Operations leaders are the unsung workhorses behind many startups. While other C-suite roles are defined based on the work that needs doing, the chief operating officer (COO)’s role is defined in relation to the chief executive officer (CEO).

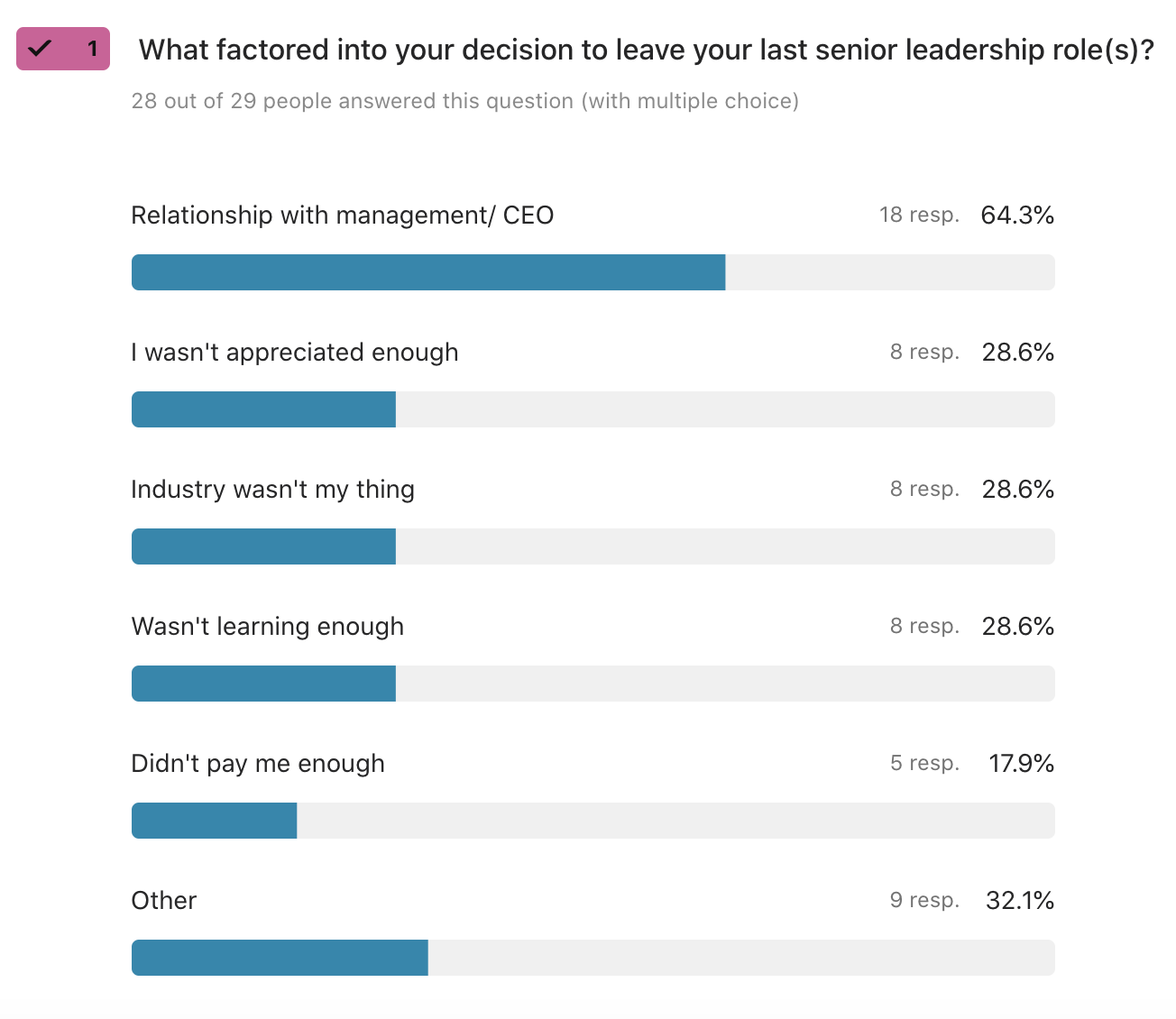

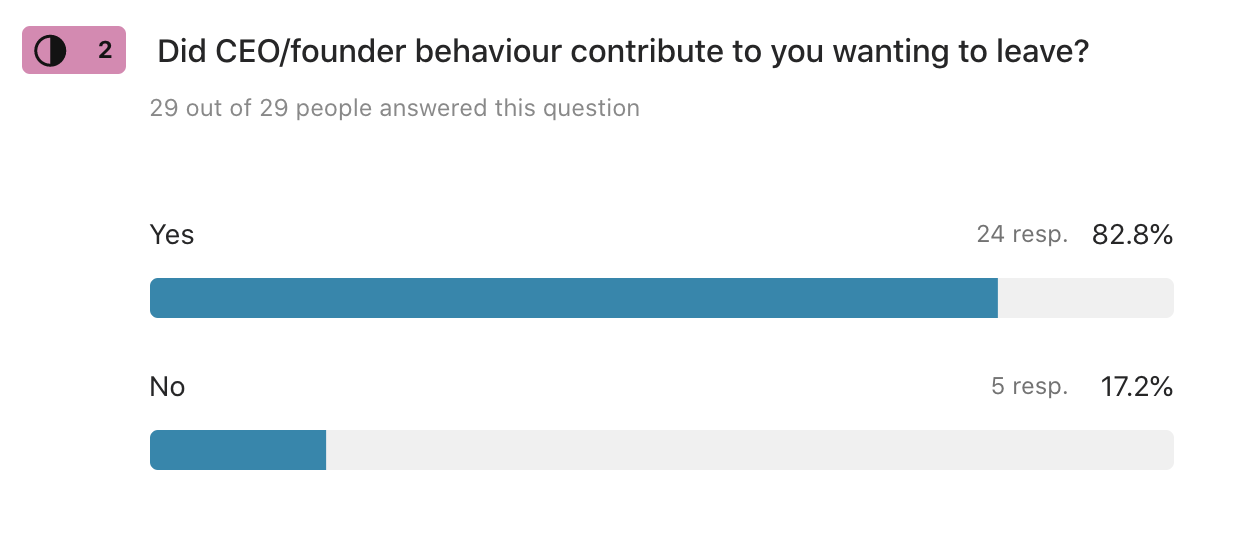

But the COO-CEO dynamic can be a double-edged sword. Based on a spot survey I ran this week, of 29 operations (ops) leaders who’ve recently left roles, over six in 10 cite a leadership team dynamic as the most common factor in their decision to leave their post.

👉 Read: What does a startup COO actually do?

The success of an ops leader is dependent on how well they can work with the CEO, and how much the two roles trust each other to deliver in their respective areas — much more than any other role in the leadership team. Until CEOs can recognise, empower and trust their COO to make decisions and truly lead, they’re limiting their ability to operationalise and scale the company.

Lots of responsibility but (usually) not part of the founding team

COOs are not usually part of the founding team. Only 17% of ops leaders, surveyed by COO community COO Stories in 2020, were founders. Founding teams are very often a CEO/cofounder pair and at a certain point, the founders decide they need to get out of the weeds and hire their own Sheryl Sandberg.

Joining the founding team in such a senior role can be a tricky dynamic to navigate. You’re the third wheel joining two or more people who know each other really well already.

Most people get into startup operations or ‘ops’ in one of two ways. Some work their way up the individual contributor route: the ops manager to head of ops to COO pathway. Quite a few jump ship from a corporate straight into a senior ops role at a startup, as the professional skills you get from corporate training tend to be value-add in a start-up environment.

Unfortunately, it’s often infeasible for an exec to supersede the founder — even when they’re a root cause of the underperformance.

Whether promoted up from an individual contributor or hired from the outside as a non-cofounder COO, the power dynamic is heavily weighted in favour of the founders. As one COO told me: “Unfortunately, it’s often infeasible for an exec to supersede the founder — even when they’re a root cause of the underperformance.”

