It has never been harder to raise money as a solo GP.

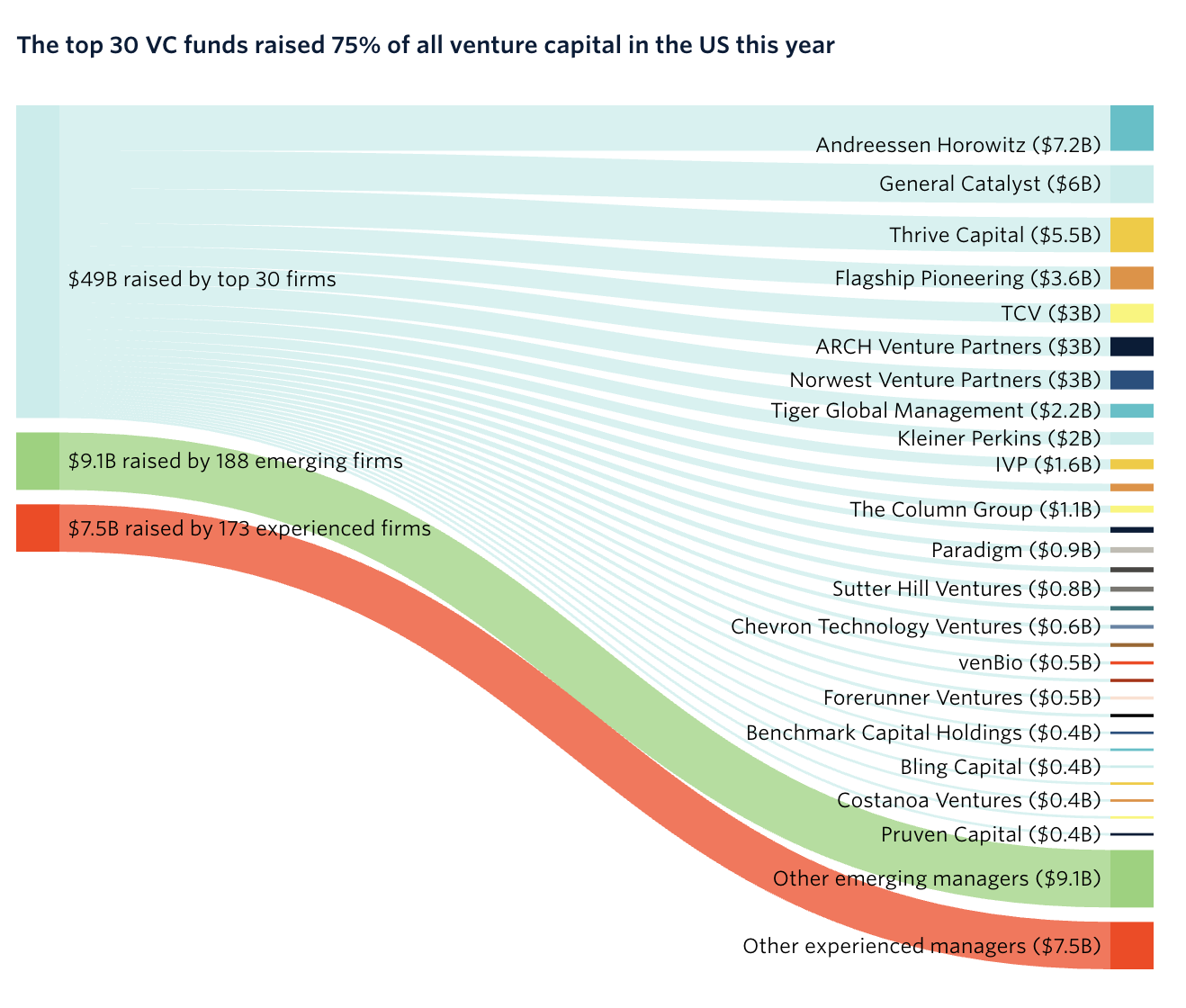

With the IPO market closed and returns for more recent fund vintages looking very poor, investors have fled to “safety”. In 2024 just nine US firms (including names you will probably recognise, like a16z, General Catalyst, Thrive, Tiger Global and Kleiner Perkins) secured well over half of all new capital raised in the US.

Emerging managers raised about 20% of all capital in VC last year — compare this to a peak of ~50% in 2017.

In Europe, the number of VCs announcing new, first-time fund closings plummeted to 34 in 2024; down 50% in two years, from 42 in 2023, and 66 in 2022, according to Sifted.

