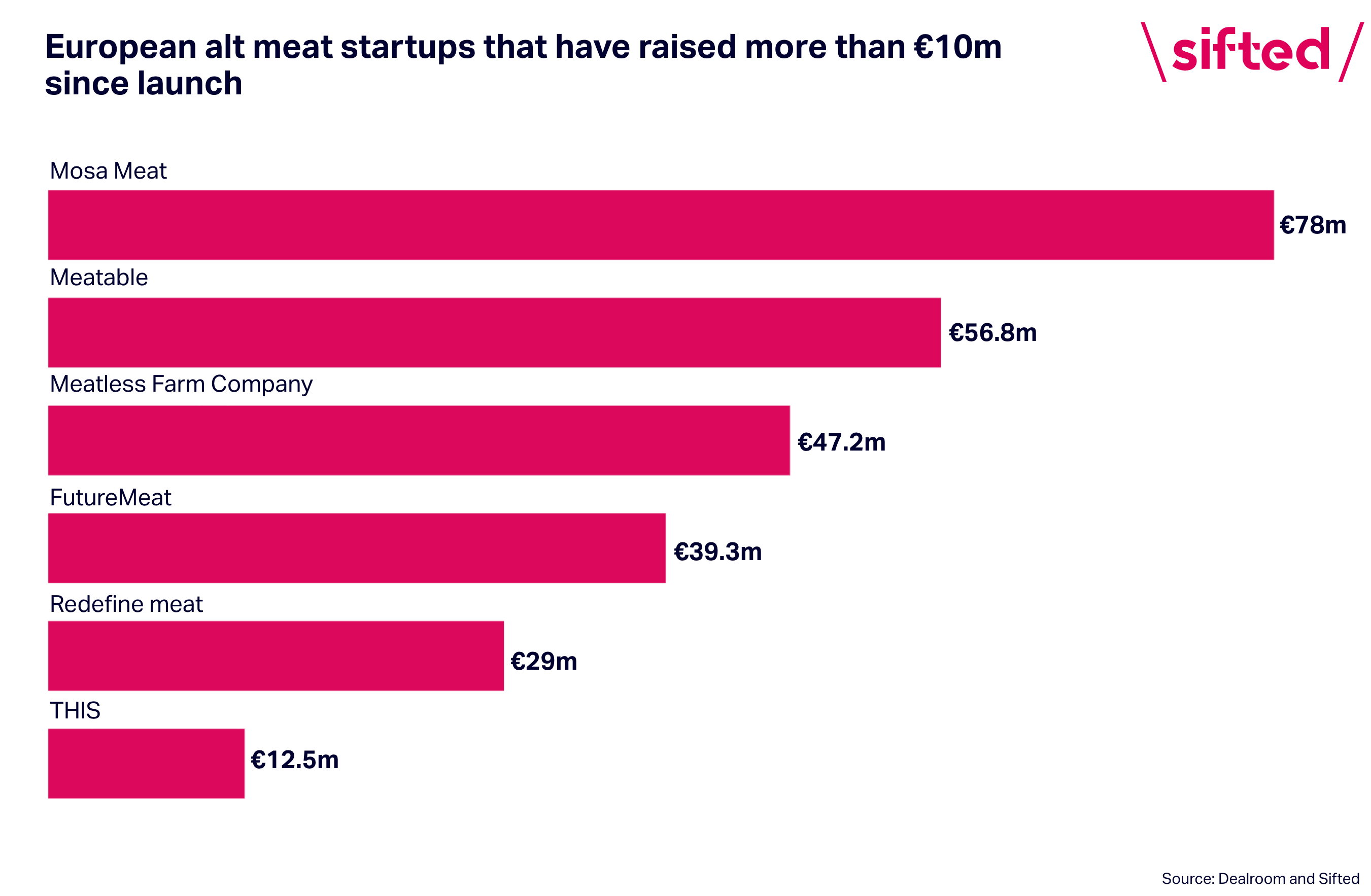

Who’s got the most cash?

