Of the 116 venture capital-backed European companies worth more than $1bn, only four are university spinouts: Collibra, Exscientia, MindMaze and Oxford Nanopore.

That’s a poor rate for a continent that says it wants to lead the global tech race in the 21st century and turn its cutting-edge research into world-beating companies.

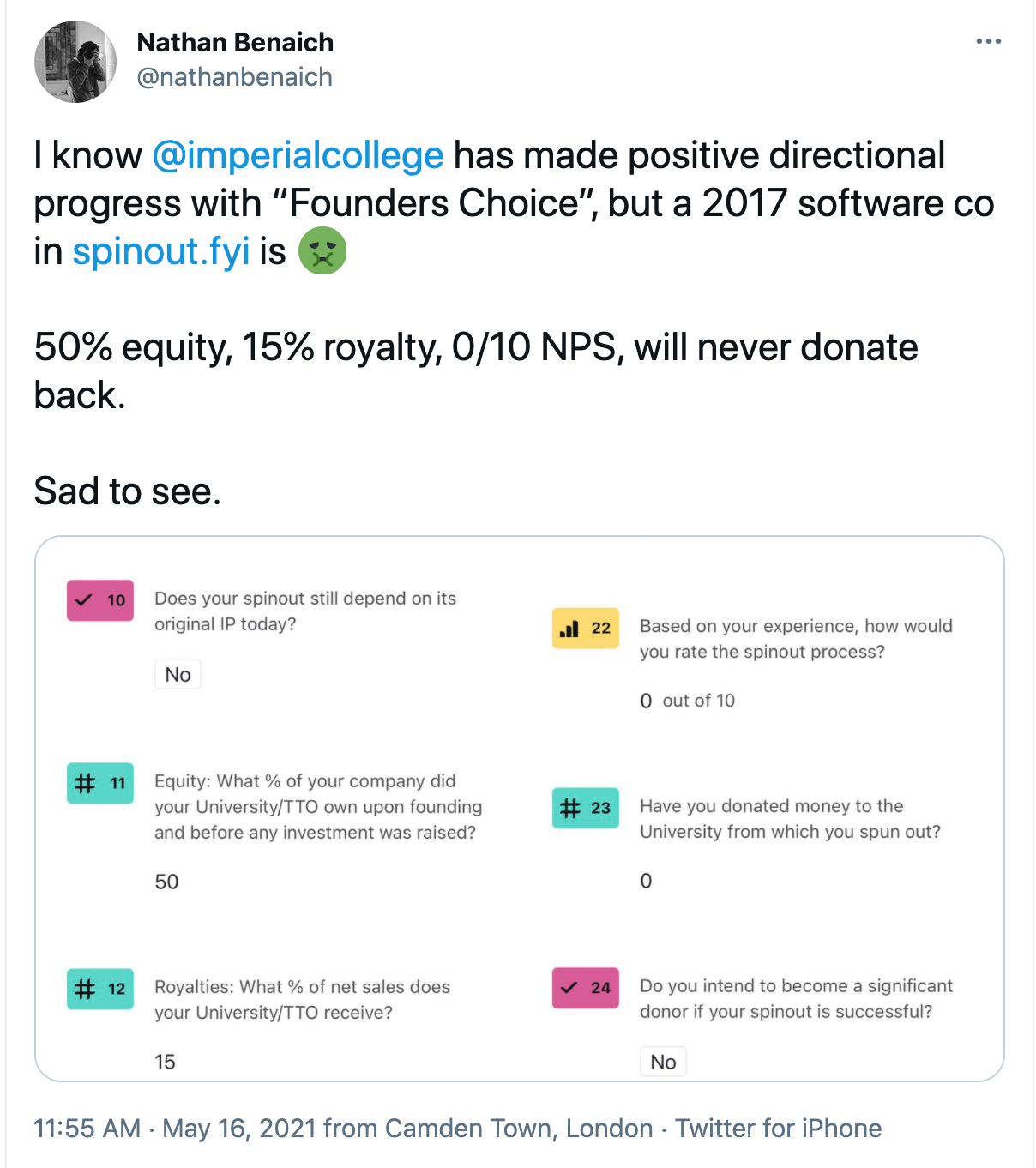

For venture capitalists, the problem is clear: universities are too greedy and short termist, with their tech transfer offices often insisting on taking between a 25% and 50% stake in any spinout project.

