Think you’ve got it tough fundraising? Try doing it when English is your fourth language, you’ve only just arrived in Europe, you don’t know anyone and Trump's travel ban means you can't set foot in the US. That's the reality for many refugee entrepreneurs who are trying to build startups in the face of even greater odds than their local rivals.

Applications for asylum in Europe have been on the rise since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August last year, and the war in Ukraine has created yet another crisis of displaced people. Given the chance, migrants and refugees are often keen business builders — in the UK alone, there are more than 450k people from 155 countries who have founded companies since moving to the country, according to the Centre for Entrepreneurs.

So what is life like for refugees who want to join Europe’s entrepreneurial community?

Exclusionary ecosystems

“You need to find a cofounder who is a white male,” says Yama Saraj, founder of Paris-based sports hardware startup SensAI. Saraj has been living in France since 2019 and in Europe since 1988, when he was 11 and his family fled Afghanistan and settled in the Netherlands.

“If I had the opportunity to relive my life, I would definitely try to find a good Dutch or French cofounder who could be the face of the company. There are so many institutional and cognitive biases people have, which are so tiring to fight against.”

SensAI recently raised €20k in angel investment, won €42k from La French Tech’s “Tremplin” programme and is now being incubated by École Polytechnique, but Saraj says he’s still facing discrimination in funding.

“I realised how hard it is for any startup to get funding, but specifically how disproportionately hard it is for immigrants, people of colour, to get access to resources,” he says. “I’m trying to get support and people really question like, ‘Wow, is this really your idea?’ Or like, ‘Wow, you speak such good Dutch.’ After 20, 30 times of hearing that you realise that’s not actually a compliment, these guys have fucking low expectations.”

With SensAI, Saraj is trying to build a business that will improve its users’ health and wellbeing, but his professional motivations go beyond just wanting to make a great product.

“I’ve tried to make something out of life to bring a level of dignity and honour to my family. And also to disprove a lot of people, [to show] that we immigrants, we're not useless people, we can be very productive citizens and participate and contribute to our society,” he says.

Lack of access to funding

Nour Mouakke, founder of meetings and events booking platform Wizme, agrees that access to funding is a big issue for refugee founders: “There is no support on that angle.”

He moved from Syria to London in 2009 to complete a master's degree in marketing at Durham Business School, before landing a job in business development at InterContinental Hotels Group in the UK. But after the war broke out in Syria in 2011, he applied for refugee status in 2014 as a safety net as he was sponsored by his employer. “Also, I wanted to start up my business so badly. Unfortunately, when you are sponsored, you're tied up to the company where you work so you can't really start a business.”

And even with more than a decade of experience in events and hospitality under his belt, Mouakke points out that professional networking is a big challenge when you arrive in a new country.

“The other big issue is the network. I moved from a country where I had a network and I knew people to help me get things done. All of a sudden you’re just thrown into a new world where you need to find your way and find the right people to get in touch with,” he says.

“Tight-knit networks are good for trust, and people can innovate faster. But sometimes it can also feel, for people from minorities groups who’ve just arrived, a little bit harder to get in there. These are implicit exclusion mechanisms,” adds Saraj, who is trying to help other refugees get into work in Europe.

“Two million people fled Afghanistan. These are people who are students, professors, doctors, engineers. These people had to flee their country. The shame and the humiliation — it is such a dehumanising process. I'm trying to get them out of this asylum system as soon as possible so that they can interact with society.”

More initiatives to support refugee entrepreneurs are beginning to appear. The Human Safety Net recently launched a refugee-focused incubator in Paris, while Vifre offers online resources for budding entrepreneurs who are settling in new countries. There’s also Incubators for Immigrants in the Netherlands and the SINGA Business Lab in Berlin.

A different level of pressure

It’s not only institutional bias that these founders face. Rami Kalai is cofounder of inbox management platform Compose, headquartered in London. Originally from Syria, he describes how his nationality has created complications that other entrepreneurs would never get close to experiencing.

“Things got trickier when we were raising our seed round because we really wanted to raise from US VCs and being Syrian means you can't get into the country because we're on the travel ban,” he says.

Kalai was later able to find willing investors in the UK, and is clearly grateful to be in a place where he can safely build a business.

“There are no MiGs [fighter jets] flying overhead. I've had MiGs flying overhead, I've seen them shooting rockets down the road. That doesn't happen here. So I think being grateful and being able to really make use of what you do have is important,” he says.

But while he’s grateful to be safe, Kalai also describes how the normal pressures of starting a business can be compounded for refugees.

He recalls the conversation he had with his father, after his family spent their savings on sending him to Imperial College London to study electrical engineering: “My parents sold our home in Damascus for a fraction of what they bought it for, with the intention of sending me to Europe to study. My dad had one of those conversations with me that you don’t forget. He told me: ‘This is the money we have. We’re going to invest it in your future because everything we've built over decades is lost because of the war. So hopefully, you can build something somewhere else.’”

But the tone of these conversations changed after Kalai turned down a job at JPMorgan to build his startup.

“I got a return offer from JPMorgan — this was before we had any funding for the startup — and I didn't want to take it,” he remembers. “My dad was freaking out, because all he wanted was something stable. He was like, ‘This is a stable job. We have no money. You should take this.’ And we had a huge argument for a few days. When we raised the pre-seed round then he was like, ‘Well, yeah, actually, maybe you can do this.’”

Potential

Wizme’s Nour Mouakke describes a similar experience of family pressure as he grows his business.

“I’ve given up on the things that any startup founder would do. The job, the salary, put all my savings in, sweat, equity, skin in the game. I've done that but the difference here is, I put my skin in the game, but I have family and friends in Syria, who need my support and I’ve given up on my salary to be able to support them. I have four younger siblings. This makes things way harder,” he says.