At the best of times, raising a fund is — as any VC, especially a solo GP, will tell you — a long and painful process. The average time to final close across the entire industry currently sits at 15 months, and that data includes established managers. One solo GP I spoke to recently spent two full years raising their $12.5m first fund, with four separate closes. They interacted with ~1,200 prospective LPs and 58 people eventually invested; about a 5% conversion rate.

But it doesn’t need to be that way.

In fact, most solo GPs should just never raise a fund at all.

Enter: deal-by-deal investing

Raising a fund is not the only option open to solo GPs; it's also possible to build a successful career investing purely on a deal-by-deal (DBD) basis.

In DBD investing, a “lead” investor (eg. an emerging fund manager) builds a founder relationship and presents the opportunity to invest in a company to their network of LPs. Each LP then decides themselves whether they want to invest in the company, on the basis of their own due diligence. An SPV (special purpose vehicle) is used to pool the investors’ money and take care of legal arrangements like governance of the investment, deal fees and carried interest. It’s a bit like a fund set up for one investment.

Last year at Odin we helped over 3,000 investors (primarily angels, high net worths and family offices) deploy capital into 420 SPVs led by emerging managers, backing both later-stage companies like SpaceX, Groq, OpenAI and Anduril, and very early-stage startups in incredibly exciting sectors like AI chips (Vaire), clean energy (Rivan), biological computing (Apoha) and much more. Often these investments are alongside the “tier 1” US firms named above.

Many of the best paid and best performing solo GPs on our platform invest exclusively this way, rather than raising funds — and their approach is, in my opinion, smarter and more flexible:

- They build a large portfolio at pre-seed, seed and Series A. They charge deal carry to investors, with no or minimal cash fees.

- To pay the bills they work a job that gives them excellent deal access and network anyway (the two key things VCs claim as their USPs). For example, they might have an operator role at a Series A plus company that's performing well, or do corporate finance work (fundraising for other funds, capital intros to their portfolio breakouts and other later-stage businesses via their network of Series B plus investors, family offices, etc.).

The benefits of deal-by-deal investing

Sticking to investing DBD has a host of advantages:

