The good news? Britain’s deeptech sector is growing.

The bad news? The UK doesn’t have enough energy infrastructure to support these energy-hungry startups.

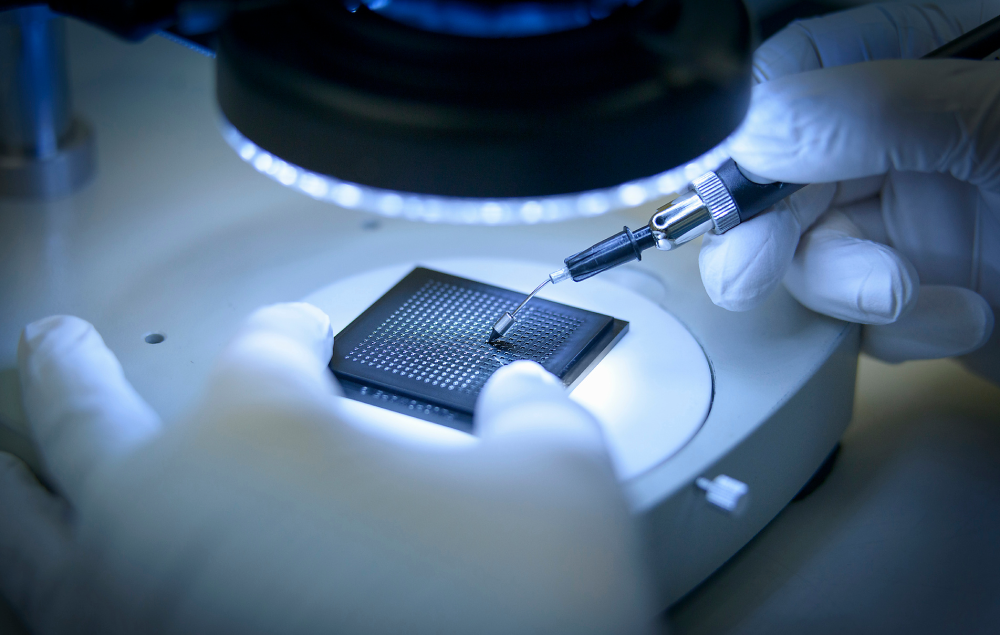

Founders building businesses in areas like AI, semiconductors and quantum, which require lots of data centre capacity and power, tell Sifted they are struggling with Britain’s old electricity grid, power generation shortages and lack of understanding from local authorities.

Simon Thomas, CEO and cofounder of semiconductor startup Paragraf, says his company “moved into its second facility knowing full well that the local infrastructure was unable to supply the required power without a significant upgrade to the connection with the main grid”. It took them a year and £1m to achieve connectivity.

That amount might seem tiny by comparison with the £2.5bn for expanding its UK data centres announced by Microsoft on Thursday, but it’s an obstacle for growth, Thomas says.

“After significant requests for support we eventually had to pay the significant cost ourselves to ensure our production capacity expansion, and hence overall growth of the company could happen on time,” he explains. “Such unnecessary hurdles are detrimental to the successful scaling of a manufacturing business, drawing vital resources away from core, value-adding growth activities.”

The problem is most acute in London where demand is highest. Unless power constraints are tackled, tech startups may be forced to relocate to other parts of the country where they can meet their energy demands. Some might decide to hire cloud providers based in the US, moving their data stateside. And UK hubs may struggle to retain businesses as they grow.

“Currently what we have is not helping us meet that demand. The UK has always been a great place to start a business but, of course, if a startup relies heavily on data, on AI machine learning, it will require a lot of power. We do need to see a move from government,” says Luisa Cardani, head of data centres at techUK, an umbrella lobby group for British tech companies.

Huge demand

Generating the power is just one of many issues that need to be addressed, says Mark Turner, chief commercial officer at Pulsant, which operates 12 data centres across the UK.

Most data centres in the UK are more than 10 years old, and unable to deliver the power density required by startups working on cutting-edge tech. Existing data centres will need to be improved to increase the power they can deliver to a single footprint, he says, and enhance their cooling capabilities by, for instance, delivering liquid coolant directly to the chips.

“Suddenly, this new wave of AI applications, where people want water cooling in your free cooling data centre,” Turner says, referring to a new energy-efficient technique. “There’s quite a challenge there in that the sites are not designed for that but the need is real.”

He says that he was approached last summer by a large cloud service provider looking for 25 megawatts of energy in London — enough to supply the average power requirement for around 50k homes for an hour.

“All that illustrates to me, the amount of capacity that is being planned for the future and the amount that will need to be built is incredible, and is being driven by AI, which is a huge part of it.”

Securing suitable sites, however, is a nightmare all over the UK, Turner says, because lots of places where power is produced from renewable sources turn out not to be well connected to the grid.

A solar power business located in Hull, in the north-eastern coast of England, recently had to switch off its energy generation on sunny days because at the moment “all it is doing is servicing the local port and there’s no off-take onto the grid”, says David Bloom, founder of Goldacre, a London-based VC firm, and chairman of London-based Kao Data, a developer and operator of high-performance data centres. That means the extra energy it was producing wasn’t actually being used.

Zombie projects

Concerns around securing power are running so high that businesses were putting in a request for power way in advance and before knowing their exact energy demands for certain — clogging the system even more.

Turner says a few of Pulsant’s data centres in the south of England which are operating at nearly full capacity have applied to the regulator for more power, but were told “we’ve got to wait five to seven years”.

In a bid to tackle this problem, Ofgem, the energy regulator for Great Britain, has announced a reform of its first-come, first-served system to allocate power to businesses. Its new policy, which came into force on Monday, aims to clear “zombie projects” by ending stalled projects that are blocking the queue for high-voltage transmission lines. Ofgem’s reform “is very welcome” but “it’s not enough”, Cardani from techUK says.

“It’s worth noting that any major changes to the national grid will only likely happen once we have an outcome of the national election, because it would require a significant investment and entirely new budgets,” she says. “We need to properly digitalise the national grid in order to pinpoint how to make efficiencies.”

A spokesperson for Ofgem says Britain requires an unprecedented amount of new energy infrastructure, and that UK regulation “continues to evolve rapidly to ensure we deliver this on time and at the least cost to consumers”.

Building headaches

Builders of data centres have another wish for the UK government: a more streamlined, better informed planning process for building new sites.

Earlier this month, Anthony Crean, a former planning lawyer-turned-developer, blamed “green belt theology” for a local council decision to reject his planning application to build Britain’s largest hyperscale data centre, financed by £2.5bn from an undisclosed US tech firm. The site would have potentially served deeptech companies.

Bloom wants the UK government to provide local authorities, normally unfamiliar with the technicalities of these facilities, with guidance on what they should require from applicants seeking permission to build data centres, including on power consumption and noise. He says most local authorities are familiar with office, residential and even logistics planning, but data centres are a new thing.

To illustrate this lack of understanding, Bloom recalls a meeting at a local council in the UK, where they were proposing a building. “I gave an overview of data centres and one of the council members came up to me afterwards and said: ‘Tell me, why in America do they call them databases, whereas here in the UK we call them data centres?’ And I say: ‘That’s just because they are two different things.’”

A multi-mega-watt data centre may employ 15 or 20 people rather than the hundreds that some local authorities would like to see in planning permission applications, Turner says, “so it doesn’t get the instant ‘this is high value for our region’.”

“And if there’s a housing estate that needs to be built and there’s not enough power for that and the data centre, the data centre is always going to lose out.”