This is the first of a four-part series on how the western military is embracing startups to give them a technological edge. The next three dive into specific issues of augmented humans, drones and AI/data.

When Azerbaijan emerged victorious late last year, in the 44-day war against Armenia for control of the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave, it was widely believed that it was Turkish TB2 drones that had helped them win.

The drones weren’t made by a big defence conglomerate though, but by a relatively small Turkish car parts manufacturer-turned-drone company Baykar Makina.

They cost as little as $1m to $2m each according to analyst estimates — far less than the near $20m per drone price of the high-end Protector drones used by, for example, the British military. Though they had a smaller range than the more expensive drones, they could loiter in the air longer and were more expendable, bringing a new type of tactic into aerial warfare.

The tactical edge provided by such a new piece of kit from a small company was yet another wake-up call for western defence departments that they were falling behind by not tapping into new technologies fast enough, and has added fuel to the mounting calls from within the military establishment to further tap into the power of private sector innovation.

In spy movies it looks like they are on top of all this technology, but the reality is very different.

“Our Department of Defence over the last two decades has struggled connecting with innovative technologies,” says Tom Nelson, director at BMNT, the US-based defence innovation consultancy.

“To remain competitive in the 21st century, we need to figure out how to make use of the technology that is coming out from the US and Europe. Commercial companies are far ahead of the Department for Defence and that technology is available for everyone — how does our military establishment stay ahead? They have to do it by cracking the code on how to work with startups.”

Startups that work with the military are often slightly shocked at how outdated military equipment is.

“In spy movies it looks like they are on top of all this technology, but the reality is very different,” says Arnaud Guerin, cofounder and CEO at Preligens, the French startup that develops AI-aided surveillance systems for military use.

Elite forces like the SAS will all buy their own kit off the market. But do you want your military to buy their kit off the shelf, usually made in China?

Military systems aren’t connected to the internet, for a start, so there’s no opportunity to connect to the kinds of whizzy SaaS services that have become the norm for most of us — it's a case of decades-old on-premise mainframes and sometimes sneakily connecting to things via a personal mobile phone.

“If you move away from the big bits of equipment like tanks and planes, everything the military uses is behind what is commercially available in the market,” says Charlie Curtis, associate partner at Sia, the innovation consultancy which does a lot of work with defence customers.

“Elite forces like the SAS will all buy their own kit off the market, because they can get better rifles, scopes and drones. But do you want your military to buy their kit off the shelf, usually made in China?”

So how are militaries around the world responding to this challenge? How are they engaging with new tech and startups?

A rush to build accelerators

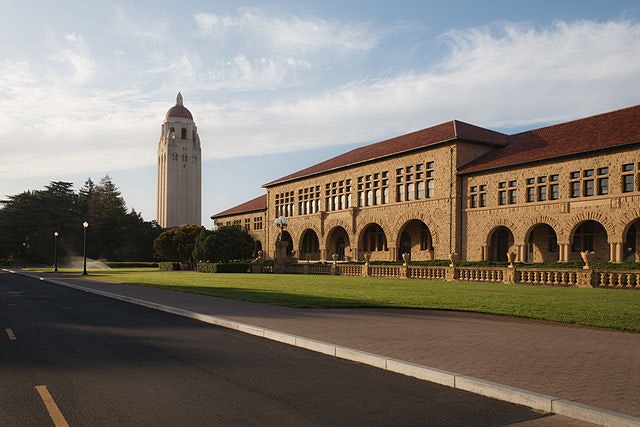

This fear of being outpaced by technological change is part of the reason why BMNT and Stanford University started the Hacking for Defence programme in the US in 2016, getting university students to work on solving challenges set by the Department of Defence.

The UK’s Ministry of Defence started operating a similar programme two years ago, and it is now being extended to a Hacking 4 Allies programme which will work with startups.

Innovation doesn’t come from within the defence sector the way it used to 30 or 40 years ago.

The UK founded the Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA), with a hub at London’s science-focused Imperial College in 2016, while Germany established the Cyber Innovation Hub in 2017 to enable closer collaboration between startups and the military. In June, NATO became the latest military organisation to announce plans for an accelerator programme and a $1bn fund to invest in startups.

“Innovation doesn’t come from within the defence sector the way it used to 30 or 40 years ago. Innovation has shifted to a place where we are no longer present, so we are reconnecting to that,” says David van Weel, NATO’s assistant secretary-general for emerging security challenges.

“The UK has already fallen behind in areas like AI, hypersonic and automated weapons. We manage the risk to the public purse while China and Russia, even Turkey have made a landgrab for these technologies and made huge progress,” says Adrian Holt, head of defence at Capita Consulting, who was a founding member of the UK’s JHub, the joint forces’ innovation hub.

AI, autonomous vehicles and weapons, quantum technologies, robotics and even human augmentation are all areas that western military establishments are keen to catch up on.

