We all know that Europe has difficulty commercialising the innovation that takes place in its universities.

That’s true across the region. Spinouts represent only 0.03% of the UK’s overall company population, according to Beauhurst. And in Germany, spinouts per 10k inhabitants have decreased from 6.3 to 3.95 in the last 20 years, according to EFI.

But improving spinout numbers alone will not close Europe’s innovation gap. Looking to the US, where patent transfers have been constantly increasing over the last 20 years, Europe needs to look at technology transfer more broadly.

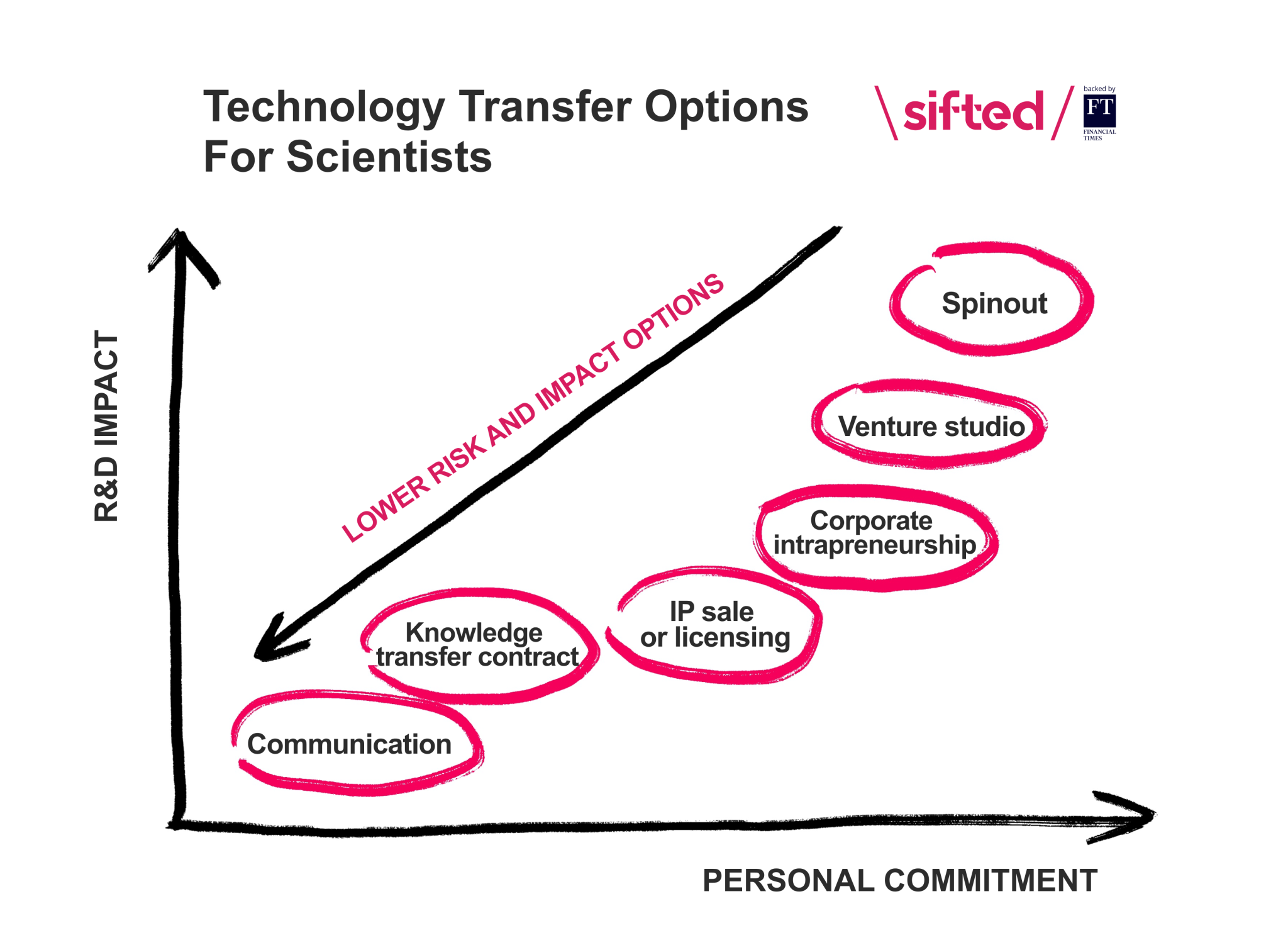

On top of that, not all scientists with relevant knowledge or intellectual property (IP) are ready to become entrepreneurs. Universities — and the tech industry — need to help scientific talent better understand that founding a spinout isn’t the only way to translate their knowledge and lab discoveries into commercial value. Here are a few other opportunities for scientists and academics.

