A few weeks ago delivery company Just Eat announced plans to move away from using 'gig economy' workers in the UK, instead offering driver benefits including hourly wages, sick pay and pension contributions.

The company, which merged last year with Netherlands-based rival Takeaway.com, in effect threw down the gauntlet to rivals such as Uber, Deliveroo and Glovo who are still using workers with no employment rights and benefits.

But Just Eat's announcement is merely the latest development in a shift across Europe — encouraged by growing regulation and also a growing discourse against gig workers — that has seen others like courier federation CoopCycle look for a new employment model.

Meanwhile, Uber is awaiting a verdict from the UK Supreme Court, which could force it to pay drivers an hourly minimum wage and holiday pay.

These shifts could see Europe at the vanguard of a global movement away from using gig working — that is, if other European tech companies follow their lead.

“The right thing to do”

Just Eat’s UK managing director Andrew Kenny tells Sifted that the decision on a new employment contract comes from a place of moral responsibility.

“We feel very strongly as a business that affording couriers the protections that come with this model is the right thing to do. We're fortunate that as a successful and profitable and market leading business that we're in a position to do so,” he says.

While declining to put a figure on it, Just Eat told Sifted that the costs of this new model are “significant”, as the company will be supplying riders with e-scooters and bikes, which will be collected from a central hub.

“It's a very different model, we have a hub in central London where the electric bikes and electric scooters are stored, where couriers can come in and take a break, use the facilities and have a hot drink, so you're dealing with real estate in London and as we expand, elsewhere,” explains Kenny.

While this might present a significant cost for Just Eat, Kenny believes it also goes some way to reducing the stress of vehicle maintenance costs that gig economy workers face.

“We're providing them with the electric bike or electric scooter, so the maintenance is all taken care of for them. If they have an issue they jump on another bike so they don't have the same stresses that go with alternative models where you would be responsible naturally for that kind of thing yourself,” he says.

It is worth noting that Just Eat has long differed from competitors like Deliveroo and Uber Eats, in that it also relies on delivery drivers employed by the restaurants themselves. This means that the cost of giving its own couriers employment contracts is relatively cheaper than it would be for rivals, as they represent a smaller portion of the delivery fleet.

Ownership

Another example of a growing response to delivery apps is the rise in rider-owned cooperatives.

Based in Paris, CoopCycle is a federation of courier platform cooperatives that are active in more than 50 cities in eight countries.