This then makes it extremely hard for them to raise outside capital — so the projects flounder.

“I can’t bring a deal with 50% university ownership to a mainstream VC,” says Jamie Macfarlane founder and CEO of the Creator Fund, which is focused on investments in university spinout companies through a network of scouts at 25 UK universities and three Swedish ones.

“I saw a company recently where the university had a substantial chunk of the equity and the founder had just 30% — it just wasn’t a deal worth doing,” he adds.

Nathan Benaich, founder of Air Street Capital, a technology and life science VC, calls anything above a 30% university holding “criminal”. He told Sifted last month that he wouldn't do a deal above this level.

But tech transfer offices take a different view, saying that it’s the VCs who are often the greedy short termist ones who on top of that do not always appreciate the good work their offices do.

So who is right? Do these offices need an overhaul to help European tech lead the world in the decades to come?

VC view: no equity, no motivation

Macfarlane says that having founders start with a relatively low equity holding leaves them with so little stake in the company after the first few seed and Series A rounds that they will not be motivated to continue.

Each early-stage round typically dilutes shareholders by around 20% to 30%, so a founder starting with a 30% share will find themselves rapidly diluted down before even reaching the scaleup stages of funding.

This chart from Osage University Partners shows how a lead founder’s 30% stake shrinks down to 12% by the time of the company’s Series C round.

“VCs want to back hyper-motivated founding teams and so they want founders to have the lion's share of equity,” says Macfarlane. When you are only left with a tiny equity holding, Macfarlane says, a founder starts seeing an attractive job offer as a preferable alternative to the insane hours of building a startup.

Yet a 50% stake can be relatively standard. Some universities like Cambridge, UCL and Imperial College will take less, but many of the universities in the north of England, like Nottingham, Sheffield, Leeds and Warwick, tend to take a 50% stake. Imperial College, for example, has a "Founders Choice" option, where academic entrepreneurs who only want minimal help from the university only need to give the university a 5% to 10% equity stake in their startup. If the founders want the university to be more involved in setting up the company and developing the business plan, the split would be 50/50 between founders and university.

These universities, located in regions that the UK government wants to “level up” and regenerate, have the potential to create a lot of high-value jobs if they made it easier to commercialise their research, Macfarlane points out.

Macfarlane would like to see university ownership capped at 5%. Benaich is even more extreme, recommending the university share be between 1% to 5%, or for the university to take a 1% royalty on net sales, or 1% of the exit value of the business if it is bought or it launches on the stock market. But not all of these together.

Could the tech transfer system be changed?

Tony Raven, chief executive of Cambridge Enterprise, Cambridge University’s technology transfer organisation, isn’t sure that the university tech transfer system could be reformed in the way that Macfarlane and Benaich suggest.

He says that the idea of capping ownership at 5% would not be right because it would not take into account the very different circumstances for each company. “A copy and paste, one-size-fits-all approach won’t work,” he tells Sifted.

A copy and paste, one-size-fits-all approach won’t work.

Many people try to learn the Cambridge model of taking a little less equity, he says, but find that it doesn’t work for their particular context. Even Cambridge doesn’t have a precise formula, but tries to “be fair and reasonable and aim for the path of least discomfort.”

“You have so many different cases from the professor who has devoted his whole life to this research to someone who has joined an already-established research group and benefited from work they were already doing,” he tells Sifted.

Raven says Cambridge Enterprise tries to strike a balance between recognising the people who put in the years of foundational research to create the invention and those who are turning it forward into a company. You may have researchers who don’t want to join the company, but who have been fundamental to the development of the product. In these cases the university might take a larger equity stake in the company to let them share in the rewards.

“The last thing you want is research groups who won’t talk to a founder because they will walk away with all the rewards for the years of research,” says Raven.

The problem is, however, that the highly customised approach makes the system very opaque. No one really knows what a standard deal looks like. Air Street Capital is trying to fill in the knowledge gap by crowdsourcing information about the deal terms different universities offer. (You can take part here.)

Smaller slice, bigger pie?

