Even though we’re nowhere near the December window for copious VC predictions on the future ahead, I’m going to go out on a limb and say VC is no longer a game of prediction and pattern matching. "VC by CRM" is dead. For funds to really stand the test of time, investors need to generate insights.

Is all the previous data amassed of any use anymore?

Previously, I’ve argued that the private asset classes were steadily morphing into their public-market counterparts owing to their shared quest of amassing as much data as possible. In recent years, VC has been an exercise in accruing data, creating as much information asymmetry as possible between you and your peers. This was largely possible due to the steady consistency of enterprise SaaS businesses able to complete the fabled path to the IPO promised land, giving far greater visibility on what consistent and top-decile SaaS performance looks like.

However, the combination of shuttered public markets and the seismic recent developments in applied AI has caused considerable soul searching in VC. The question now is whether the patterns that investors were previously reliant on for determining investment decisions are still relevant as we enter a new supercycle.

One huge differentiation in this era is the number of founders who are coming from academia rather than industry. For instance, of the eight researchers cited in the revolutionary 2017 AI paper "Attention is all you need", six have subsequently left academia to build. The volume of academic founders hasn’t been seen for the last decade, and if I were to draw a historical parallel, it would be the early days of Google.

This is a wave of deeply technical people who are raising significant sums of capital, which has left 2021’s obsession with second-time founders looking quickly antiquated. It was entirely purposeful that Sam Altman chose to speak at UCL and a number of other universities on OpenAI’s recent global tour. That is where the concentration of future founding talent lies.

The pace of innovation also means that VCs are having to radically change their methods of assessment for new deals. It’s one thing for investors to say they come to an investment with "a prepared mind", but the reality is most people had no idea what autonomous agents or transformers were until six months ago. The traditional frameworks of underwriting a Series A deal at $1m of ARR do not apply here. It’s particularly murky for B2B investors, who are still waiting with great intensity to see whether CEO enthusiasm for AI on earnings calls translates to enterprise spend.

The biggest existential risk to VCs is the return of capital efficiency. I’m fundamentally of the view that AI efficiency and the resultant productivity gains will accrue to the end user. The optimist in me believes that companies won’t be able to capture productivity gains, and as we've seen time and time again technological advancement results in deflationary pressure for the end user. AI-enabled productivity gains are already evident with Copilot for engineering teams, and we’re seeing the same is true for people-facing roles such as sales and customer service. If we leave aside the $100m+ rounds for foundational models for now, this cohort of infrastructure and application founders are showing that they need far less cash and can accept far less dilution.

The lean fund era

So what does this mean for VC funds? If this is the new era of lean startups, it means an era of lean funds likely beckons. The mega-funds are already faltering. It’s hard to understand the logic of an early-stage fund raising $1bn+ without an opportunities arm; the days of deploying $400m a year into Series A in Europe look firmly in the rearview mirror. Moreover, if I’m wrong and VC morphs from the lifestyle subsidy model of 2015 to the compute subsidy model of 2023, there's going to be a rapidly diminishing field of funds left in the game. The barbell of venture will be purely a function of cheque size — it’s a small universe of 20-30 funds who can write the $100m cheques required at the foundational level.

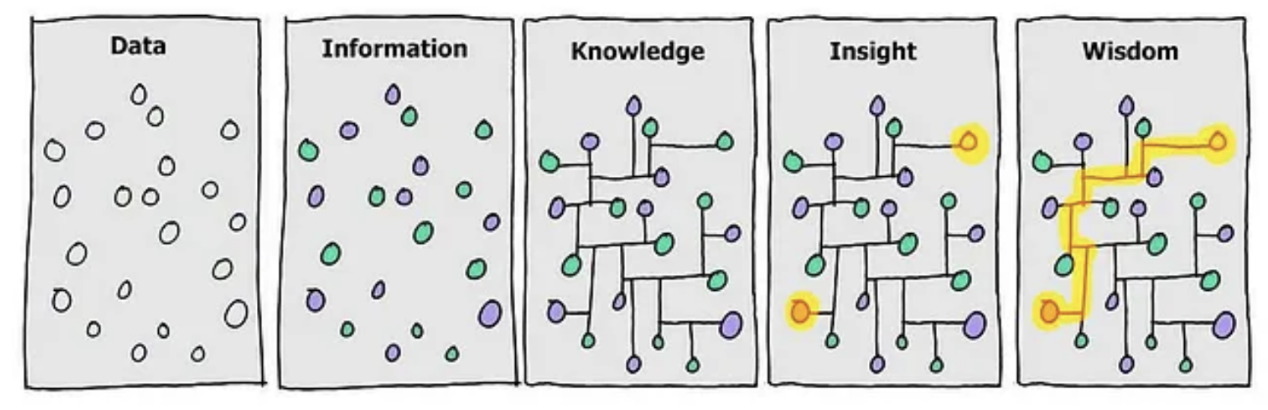

So how do us mere mortals stay relevant? Fundamentally we need to think differently about what purpose data collection is serving, which will enable us to move from producing predictions to producing insights. Prediction is entirely a function of data, there is no subjectivity involved. Hence the recurring message from Microsoft’s Satya Nadella that every AI app starts with data; the foundation and defensibility of AI is data. In contrast, insight is a question of judgment and far more contextual awareness is needed to orchestrate judgment.

So for example, when the iPhone was first launched, the obvious prediction to make was to focus on iOS, category-specific apps. Whereas an insight would involve judging that the combination of apps and cheap access to location services would make it possible to bring about the end of taxi monopolies. Insight allows investors to move from the primary level of inference to apply the secondary and the tertiary impacts of technological change.

As LPs look at the dumpster fire of most portfolios, investors won’t be rewarded for sticking within the comfortable confidence interval. They’ll need to see VCs who are willing to move further out the distribution.