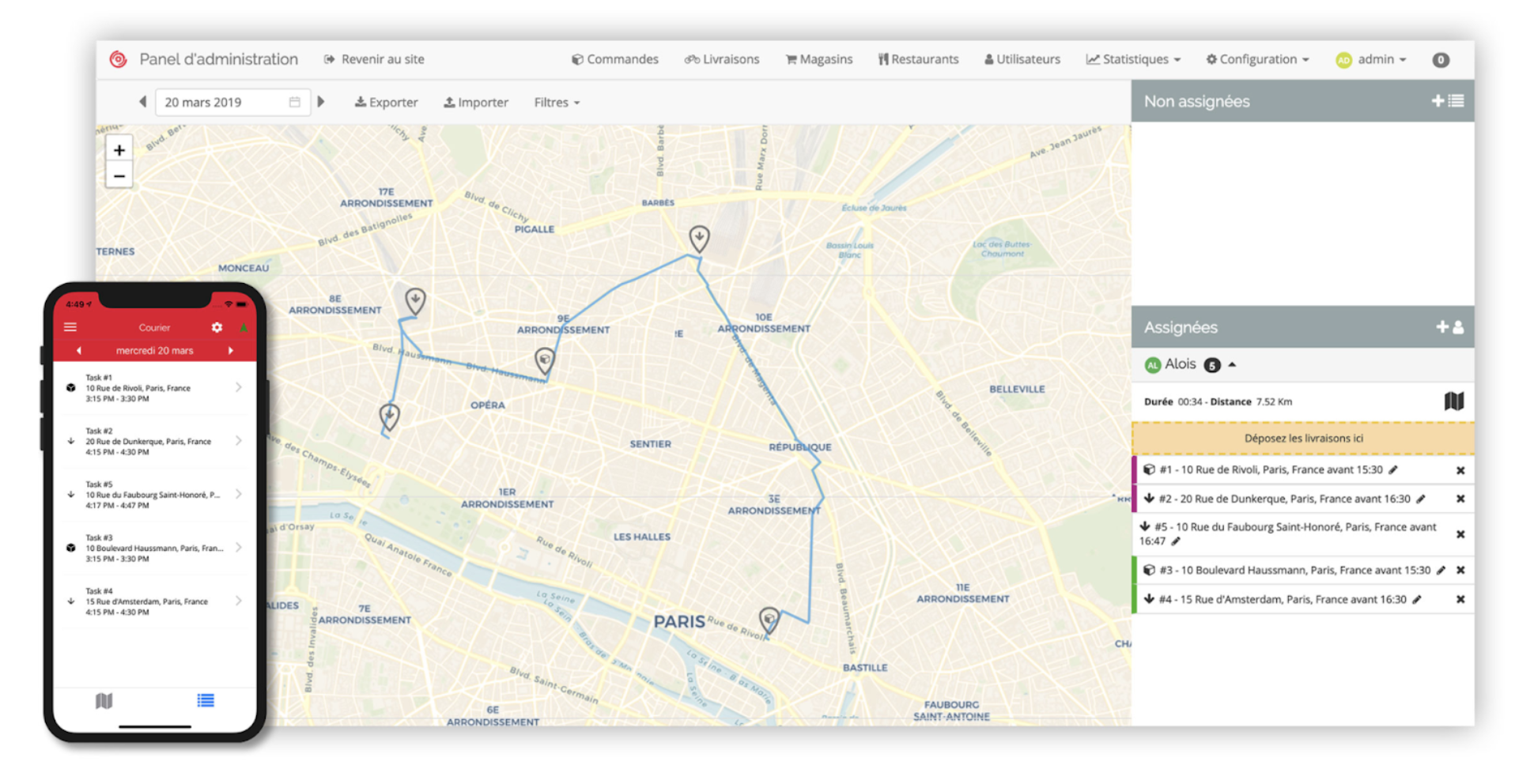

CoopCycle helps couriers launch their own cooperative delivery businesses, sharing the tech for the platform software, the customer facing smartphone app, and knowledge around business strategy and pricing.

All riders working with the CoopCycle model are employees and, beyond giving couriers stable income, organisers say this also makes the work safer than a pay-per-job model.

“Being a courier is a dangerous job, you have to cycle as fast as you can to complete as many jobs as possible,” says Adrien Claude, European coordinator for CoopCycle. “We are not in a model in which the faster you ride and the more lights you jump, the more money you get.”

Restaurants are sick of the service because, as couriers aren't treated well, the consequence is that the service is shit.

Claude adds that the employee model leads to a better relationship with restaurants: “Restaurants are sick of the (gig economy) platforms. They're sick of the service because, as couriers aren't treated well, the consequence is that the service is shit.”

CoopCycle relies on exclusive deals with restaurants to make the service viable in the face of the big, heavily-backed alternatives with big marketing budgets.

“We can't afford sponsorship with a football club, we can't afford advertising on TV,” Claude explains. “What we have to sell is something different. We want a virtuous circle between customer, city, restaurant and couriers, with couriers protected.”

The scale of CoopCycle’s operations is understandably much smaller than gig economy models. Claude says that in the federation’s most active cities (Nantes, Berlin, and Grenobles), cooperatives employ between 10-20 couriers.

And while growth-minded observers might sniff at such numbers, the cooperative movement is gaining momentum, with accelerators and incubators popping up on both sides of the Atlantic.

A third way?

Those who stand accused of exploiting drivers and riders see it differently.

Uber chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi has previously argued for what he calls a “third way”, where drivers keep the flexibility of the self employed model, while still receiving some benefits like holiday pay or sick leave.

This, according to some campaigners, is disingenuous.

James Farrar is a former Uber driver and general secretary of the UK-based App Drivers and Couriers Union. He says that this “third way” already exists in the UK, but is exactly what Uber are arguing against in the courts.

“If you look at what he's arguing in the US, he's arguing for something between self employed and employed. We have that here in the UK and they've spent the last five years fighting against it, telling everybody the law was obsolete and needed to be updated and of course this couldn't work,” he says.

The tech platform is currently fighting a decision made by a UK employment tribunal that classed Uber drivers as "limb (b)" workers.

Limb (b) is a legal worker classification in the UK for so-called “dependant contractors”, who are self employed but “provide a service as part of someone else’s business.”

This, says Farrar, fits the Uber model perfectly, and would entitle drivers to just the kind of benefits that Khosrowshahi claims to support. Uber is currently contesting the classification in the UK Supreme Court.

“It's a prime example of Uber saying one thing in California and then spending millions on lawyers on this side of the Atlantic to defeat the same argument,” Farrar adds.

Uber’s reluctance to recognise its drivers’ status as limb (b) workers in the UK exposes the hypocrisy of the well-worn argument that “regulations are too out of date” for tech platforms.

And as pressure mounts on gig economy platforms from courts, competitors and customers alike, big question marks still hang around whether their “growth at all costs” model can be sustainable, and if Europe can come up with a different model.