The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Art of Disruption

Sebastian Mallaby

Allen Lane; out now

So let me get this out of the way: Sebastian Mallaby’s new book is something that I (and hence, you all) have been waiting for. It is the book about VC that desperately needed to exist, the first in-depth account about the industry not written by a VC or an economist. Based on more than 300 interviews with a set of big-name insiders, it's the latest attempt to explain the importance of VC in creating our (digital) economy.

While we’ve learnt a lot about the biggest startup successes of our time from accounts like Super Pumped on Uber, Bad Blood on Theranos or most recently The Cult of We on WeWork, this is the first time an author has focused on the perspective of the investors, rather than the "wunderkind" entrepreneurs. I’ve been frustrated about the lack of focus on those I call the kingmakers, the people who actually decide who gets a shot at building the next herd of unicorns.

Mallaby provides us with intimate glimpses into the lives of some of the grandees of VC: Sequoia’s Mike Moritz and Roelof Botha feature together with Kleiner Perkins’s John Doerr and the Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) founders, among others. Given the intimate insights Mallaby unearths, along with his perfectly executed narrative, The Power Law should be on every tech founder’s — and self-reflective VC’s — reading list.

The Power Law should be on every tech founder’s — and self-reflective VC’s— reading list

But I want to focus on one fundamental question I have about Mallaby’s account, particularly given Sifted’s mission to illuminate what is happening in European tech: why is there not a single page about Europe in the 400-page book?

Yes, VC started in the US, on the East Coast (as I will remind everyone despite the West Coast ecosystem’s dominance in the public imagination). Yes, the most well-known VCs and VC-backed companies are still there.

But Europe plays a massive role in the tech ecosystem, including in venture capital, and has since before 2019 when Mallaby’s account stops. In fact, according to the recent State of European Tech report and Crunchbase data, European VC was almost on par with American financing last year (in terms of seed funding, for instance).

I can’t add the missing chapter to the book, but I’ll propose some comparative observations complementing Mallaby’s main findings, extending a work almost exclusively focused on US VC and its expansion into China and India.

The power law — also in Europe?

The thread which weaves the book together and gives it its title is the concept of the power law. Simply speaking, a VC invests expecting returns following a power law, rather than a normal distribution: a very small number of startup investments will be fund-returners and generate 100x the invested money while most of the others will lose or just about make back the investment.

My question is simple: does the power law assumption (and real distribution of returns) work the same way in European VC and does this strategy have the same domineering influence?

While data is overall not as reliable as in the US, on an individual fund level the reliance on unicorns in the EU has grown dramatically, too. Media, data providers and European policymakers alike are obsessed with creating unicorns — while on the flipside, a similar number of startups fail (around 90%) within seven years of inception as in the US. The dependence on the outsized returns of a small number of startups is a strong part of the narrative in Europe, too.

