From the monarchs of yore to today’s global CEOs — leaders have always had succession on their minds. Even more so today; the average CEO is only around for five years.

Yet for many VCs, the topic remains taboo.

As the industry expands — funding for European startups quadrupled from 2017 to 2022 to reach $94bn — VCs will have to start succession planning if they want to keep their firms running for another 40, 50 or even 100 years. Some older US VC firms have already transferred leadership successfully, but many European firms still haven't thought about who will take the reins when the original partners check out.

Last year, more than 50 new funds were launched in Europe — some by former investors at other VCs. According to William Prendergast, founder of Frontline VC, this is a sign of poor succession planning at bigger firms.

“A lot of these people who are starting their own firms are just highly entrepreneurial, so they want to do their thing anyway. But I suspect that in more than half of those cases, people didn't have the opportunities within their own firms.”

Why VCs don’t want to think about succession

The VC industry's struggle with succession is baked into how firms are structured. Firms are generally founded by a small handful of individuals, and their success rides on these individuals’ ability to fundraise, close deals and support founders.

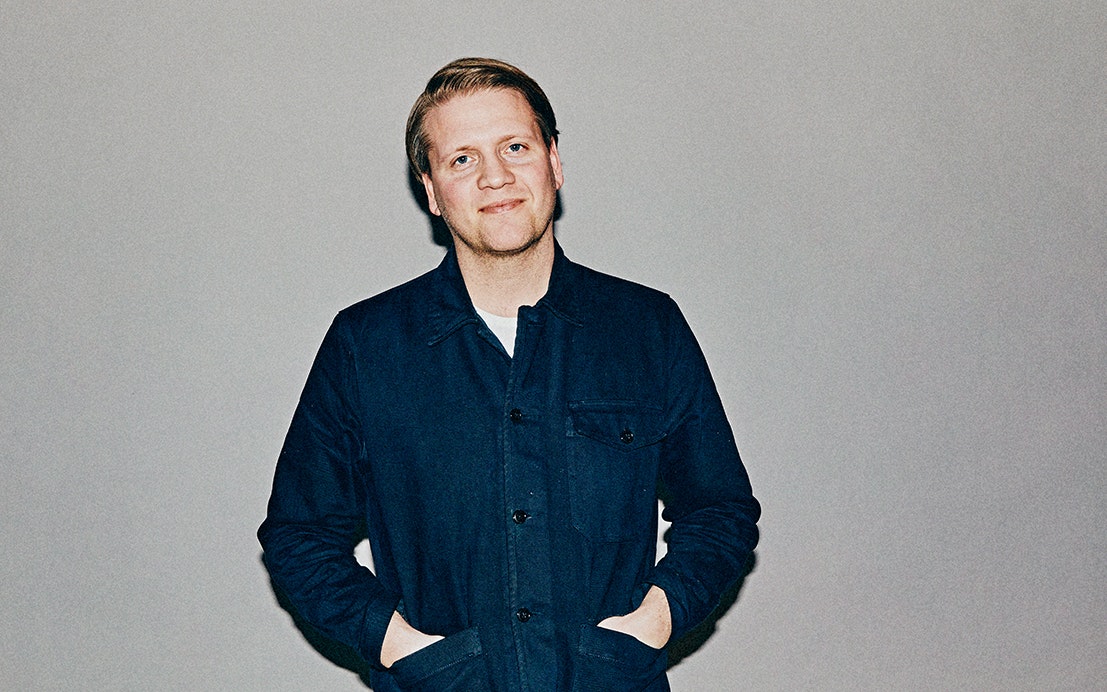

“Historically, venture partners have been a bunch of cowboys — they've been doing their own thing, doing their own deals, sitting on their own boards, selling the companies and not focusing on building firms that can last,” says Linus Dahg, who just took the role of CEO/ managing partner at Nordic VC Inventure.

There often simply isn’t room for every investor at a firm to become a partner. Fund profits — or carry — are distributed among partners. More partners equals less carry for each. Associates at most VCs don’t receive carry, but partners may get 10-20% vested over six to ten years.

Then there can be conflicting messages from LPs (the investors in the funds) about succession. They want firms to think about it, but they also want stability and long-term relationships with the investors running the show.

“The LPs are doing a lot of research into the fund before investing, both doing interviews on an individual and group level. They need to be convinced that the group can work together for the 10 to 12 years the fund is running,” an investor who wants to stay anonymous tells Sifted.

And in many cases, there are specific clauses in the contract between LP and VC that state that if some of the key people at the VC leave the firm, the LP can withdraw funds.

Why succession is more relevant now — and the risks of not planning for it

That model of “cowboy VCs” might have worked when VC was a much younger industry and there was less competition. Now there's plenty: a record 314 European VC funds reached a final close in 2021, according to Invest Europe, an industry body.

VCs are hiring more junior investment staff to do research and diligence on deals with the aim of winning more, and better, deals. And to hire the best people, firms need to be able to motivate them with a plan for how they can work their way up. If not, they risk people leaving to found potential competitor firms.

“If you don't manage to build a long-term plan for people at the firm, they're going to leave to set up something by themselves or join another existing VC where they get more responsibility and a better chance to have a bigger impact,” says Inventure’s Dahg.

That can also be difficult when it can take several fund cycles for new partners to get a significant stake in the firm. Insiders say investors will have to go through at least two to three funds to gain a large stake.

“If you don't have a succession plan, or it's not clear how people can progress up, the incentive you create is for everybody to eat what you kill — I'm going to do my deals, I'm going to be successful and then I'll figure out what I do afterwards,” Prendergast says.

Succession successfully?

In Europe, where even the most famous and successful firms — the Northzones and Baldertons of the world — are just above two decades old, there haven’t been too many speedbumps yet.

In the US, firms like Sequoia and Benchmark have gone through the process already. Sequoia, for example, has been through several senior leadership transitions in its half-century history. Last year, global managing director Doug Leone named Reolof Botha as his successor.

Phoenix Court Group, which early-stage VC LocalGlobe sits under, is one of the more high-profile examples of succession in Europe. Founder Robin Klein set up LocalGlobe in 2015 with his son Saul and transferred leadership to Saul in 2018.

“If you view venture capital like a musical that goes up in the West End and runs for a season, it's not designed to be sustainable,” Saul Klein says.

“A venture capital fund normally has a 10-year life, and I think a lot of people starting funds think over one or maybe two fund cycles. So they don't end up investing for the long term, either in developing their people or developing governance or developing succession planning.”

In 2021, LocalGlobe set up an internal project called “next gen”.

“This is a four-year plan to build leadership capabilities within the business so that the next generation of leadership will be prepared to assume more senior roles within that timeframe. And that's something we've been very transparent about,” Klein says.

According to him, this doesn’t just involve the VC team but also people in operations at LocalGlobe.

“Anyone in the firm should have the ability over time to be able to manage the business, whatever level they come in at, and whether they're on the investment side or the operation side. It is probably very different from other firms where the leadership is typically always on the investment side and the operation side is very much like the back office,” Klein says.

Whatever way the succession is planned, this is one topic that won’t go away anytime soon in the corridors of most VC offices.