Join a venture studio or accelerator

A venture studio is an organisation that focuses on creating and growing new startups. They work on only a few projects a year and help potential founders start a company from scratch, unlike accelerators or venture capital firms that work with existing companies. They actively support founders in the incubation process of a startup.

There are many venture studios — including Barcelona’s The Collider, London’s Deep Science Ventures, Merantix in Berlin and idealab in the US — that actively recruit scientists looking to either develop a new venture idea or join an existing team as a scientific cofounder.

Potential scientist-founders must understand, however, that signing up for such a programme requires a significant personal commitment to a full-time position, either by becoming an entrepreneur-in-residence at the studio or in a role at the newly incorporated venture. They will (most likely) receive fewer shares in any company they found than if they were to start the company independently. There will be more stakeholders to manage, too.

The payoff is high personal impact, a steep learning curve and at least partial participation in the future (financial) success of the startup while skipping the very difficult and lonely phase of starting a company solo. Unlike a spinout, founders in this situation are supported by a team that has helped build many companies from scratch before. They have the resources to supplement a founder’s weak spots, and most studios also provide the initial seed funding to develop the first product.

Join a corporate intrapreneurship programme

Another option for potential scientist-founders is to take a full-time position in an established company as part of a corporate intrapreneurship programme and develop their IP.

This option is best if the corporate can provide specific expertise and know-how, access to early adopting customers or direct market access.

Even if the idea is not a success, the founder is assured a full-time position at the company, with multiple career options

A founder’s commitment in this scenario is still high, as it requires starting a full-time position. There isn't the same risk as founding a company at a venture studio, however. Even if the idea isn't a success, the founder is assured a full-time position at the company, with multiple career options.

Yet this cosy fall-back option also illustrates the downside of joining an established company. Intrapreneurs may have to deal with changes in internal priorities; the corporate could even decide it wants to give up on an idea. That’s why incubating an idea that has high strategic relevance to the company is so important.

For global laser and manufacturing giant Trumpf, for example, metal 3D printing as an affordable and simple way for product development is of high strategic importance. So when the One Click Metal team pitched their idea in their intrapreneurship programme in 2019, Trumpf invested to spin it out as an independent company.

Sell or out-license your IP

Companies are continuously searching for new technologies that they can use to build innovative products. Take sustainability for example — as more customers demand planet-friendly products, corporate R&D and innovation projects are increasingly searching for external collaborators.

They often do this by buying or licensing IP, providing academics with a speedy way to market for their technology or inventions without having to join a new company.

Depending on the terms, royalty fees can either be a one-time payment or regular payments based on a measure of IP usage. Ideally, the technology transfer office (TTO) at the academic’s institution will also support the negotiation. And while the terms should feel fair to the inventor, the focus should be on enabling the industry partner to commercialise the IP, which will eventually benefit both parties. Inventors and academics can reinvest the fees to advance their research. These kinds of deals can even lead to more collaboration down the road.

Knowledge transfer contracts

For academics that don’t yet have transferable IP, such as a patent, a knowledge transfer contract with an industry partner is also an option. This scenario is attractive for both sides if the academic’s expertise is relevant to a specific R&D challenge the company is currently facing.

In this scenario, the academic’s commitment is low. All they have to do is share what they already know. The downside, however, is they cannot influence what happens with this knowledge beyond the transfer.

Share research through writing

Corporates, investors, talent or potential customers won’t want to work with academics if they don’t understand the value of scientific research. That’s why communication is so key in technology transfer — and usually a prerequisite for all the scenarios above.

Good communication provides direct feedback and simultaneously can help academics build a valuable network

Academics need to make it a habit to write about their research in blogs or social media for relevant, but non-specialist audiences, in non-scientific language. Or they can attend relevant conferences or workshops in an industry where you think your research might be practically applicable. Understanding the motivations, interests and goals of audiences with different backgrounds is key to getting buy-in down the road.

Good communication provides direct feedback and simultaneously can help academics build a valuable network. It can be a route to taking on expert advisory roles in companies or investment committees via which, again, scientists can bring their expertise to bear without having to start their own companies.

Conclusion

As we have shown, there are multiple ways for scientists to leverage their expertise and help improve technology transfer. The right choice of how much to get involved depends on the area of research, the maturity of the IP, and last but not least, personal preferences. But any action is one step towards closing Europe’s innovation gap.