In the increasingly competitive world of quantum computing, Paris-based startup Pasqal is starting to make a name for itself.

Governments are showing a strategic interest in its potentially revolutionary technology: it’s so far raised $140m from investors including the European Innovation Council, Singaporean sovereign wealth fund Temasek, France’s state bank Bpifrance and its Ministry of Defence.

The startup, which was founded by physics Nobel Prize winner Alain Aspect and is named after the 17th-century inventor of the world’s first mechanical calculator Blaise Pascal, is present in eight countries. It has also secured partnerships with big industry players ranging from energy company EDF to oil and gas giant Aramco.

“It’s a marathon that will be hard to win, but for now we are among the frontrunners,” says Nicolas Proust, Pasqal’s head of strategy and corporate development.

But is that true?

Scientists predict that quantum computers will unlock unprecedented computational power. In the race toward this goal, Pasqal is up against US behemoths with substantial financial resources, like IBM and Google, as well as numerous other better-funded startups.

It’s a challenge far from being accomplished — but the startup is not discouraged. “We have the right technological approach and a business strategy that works,” says Proust. “We are confident that we are doing everything we can to win.”

Qubit counts

For now, quantum computers can’t do much: high error rates and the limited size of quantum processors significantly limit their power.

Companies are dedicating much of their efforts to creating larger devices — which means increasing the number of “qubits” that a quantum processor can handle.

Qubits are tiny particles that carry quantum information. They are very unstable, meaning that manipulating them at scale is a huge scientific and engineering challenge.

Pasqal, which uses a particular type of qubits called neutral atoms, currently commercialises a quantum processor with about 100 qubits, and the company says that a 200-qubit device is “coming soon”.

These processors are still far from showing an advantage over conventional computers, with customers currently investing in the technology to prepare for when more powerful devices hit the market.

“Today, the added value of our product is to be at a level of performance, on certain applications, that is near that of the best conventional computing methods,” says Proust. “But it means customers can test applications and get a clear vision of what they’ll be able to do in the coming years.”

The French startup is partnering with pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson and French bank Crédit Agricole to explore how quantum computers could eventually serve use cases like drug discovery or portfolio optimisation.

Pasqal’s R&D roadmap — which focuses on technological developments rather than commercial products — targets 1k qubits in the next 12 months and up to 10k qubits in 2026. At that point, says Proust, the startup expects to be able to demonstrate that its device has generated industrial usefulness in real-life business use cases.

The French startup is tailing IBM, one of the leading companies in the space, which is exploring another approach to quantum computing based on electrons, known as superconducting qubits.

The US tech giant, which has poured billions of dollars into its quantum computing research efforts, currently commercialises a 127-qubit processor. Last December, it unveiled its 1,121-qubit prototype processor, named Condor, at the IBM Quantum Summit 2023.

Neutral atoms

Pasqal’s approach to building quantum computers, which is based on neutral atoms, is one of the reasons that experts are bullish about the company’s ability to compete — even against IBM.

“IBM is definitely one of the frontrunners in the quantum race,” says Dominik Slonecki, deeptech investor at US VC Presidio Ventures. “Still, scaling up superconducting qubits-based processors, the technology IBM is betting on, is an immense challenge.”

“It's not unlikely that the ultimate winners of the quantum race will rely on an alternative technology.”

Neutral atoms are emerging as good candidates, with recent studies demonstrating that the technology lends itself particularly well to scaling. Other approaches exist too, such as photonic qubits, trapped ion qubits and silicon spin qubits, all with their strengths and challenges.

Pasqal is not the only company to be working with neutral atoms. In the US, California-based Atom Computing produces 100-qubit processors and is developing a device with over 1k qubits. Boston-based QuEra, meanwhile, already offers a 256-qubit quantum processor and is targeting 10k qubits in 2026.

More recently, Germany’s planqc joined the ranks of neutral atoms-based quantum computing companies. The startup is still working on a 100-qubit prototype.

Business first

But it’s not all about qubit counts, says Proust.

