Last week, Dutch file-sharing company WeTransfer cancelled its IPO. The 13-year-old company was planning to list on Amsterdam’s Euronext exchange at a valuation close to €700m — but pulled out due to “market conditions”.

On January 13, when the IPO was announced, pandemic posterchild Zoom and European tech darling Adyen were down 70% and 30% respectively compared to their pandemic peaks. Things are still no better: shares in Spotify plunged 13% this week, PayPal has lost around $50bn in market value and Meta shares are also down.

Meanwhile, in the private markets, January felt like boom time: the day before WeTransfer announced its intention to list, Checkout.com landed a $1bn round at a $40bn valuation. The day prior, Bolt, Qonto and Back Market each saw record raises.

What’s going on? Will the public market downturn affect startup raises and valuations? And if so, when?

Growth-stage startups most affected

Brent Hoberman, cofounder of firstminute capital and Founders Forum, tells Sifted that “public market turbulence will have the strongest effect on the IPO market and on growth-stage companies”.

Tony Zappala from Highland Europe, who invested in WeTransfer, also thinks growth-stage companies will be the first to feel the pinch. He says: "The cascade will start with hedge funds that invest in both private and public markets and that have been pricing later stage rounds. Those valuations will follow public markets with probably a three-six month delay. That will mean that private market investors who compete will see less price pressure and so it will cascade from there, with Series A investors probably hardly affected."

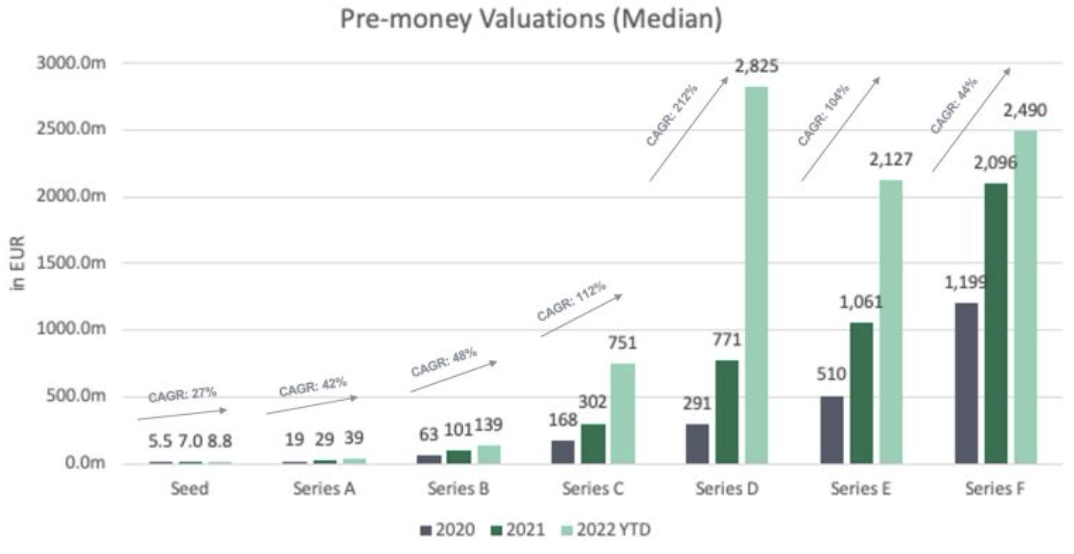

Hussein Kanji from Hoxton Ventures, which saw three portfolio companies — Deliveroo, Darktrace and Babylon Health — go public last year, points to an analysis of PitchBook data by 2150VC that shows that “the valuations of early-stage rounds haven’t gone up nearly as much as later-stage rounds” — and therefore presumably won’t go down as much either.

Record amount of VC capital means that startups will still get funded…

“There’s plenty of capital available to get us through, however long this lasts,” Paul Murphy, partner at Lightspeed, tells Sifted. According to data provider Preqin, dry powder (cash raised but not yet spent) has hit $750bn for VCs and growth-focused PE funds globally.