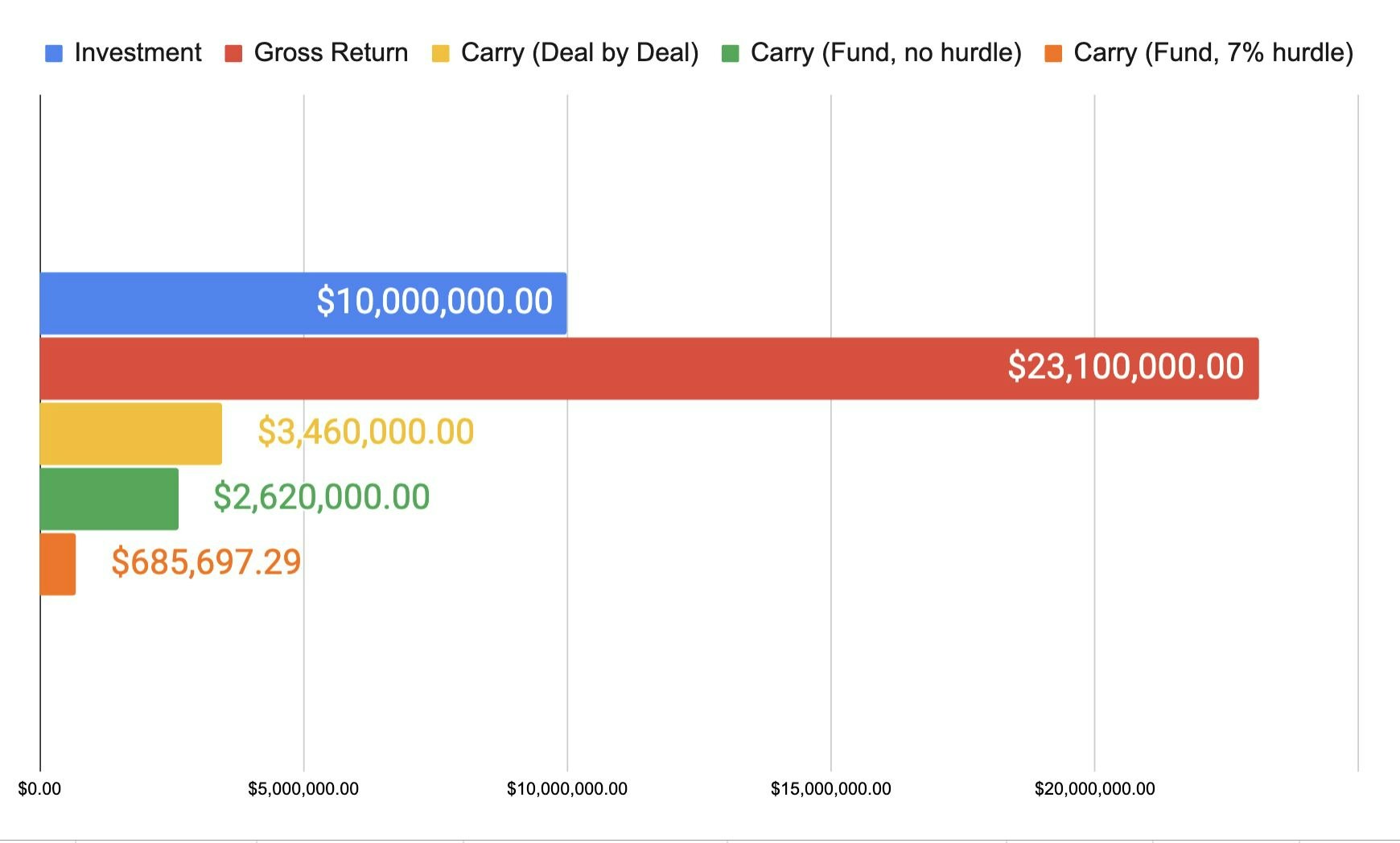

- You can charge deal carry on investments, rather than fund carry. If you’re confident you’ll perform, your unit economics on exits actually look much, much better — we're talking up to 5x more cash out in exit events on a typical 20 deal VC portfolio (see data from a sample portfolio below on this). Despite this structural disadvantage from their perspective, LPs are often happier with this arrangement, since they don’t typically pay management fees on SPVs. Remember, most VC firms lose money. LPs are often stuck paying the salaries of poor performing managers in their portfolio for 10+ years.

- You can write more flexible cheque sizes, and get access to better deals. If you’re not after a specific ownership percentage and not seen as a competitor to other funds, it’s easier to squeeze onto the cap table in competitive deals. We structured an SPV for Clay VC as part of their investment in the ElevenLabs pre-seed that was only £70k. It has already delivered over £4m in cash, and the SPV still holds 30% of their original equity in the company (which has tripled in value again since the initial liquidity event).

- You can invest outside of a strict fund mandate. This can be very impactful in a dynamic, rapidly changing market. Imagine you raised a fund to invest in crypto/Web3 in 2021. It’s hard to pivot. Change is only going to happen faster in the coming years. DBD keeps you nimble and able to take advantage of opportunities as they arise.

Deal by deal carry economics on an average fund can actually look much better. A “hurdle” is not common in DBD structures, but you do see it in funds — eg. the fund has to deliver a 7% annual return before any carry is paid on profits.

Even if you do later hope to raise a fund, DBD helps you to fine tune your fundraising skills (remember raising money is basically sales), build LP trust, grow your co-investor network and build out your track record on a part-time basis. This makes raising a fund in the future much, much easier.

We saw some incredible exits last year, the best delivering 70x cash on cash returns in 18 months (that ElevenLabs deal led by Clay) and 10x in 6 months (Praktika AI, led by Namat Bahram).. Both emerging managers who led these DBD investments are now well subscribed for their first funds.

The downsides of deal-by-deal investing

There are, of course, disadvantages to this approach:

- The best investments often look like bad investments initially, so they’re hard to raise money for DBD. Excellent performance in venture is about being non-consensus and right. For GPs, it’s hard to raise money DBD for non-consensus investments (that undersubscribed ElevenLabs pre-seed SPV is a good example).

- It can be slow. At the worst of times, raising DBD is like herding cats — chasing people urgently for wire transfers to help the founder get the round closed on time. This can also make it trickier getting into competitive rounds, since you can’t deploy as quickly as funds.

- It can be more faff (and $) for LPs. For LPs, DBD means more admin (more wire transfers, signatures, etc.) and potentially higher fees overall (due to deal carry — see this article for a detailed explanation of the economics of DBD vs fund carry). If they really back you, LPs are better off giving you committed capital and paying management fees, but benefitting from fund-level carry, which drives better alignment of long-term interests.

- It’s can be attractive to founders. For startups, a commitment from a fund is much more of a certainty than a commitment from a syndicate (which might fail to raise as much capital as they had hoped). This can make funds more attractive as investors.

However, beyond the pros and cons above, I simply don’t think running a VC firm is for most people.

Not only is raising money incredibly tough, each fund is a 10+ year commitment, and comes with significant fiduciary responsibility. On Fund 1, it usually isn't glamorous, and it certainly doesn't pay well.

Doing another job is often more fun and a better financial decision.

Deal by deal is the right way to test the water. And it may well pay better long-term too.