Cell-based startups have taken the most dosh home so far, despite them not bringing their products to market yet.

Mosa Meat, which made the world’s first cell-based beef burger in 2013, has raised €78m. Meatable, which is backed by mega angel investor Taavet Hinrikus follows slightly behind with €56.8m and FutureMeat, which manufactures technology for the production of fat and muscle-cells for alt meat, has raised €39.3m. Over in the plant-based clan, Redefine Meat has raised the most at €35m, followed by This with €12.5m and Heüra says it’s raised over €4m.

European investors which have backed at least one of the startups include nutrition-focused VC Blue Horizon Ventures, foodtech investor Five Seasons Ventures and seed investor Seedcamp. Corporates have also dabbled in alt protein investments, including British broadcaster Channel 4, animal nutrition firm Nutreco and dairy company Muller. US investors include Y Combinator, agriculture-focused VC New Crop Capital and climate tech VC Lowercarbon Capital.

M&A activity has been pretty steady. Dutch alt meat manufacturer Vivera was acquired by Brazilian food production giant JBS in April, while Swedish plant-based meat startup Oumph! got snapped up by US-based plant meat maker Live Kindly last year (it also acquired Germany’s Like Meat last year).

“We expect a new wave of acquisition — large food corporates need to innovate and need to expand their product offering — and the market is asking for it,” says Five Seasons’s Magaldi-Charles.

He adds that corporates may buy up cell-based alt meat startups too, primarily for the technology.

Challenges ahead

Cell-based meat startups have some catching up to do when it comes to bringing their products to market, says Bosch. “It’s one thing to make one product but it’s another thing to make a billion of the same product. Scaling up is really one of the big challenges that the entire industry faces.”

Magaldi-Charles says cell-based startups might be behind their plant-based competitors when it comes to scaling, but ahead when it comes to taste. “The first versions [of the food] were a bit dry, but now we’re getting better versions of prototypes,” he says. Mosa Meat and Meatable claim (as you might expect) that their cultivated meat has the same taste and texture as traditional meat.

Plant-based products are going down well with gourmands too, though. Moving Mountains’ plant-based sausage burger received a three-star Great Taste award in 2020, and earlier this year Redefine Meat tested meat eaters with its 3D printed alt meat blind taste test to which 90% of them cited enjoying the food.

And like most other sectors that haven’t reached full scalability, price is the other elephant in the room.: “For cell-based startups, the challenge is getting down to a price that can compete with premium meat,” says Magaldi-Charles.

Some are slowly getting there, however. Israel’s Future Meat announced last month that it can create 110g of cell-based chicken breast (around two breasts) for under $4, with the price expected to drop below $2 in 12-18 months. The average cost for one regular chicken breast sits at $3.30.

Regulatory barriers for alternative meat remain a headache for alt meat startups hungry to innovate, slowing the road to commercialisation. Mosa Meat’s Bosch says that Europe is still figuring out its regulatory path but some markets, like Singapore, are looking more promising. In December 2020, Singapore became the first country in the world to issue regulatory approval for lab-grown meat.

It’s not just regulators who might slow down the alt meat startups. The meat industry is also doing what it can to halt their progress. Recently, Heüra Foods was sued by Spanish meat companies for its billboard campaign highlighting the harm the livestock industry is doing to the environment. The court dropped the case, however, saying Heüra's advertisement was scientifically factual.

“The meat industry is hitting back in certain countries on what you can and can’t call [alternative meat] products,” says Planted’s Jenny. “[But] we do have to work together and make sure legislation is drawn up fairly.”

Magaldi-Charles agrees that despite the rift between alt meat and big meat companies, they’d do better off to build relationships with one another: “In the US, the joint venture of Beyond Meat and PepsiCo announced earlier this year to sell plant-based snacks and drinks has been well received by the market and has made Beyond Meat shares rise about 26%.”

“My conclusion would be that there are some opportunities to grasp for startups rather than pure challenges.”