Hoberman also tells Sifted that due to that huge amount of capital waiting to be deployed in tech, “2022 is still probably the second best year ever to be a founder, after 2021”.

…albeit valuations will probably come down

Still, VCs won’t be immune to public market scepticism. Valuations (unless stock markets rebound) will eventually adjust; the first hints of reduced valuations is already emerging.

“Some funds are making pretty dramatic changes to valuations in rounds we’re currently involved in,” says Murphy. “Companies that got extremely favourable multiples based on revenues or profit — $5bn+ companies — that’s where it will get compressed. You’ll see 100x multiples come down a bit because you’d never get that on the public market.”

Median revenue multiples on the BVP Cloud Index, which tracks high-performing SaaS companies, are down from 18x in September to 10x at the time of writing. Higher interest rates also mean that future cashflows should get more heavily discounted in valuation models.

Nobody will say it is a terrible thing that some froth is taken off

Hoberman tells Sifted: “Clearly, we have been in one of the hottest tech markets since maybe 2000. Nobody will say it is a terrible thing that some froth is taken off.” He believes that “there will be more discipline” and that “people will not value everything as a winner any more”. When asked whether he has himself started to reconsider valuations, he says that “not everyone in Web3 will be a winner, let’s say it that way.”

Kanji, on the other hand, doesn't think private market valuations are going to reflect much-reduced public multiples in their valuations. "I think there is more competition in the private markets to get into those companies,” he says. However, the investment period when funds make new commitments might lengthen from two years back to three to four years, implying a slightly less frantic pace of dealmaking, he adds.

2022 as an IPO year

Most 2022 IPO candidates declined to comment on whether the WeTransfer listing had delayed their IPO plans and if they’d try to stay private longer as a result.

London-based fintech Zopa tells Sifted that it will be ready for an IPO “as early as Q4 2022” and have “a consistent track record of profitability” by then. “But we will not be rushed to make hasty decisions. The size of our recent fundraise means we can be more flexible in our timing for an IPO, so we will carefully evaluate the investment climate at the time.”

UK-based battery startup Britishvolt tells Sifted that “listing on the London Stock Exchange is under constant strategic review by the Britishvolt board".

“I suspect 2022 will be a tough IPO year,” Kanji says. “While people are still trying to figure out what the increased Fed rates mean, it would be unusual to try and take companies out. You are not going to have valuation stability.”

Haakon Overli from Dawn Capital says that while IPOs may be paused for the moment, “markets change quite quickly”. He adds that “an IPO has the advantage of being a marketing event, it crystallises employee options, it provides a route to liquidity for early investors and often — unless you are a private giant — customers feel better about you as a counter party.” When the fear in the market subsides, he believes that “people will dust off their offerings”.

What really went on at WeTransfer

WeTransfer is a profitable company with an annual growth rate of 31% over the past few years. Yet, according to an insider, it failed to attract enough high-quality investors in the lead up to the planned IPO.

There are reasons beyond market mayhem why the offer wasn’t compelling to investors.

For one, the ~6x revenue multiple applied to its 2021 figure “seemed steep” to analysts like Patryk Basiewicz from finnCap. In the absence of a directly comparable public company, Basiewicz averaged revenue multiples of a bespoke reference group made up of collaboration companies (including Atlassian, Teamviewer and Zoom), competitors WeTransfer identified (including Dropbox) and smaller freemium companies for small businesses (including godaddy and wix). WeTransfer’s valuation wasn’t wildly out of range, but it also did not “not leave room for many gains, once IPO-related discounts were accounted for”.

In addition, analysts have concerns about the absence of a protective moat against players like Amazon or Google. “The prospectus did not clearly publish retention and churn data which was a red flag,” Basiewicz tells Sifted.

Katja Staple writes about the business of startups for Sifted