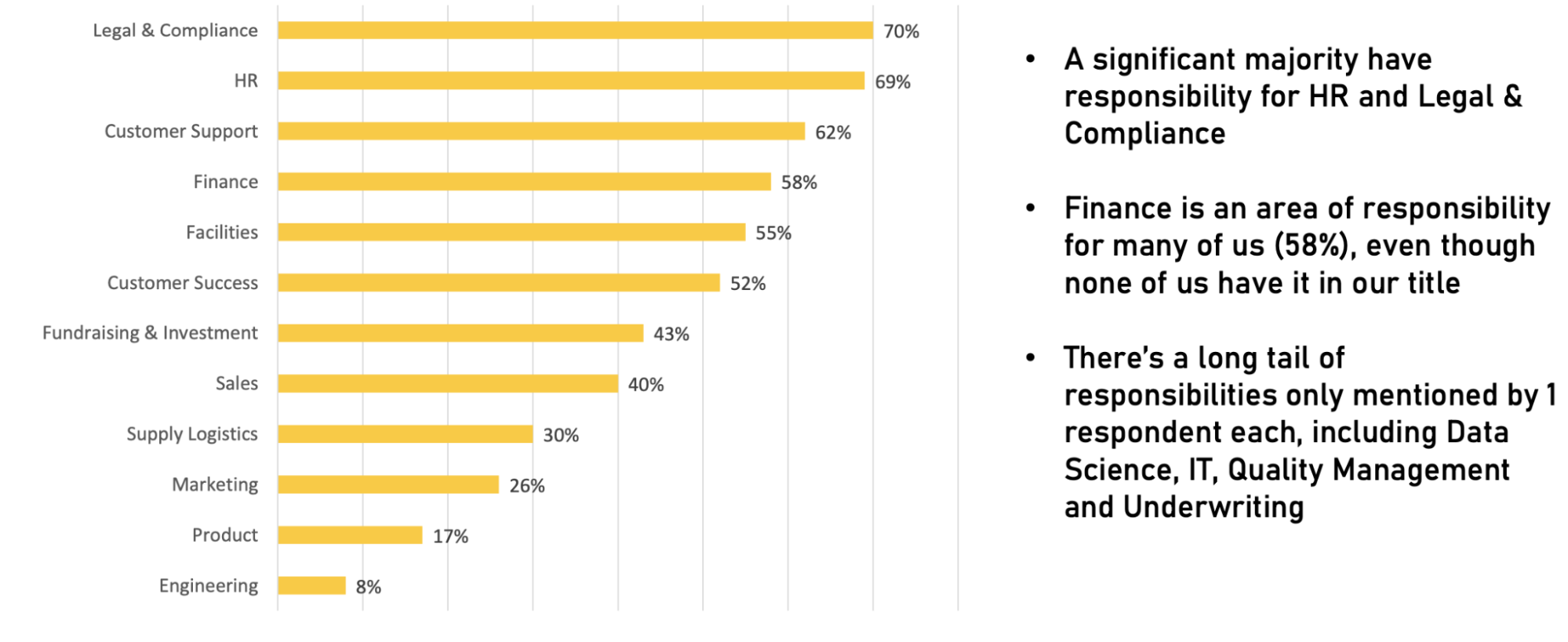

Compare even a small number of COO roles to each other and there’s such divergence in areas of responsibility and ownership that it’s almost impossible to come to a single definition. As second-in-command to the CEO, the COO picks up whatever is needed, helping the CEO cover areas that they and any other cofounders don’t have the capacity or the skill set to deliver on.

COOs need the full support of the CEO to succeed

As the incoming COO, you’re expected to take responsibility like a founder — and to solve problems like a founder.

Before you’ve had a chance to optimise what’s already there, you take on accountability for making the business run smoothly. That can look very similar to what’s expected of a founder: working late to get it done, responding to situations out of hours, and getting creative to solve problems for customers — even if it means being the one taking the complaints or hiring a van to drive something to someone in an emergency. So you can’t help but feel the loyalty and emotional investment of a founder too.

But the effectiveness of a COO can be hampered by CEOs who indulge in a number of unhelpful behaviours. Whether it’s selectively withholding information that would influence operational decision making, agreeing on one thing and doing another, reversing decisions already made and communicated to the team, or even berating COOs publicly for decisions taken without full context. These behaviours leave COOs feeling frustrated and undermined.

One COO friend said recently of leaving a recent role: “The CEO found it very hard to let go and would take meetings without me to move forward an agenda that was different to the one we had agreed in multiple planning meetings.”

Another COO I spoke to was expected to control costs and deliver results, but without any visibility of the financial model or runway, as the CEO kept tight control of both of those things.

How to get it right

So how can companies get the most out of COOs, make them feel valued and empower them to do their best work? Here’s what companies can do to get it right.

From where I’m sitting, the thing that makes people go the extra mile and deliver results for the company is how they’re respected, trusted and backed up by the CEO and other founders.

I asked real-world COOs, “In a perfect world, what could your last CEO have done that would have empowered you?”, and here are their answers to that question:

- Clear boundaries between my work and theirs. Not treading on each others’ toes, and splitting responsibilities based on strengths.

- I think CEOs and COOs need a shared vision for the organisation. Be clear on objectives and expectations. Avoid setting goals that no one in the world could have achieved. Clarify expectations rather than making me guess.

- Ensure senior leaders are aligned on goals and expectations, and invest time staying in sync (at least as much as you spend with more junior hires).

- Fairness — include me around the table that other senior leaders are at, or give me a board seat if all the other leaders have one (particularly if I’m the only non-white man). Pay me equally.

- Enable COOs to build their own relationships with the board/investors/advisors, rather than feeling like these need to be 100% owned by the CEO.

- Considered operations as one of the key functions and a strategic partner of the company instead of a “filler/back office role.” Done the role themselves for a bit so they would have had some appreciation and empathy.

- Being open to outside perspectives, and listened to me. Have seriously considered my input.

- Invested in my personal development. Discuss my career/development/role evolution in a meaningful way. Provided feedback. Had regular communication channels for feedback and support.

- Listened to personal feedback.

- Not bullying publicly or privately. Not criticising team members publicly.

- Not overridden my decisions behind my back.

- Enabled me to hire key roles as we scaled (head of people, office manager).

- Let me do the job I was hired to do. Trust that though I might not be an industry expert, I still know what I’m doing. Trust me to do my job.

News flash: much of this same learning applies to every human everywhere. We all want to be respected, treated fairly and trusted with information so that we can do a good job.

Of course, non-founder COOs do have that one key advantage over their founder peers, which is they can walk away. They can switch companies; trade up roles; start their own thing; or leave tech entirely to become a vegan chef if they want. They can walk. This is the risk that CEOs could do more to understand and accept. Undervalue your COO and they may very well walk away.

Kelsey Traher is COO at Marvel