“We can demonstrate a certain number of qubits but the real question is: what can we do with them?” says Proust. “This is where we differentiate ourselves.”

Although it was founded by academics, Proust says that Pasqal’s focus is not only on scientific research, but also on how to commercialise its technology.

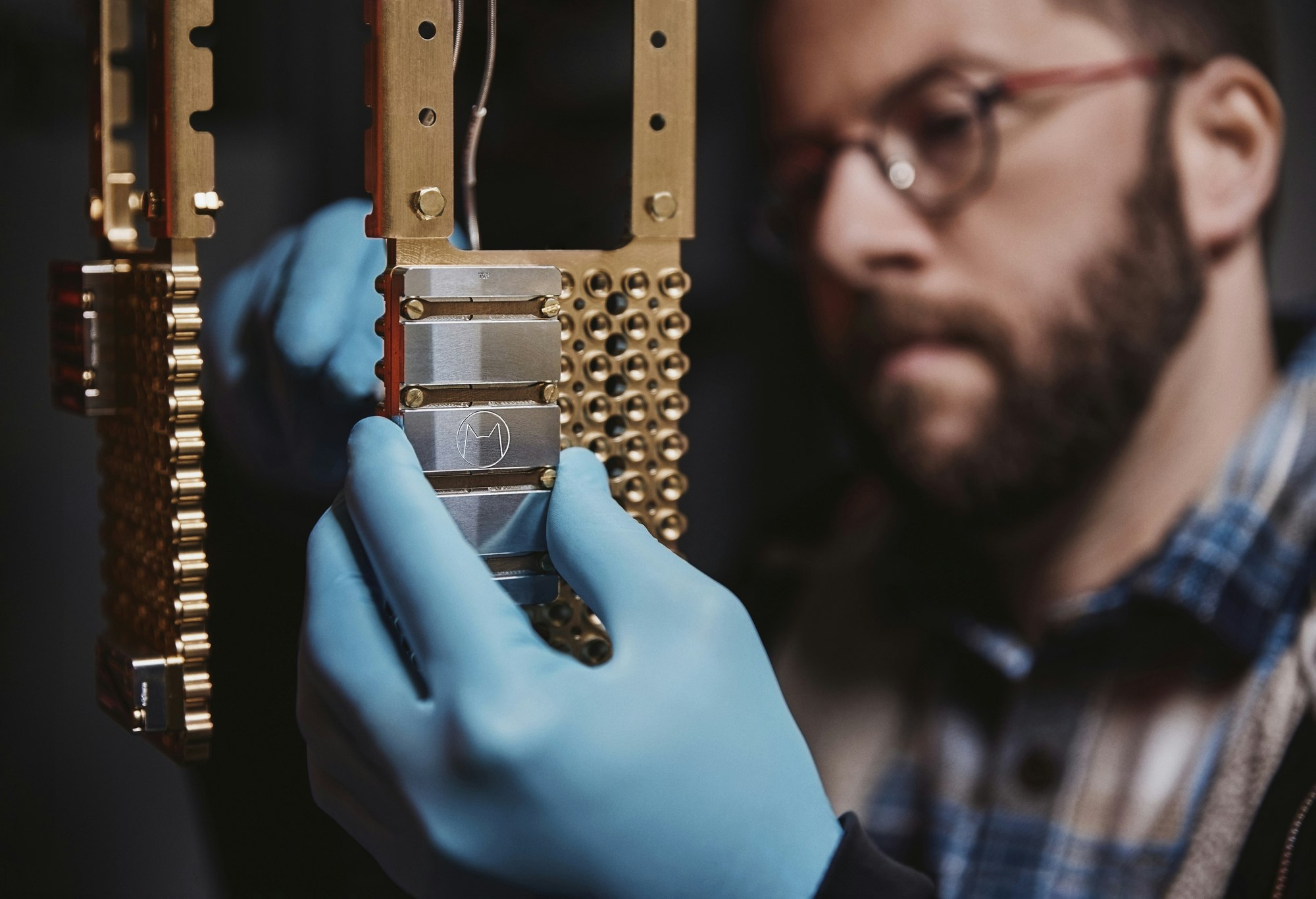

The startup is one of the few companies around the world building and selling quantum processors to customers — for now, mostly governments.

