Melting ice in the Arctic is one of the most visible — and worrying — signs of our rapidly changing climate.

Over the past 30 years, the oldest and thickest parts of the ice in the region have shrunk by 95%. The ramifications are widespread: ice is crucial for reflecting heat back into the atmosphere, so if it melts, temperatures rise. Melting ice also contributes to rising sea levels.

Preventing emissions like CO2 from entering the atmosphere helps to slow the melting — but some companies are taking a more direct approach. Welsh startup Real Ice, which took part in a United Nations “for Tomorrow” accelerator, is working on technology that it says could refreeze parts of the Arctic ice and boost its thickness.

“This is ecosystem preservation,” says Andrea Ceccolini, CEO of Real Ice. “We're trying to maintain, at the very least, the ice that we still have, which is roughly four million km² at the end of the summer. And if we can, we would love to restore what it was in the 1980s, which was over seven million km².”

The company is working under time pressure, he adds: “The latest research shows that within the next 10 to 20 years we're going to see the first blue ocean event, where there is no sea ice in the Arctic at the end of the summer period, for the first time in two million years.”

So how do you manually freeze ice?

Real Ice’s technology is based on early research from Arizona State University and the University of Washington. The company started as a volunteer project at Bangor University in north Wales, where graduates got the idea to make the earlier science a reality, before morphing into a startup two years ago.

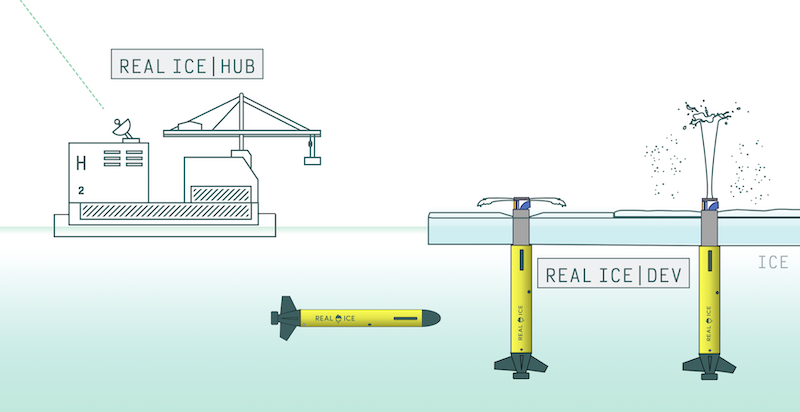

Its tech works by sending out underwater drones which bore holes in the ice from underneath. The drones will be powered by green hydrogen, Ceccolini says, and dispatch from floating platforms.

Through the hole made by the drone, water is pulled from under the ice and sprayed on top of it. Spraying water on the top of the ice removes the layer of snow that settles on it during winter and acts as an insulating layer, preventing the ice from expanding.

“With the snow on it, the ice will struggle to grow much thicker through the winter season,” explains Ceccolini.

Removing the snow and adding water to the surface means a new layer of ice forms — and the overall temperature of the ice block is lowered, allowing its thickness to increase.

Real Ice will spend the next three years working on testing and building prototypes — it’s currently working in conjunction with the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Climate Repair. After that, it will start its first scaled-up exercise, which will cover 100 km² of ice in Canada.

How do you finance it?

So far, Real Ice is bootstrapped. Ceccolini says he hopes that money will open up for Arctic preservation in the same way it has done for protecting other ecosystems. There’s the Amazon Fund, for example — a $1.3bn pot of money funded by countries around the world to protect the Amazon rainforest.

The other funding mechanism Real Ice is looking at is “cooling credits”. They are similar to carbon credits — which are equivalent to a certain amount of carbon emissions avoided or removed from the atmosphere — but, instead of measuring emissions, they measure the cooling potential of a particular intervention.

The cooling credit model is yet to be solidified. The mechanism drew controversy last year when US startup Make Sunsets released reflective sulphur particles into the atmosphere, aiming to reflect sunlight back into space — and hoping to sell credits off the back of it.

Critics said the move had crossed a controversial barrier in the field of geoengineering, without consideration for the wider ramifications. Geoengineering means intervening in the Earth's systems to counteract climate change.

Ceccolini is keen to distance Real Ice’s process from geoengineering. “We are in the geo-mimicking field; we're not spreading chemicals. We're not creating anything that nature hasn't seen before,” he says.

Working with Indigenous communities

The Arctic’s ice is critical not just for its impact on climate change, but also for the communities living in the region. Roughly four million people live in the Arctic and rely on it for fishing, hunting and transportation.

“A large part of the success of what we do will be determined by how well we engage local people living in the Arctic,” says Cian Sherwin, founder and co-CEO of Real Ice. The company runs presentations in schools and other parts of the community in the region.

“Traditional knowledge should be at the centre of our decision-making process. Without it, we couldn't do what we set out to do,” Sherwin says, adding that local knowledge about the geography and character of the land and ice is crucial to the company’s work. “They are the experts.”

Sherwin says Real Ice envisages local communities running re-icing projects themselves, and receiving the income from any credits generated. It could, he says, offer a form of employment and income away from the more extractive industries at work in the Arctic, such as mining and oil exploration.

For now, Real Ice’s work continues: the team has just headed out on another Arctic mission to test the technology.