And it's not just a case of building better drones and bombs. Cyberwarfare has completely redrawn the concept of the 'frontier'.

“National defence has become a much greyer area in the digital realm. It is not a matter of having a strong army, it is also about making sure your electric grid and transport system are secure,” says Guillaume Benhamou, CEO at Ace Capital Partners, which focuses on investing in cybersecurity startups.

Why has the military lost its technical edge?

“One of the problems is the way that defence contracting works. The Department of Defence tends to specify what they want built, rather than sharing the problem that they want solved,” says Nelson. As much as anything else, the Hacking for Defence programme is helping accustom the military to a more collaborative, Silicon Valley-style open innovation model, he says.

There is so much friction in getting a deal through — I can’t imagine a group of youngsters in Shoreditch wanting to put themselves through that.

Procurement rules are also often set in a way that rules out working with startups. A Ministry of Defence (MoD) tender might, for example, ask for evidence of prior work with defence, something that a young startup would struggle to provide, says Holt. There can be onerous clauses around liability and ownership of intellectual property that startups can struggle with. Many of these are actually negotiable, says Holt. “But at the point of submitting a bid it can seem really black and white.”

It can be tough even for big defence contractors like Capita to negotiate deals, he says. “Sometimes there is so much friction in getting a deal through, it's tough even within a large corporate. I can’t imagine a group of youngsters in Shoreditch wanting to put themselves through that. There are easier clients to sell to.”

It can also be tricky to develop technology for the military amid a culture of secrecy. Guerin says when they first started to develop their AI for military use, the French military would not specify exactly what objects or locations they wanted to use it for.

This was problematic, says Guerin, because AI doesn’t work very well on launch but needs extensive training and correction in order to calibrate it correctly.

“We had to brute force the training and take some guesses. We thought, they're the military so I don’t think they are looking at Luxembourg. We trained it on all the Russian and Chinese aircraft and ships and all the bases we knew of. We may have missed a few secret ones but it was enough to get the system trained,” says Guerin. It worked for Preligens in the end, but a startup less focused on military customers might not have bothered.

Startups — and investors — don’t want to build bombs

It isn’t worth beating around the bush about this — defence departments also have a big image problem in the tech ecosystem. In an era where people are increasingly seeking purpose-driven jobs, engineering talent shies away from startups developing bombs and spyware. This became obvious in 2018 when Google faced a rebellion among its employees over Project Maven, a project to use AI to improve the targeting of drone strikes.

14 out of 15 people US military intelligence personnel I spoke to asked if my employees were happy working with a company that does defence work.

It’s become a big concern, particularly in the US. Guerin recalls a startup speed dating event he attended before the pandemic, organised by the French embassy in Washington DC.

“I met some US intelligence personnel and out of the 15 people I spoke to, 14 of them started the conversation by asking if my employees were happy working with a company that does defence work. It gives you an idea of how strong that concern is in the US,” he says.

This attitude affects investors as well. Preligens recently raised €20m — one of the biggest recent rounds for a military tech startup. Investors are happier giving half a billion dollars to a quick grocery delivery startup than they are to invest a few million in a tech company connected to the defence sector.

“Defence suffers from the challenge of whether it's in line with the ESG mandates that many LPs and GPs have,” says Benhamou at Ace Capital Partners. “If you are a generalist VC it is easier to just avoid it.”

“Our view is that defence does fit the ESG remit but there is some complexity to that. We avoid anything that is attack-oriented and avoid any lethal systems,” he adds.

Europe’s advantage?

Startups that can work around these concerns, however, could seize a big advantage, says Guerin. It is one area where European companies can move ahead of US competitors. Guerin says the majority of Preligens employees are actually highly motivated to help the armed forces and military intelligence. It's a combination of patriotism and wanting to work with the tough and interesting problems that military customers can provide.

“If we were to drop the military work tomorrow, I think half of our workforce would leave,” Guerin says.

Ace, too, is finding a relatively open field. It's in the process of completing a new €200m fund to focus expected to close this autumn, and Benhamou says there is scope for raising a fund two to three times as big as this to meet the demand for cybersecurity investments.

The military often deals in large cheques, £500k plus.

The other good news is that, although getting a contract with a defence department is tough, once you're in, the cheques are big.

“The military often deals in large cheques, £500k plus. If a deal is less than that it can be a struggle to get people’s attention on it,” say Holt.

And once you are in with one defence department, sales to other Allied militaries tend to follow.

“When you do have something approved by one NATO country, everyone else seems to adopt it too,” says Guerins.

******

Maija Palmer is Sifted’s innovation editor. She covers deeptech and corporate innovation, and tweets from @maijapalmer

In the following three parts of this series, we'll take a deeper dive into the European startups working on some of the hottest areas of military tech: human augmentation, drones and AI/data.