Pasqal produces quantum processors in its sole factory in France. To date, only two have been publicly announced, which have been sold to EU-backed high-performance computing centres in France and Germany and will be deployed this year. Declining to confirm a specific number, Proust says that Pasqal has produced at least one other processor and, in total, less than 10 devices.

That may seem like few, but Pasqal’s production of quantum processors is similar to that of its competitors. Companies that build and sell quantum processors — such as French startup Quandela, the UK’s Quantinuum, Finland’s IQM or US-based Atom Computing — have yielded little more than a single-digit number of units. IBM, for its part, leads the market with dozens of devices produced to date.

“Today, hardware is the rarest resource,” says Proust. “Right now, the production of quantum processors globally cannot match demand.”

To meet this rising demand, Pasqal is opening a second factory in Canada this year and is planning to inaugurate a third facility in South Korea by 2025.

Demand is largely coming from governments for now, says Proust, but he expects to see orders arrive from private companies too: “We hope to have some good news before next summer.”

Scaling up

Last year, as part of its international expansion strategy, Pasqal appointed Wasiq Bokhari as the company’s new US-based chairman — a serial entrepreneur turned director of strategic initiatives at Amazon, who initiated and led the tech giant’s quantum computing efforts.

His role is to take the company from early-stage to scaleup as it increases its production capabilities.

“There are two things to think about,” says Bokhari. “First, how to scaleup whichever is the most stable version of the quantum processor in terms of number of units. And second, how to realise higher and more interesting specs for new machines, and then repeat the process of scalability for these.”

“That’s an operational scaleup problem. It shows we are going from technology to a business.”

Pasqal doesn’t disclose how many quantum processors it aims to eventually produce, but Bokhari says the objective is a “significant multiple” of current numbers.

These are metrics that investors are watching. Quantum computers sell for tens of millions of dollars, according to Christophe Jurczak, managing partner at quantum-focused VC Quantonation, who has invested in Pasqal — meaning that companies that manufacture the devices are already earning solid revenue.

“What’s changed in the past few years [in the quantum computing sector] is that we want our startups to think in terms of commercialisation, not only technological development,” says Jurczak.

“Growth investors are looking for commercial validation, so it is necessary to go towards that. Pasqal has had this mindset from the start.”

Funding growth

Convincing growth investors, it turns out, is one of Pasqal’s top priorities at the moment. The startup raised a €100m Series B last year — but in the capital-intensive world of quantum computing, the next round of funding is never far off.

“With €100m, we can go far enough that we are not worried,” says Proust. “But what’s certain is that we are constantly fundraising. I can’t say the next round is far away.”

And in Europe, where Proust describes post-Series A funding as “failing”, finding the big VC tickets that the company needs isn’t easy.

In the US, some of Pasqal’s competitors have raised comparatively colossal amounts: PsiQuantum, for instance, has bagged just under $1bn to date.

“Pasqal will need to raise again, and clearly in the triple digits,” says Jurczak. “But they are capable of finding international investments, not only European.”

The French startup is already backed by Singaporean VC Temasek and Saudi Arabian oil and gas giant Aramco. It has a presence, through subsidiaries and partnerships, in eight countries — namely France, the Netherlands, Germany, the UK, Canada, the US, South Korea and Saudi Arabia — and plans to double down on the US and Asia.

In a sector that is seeing more consolidation, there is also another option: to be acquired by a wealthy competitor.

“Having a technology that equals or surpasses that of large international actors is attractive,” says Proust, declining to confirm whether the company has received any offer to date.

“We’re clearly seeing consolidation movements in our portfolio,” says Jurczak, “and some companies are thinking about it.”

“We are very interested in seeing this type of operation. It’s normal — it shows the sector is maturing.”