But Kalai adds that, while investors and entrepreneurs need to be mindful of the challenges that immigrant and refugee founders face, they should also be aware of their potential.

“When I meet a founder who’s a refugee or an asylum seeker or an immigrant, I think there's this chip on their shoulder, because I experienced it. And I imagine that they have some similar motivation, which means they'll probably outwork their competitor,” he says. “There’s some element there that's going to drive them that little bit more, and it's going to make them push themselves that little bit more. I think if we can actually build a constructed environment to facilitate that, then great things could happen.”

More than anything else though, these founders hope that — rather than their personal stories or the journeys they’ve been forced to make — it’s the products that they’re building that will do the talking.

Refugee startup stories

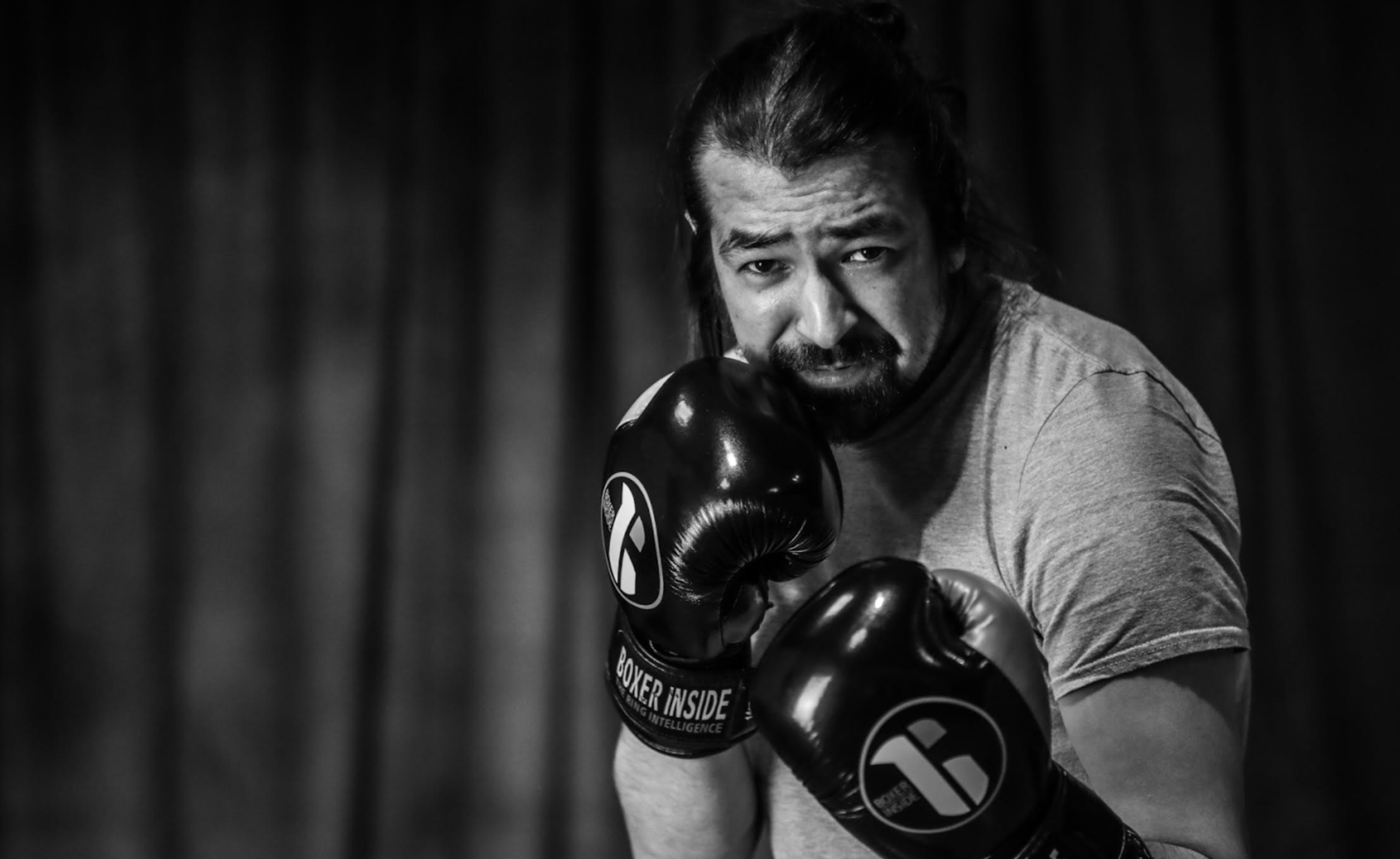

SensAI — founded 2019

The pitch: SensAI is developing camera and motion sensor systems to convert recycled car tyres into smart punching bags. The tech is combined with digital training programmes that are designed to improve physical and mental health for users. Founder Yama Saraj hopes that using recycled materials will make the martial arts-informed technology accessible to people in developing economies, aiming to create “the Peloton of boxing”.

Wizme — founded 2015

The pitch: Booking a complex event with large groups, multiple meeting rooms, tech needs and catering options? Wizme is a smart booking platform that allows groups and event planners to easily book everything they need for an event, while also giving venues the tools they need to streamline their event hosting. Founder Nour Mouakke spent more than a decade working in events and hospitality, where he witnessed big inefficiencies in events management.

Compose — founded 2019

The pitch: Compose is an inbox management tool that brings your work apps together to make collaboration and conversation effortless. The product creates a single inbox from tools like email, Slack, Notion and Google Docs in a productivity app that promises to help you view, organise, action and find your most important conversations across all your workflow.