VCs argue that universities need to stop getting hung up on protecting everyone's rights and allow spinouts to grow bigger.

Stanford and its big windfall from Google is an example of how a successful spinout can benefit a university. Stanford owned the IP for Google’s central PageRank algorithm but licenced it to the company for some 1.8m in shares. This was a tiny holding, but selling just 10% of the shares at the time of the Google IPO brought in $336m for the university, which was a record sum for university tech transfer back in 2004.

15% of $626m is a lot more than 50% of something that isn’t going anywhere.

A local — and more recent — example is Bristol University spinout Ziylo, a biotech company developing glucose-responsive insulin, which was bought by Novo Nordisk for £626m in 2018.

Bristol University held a 15% stake in the company — higher than Stanford’s stake in Google, but far lower than the 50% that many universities would take.

“But 15% of $626m is a lot more than 50% of something that isn’t going anywhere. We need these lessons in the UK,” says Macfarlane.

In the case of the two UK spinout companies that have become unicorns, the parent universities stakes are smaller still. Oxford University owns only around 0.8% of Oxford Nanopore, but this stake is worth £19.2m. Meanwhile the University of Dundee owns a 6% stake in AI-drug discovery company Exscientia, which is worth £52.1m.

Should you simply circumvent the tech transfer office?

One way around university spinout issues is simply to circumvent the tech transfer office and work only with companies founded by PhD students. As long as the students aren’t working with a professor at the university, the university doesn’t own any of the IP.

This is one of the reasons the Creator Fund works mainly with students, rather than professor-founded companies.

Riam Kanso, founder and CEO of Conception, which advises students on how to become entrepreneurs, also often suggests that they simply try to work outside of the university tech transfer system.

In some countries, like Sweden and Italy, the so-called “professor’s privilege” means that academics own all the IP rights to their innovations, not the university. That means that in principle they don’t need to give their universities any stake at all.

But, says Raven, it's not clear that this is always the best option for would-be founders. Cambridge University in fact had the same policy of academics owning their own IP until 2005. Then the faculty voted overwhelmingly to change the policy, with the university taking ownership of the IP in return for more support in commercialising it. Even now, it is possible to go it alone if you want — but few take up the option.

No inventor is obliged to work with us. But less than 1% [choose to go it alone].

“No inventor is obliged to work with us. There are those who don’t want Cambridge’s help, who know exactly what they are doing and can draw up a business plan on the back of an envelope and get it funded. But it is less than 1% of cases,” says Raven.

Tech transfer offices do provide would-be entrepreneurs with valuable help in setting up the company, honing their pitch and even meeting investors. Many have their own venture funds and can invest the first seed money into the ventures.

“I was pleasantly surprised with how helpful TU Delft was. They helped us with pitches, and connected us with VCs,” says Simon Gröblacher, CEO and cofounder of QphoX, the quantum modem company that recently spun out of Delft University. To be fair, though, Delft University hasn’t taken a large “free” equity share in QPhoX, but invested alongside other investors.

Are universities the real problem?

An experienced tech transfer office can also help push back on onerous VC requests.

One VC that Raven dealt with asked the spinout company for a 12x liquidation preference (meaning that in case the company was liquidated the VC would get a 12x multiple of their original investment back before any other investors got their money).

“We had to say that was just not going to happen,” Raven says.

The majority of tech transfer offices lose money.

Raven counters the complaints about tech transfer offices by saying that it is not the university holdings that are the problem, but the ferocious rate at which founders’ stakes are diluted by investors.

“Many of our early Cambridge entrepreneurs built successful companies and made very little money. When you ask them if they will do it again, they say ‘why should I? I worked very hard and a lot of people made money off me’,” says Raven.

A good example was UCL-spinout BioVex, founded in 1999 and sold to Amgen for $1bn 12 years later. Cofounder David Latchman famously revealed that he netted just $709 from the deal, having had his original 25% stake diluted down to fractions of a percentage over the years. UCL’s share was not much higher than Latchman’s however — VC investors owned around 90% of the company.

Unlike venture capitalists, notes Raven, university tech transfer offices are rarely in it for the money. They are charities that would tend to recycle any profits back into research. “Usually it's more a case of the directive being that at least don’t lose money — and the majority of tech transfer offices lose money.”