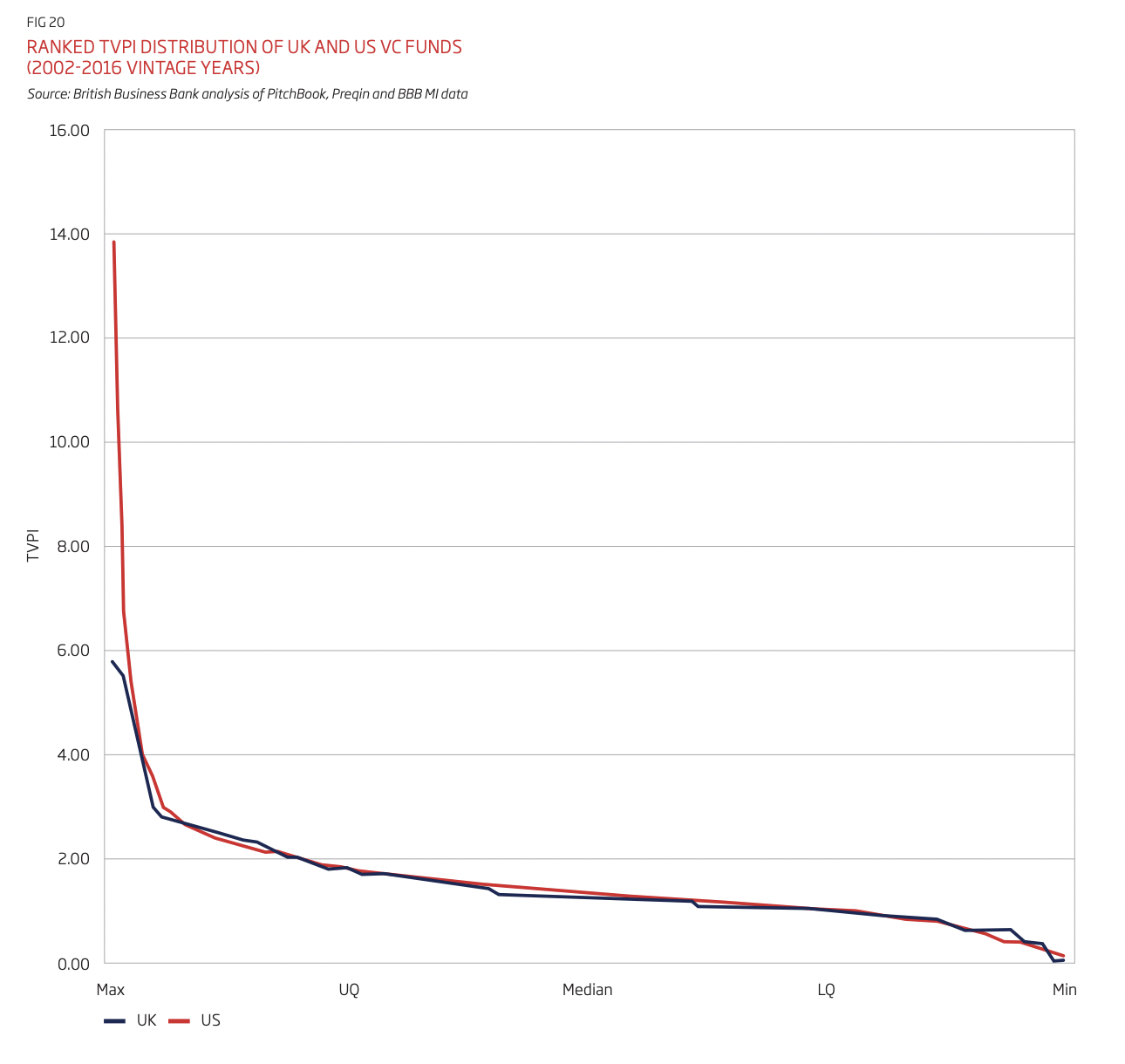

The power law is something that describes VC returns on an industry level, too. Only a small number of funds (5-10% depending on the year) significantly outperform a comparable basket of stocks. Does that also hold true for Europe?

VC returns in Europe have historically performed far worse than the US, but that has changed recently. Fund returns in Europe follow a similar biased distribution to the US, but with a major difference: ecosystems like the UK are lacking the mega-outliers on the fund level. What that means is simple: the top 10 funds in Europe are outperforming the average (and are the only ones really worth the risky investment), but they are far away from the extreme power law distribution — and hence the market power — of their US counterparts.

The consequences of this are significant. As many conversations with asset owners (LPs) over the last years on both sides of the pond have made clear to me, the top US funds dominate even their LPs. This power relationship is what allows a fund like Sequoia to drastically revamp its business model and take management fees from LPs for holding public assets.

This overarching influence of a very small number of funds is also prevented in Europe by the amount of government money in the market. Publicly funded LPs, like the European Investment Fund or KfW Capital in Germany, are incentivised by financial returns but industrial and scientific development as well.

All of this to say: the Europeans have, especially recently, been chasing unicorns and accepted common startup deaths almost to the same extent as the Americans, but they haven’t quite generated the same power law as their US equivalents, leaving influence and market dominance more distributed.

VCs and adding value

A second theme Mallaby returns to throughout the book is how involved VCs are in the startups they back. Arthur Rock, one of the earliest VCs, liberated the founders of Fairchild from their corporate claws; Sequoia got really hands-on with companies like Apple and provided true "value-add". Y Combinator and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund turned this principle upside down and focused on being founder-friendly and uninvolved. More recently, firms like a16z have whole armadas of support staff available to help build and scale the ventures they invest in.

How do European VCs map onto this spectrum?

I won’t be able to do the far-reaching ecosystem justice but want to offer some pointers for others to fill in. We’ve created strong incubation and acceleration processes in parallel to VC with players such as Entrepreneur First and Antler working in a very entrepreneur-friendly way.

Similarly, "value-add" VCs have developed more strongly in Europe; from heavyweights Atomico, HV Capital and Balderton to smaller, more specialised players such as Kindred and policy-focused Form. European VC is strong on supporting founders along their journey, both in the form of capital across stages (sister funds LocalGlobe and Latitude or Balderton’s recent addition of a growth fund are good examples) and direct support with hiring, marketing, ESG and fundraising. The ecosystem has definitely been further specialising and differentiating itself in contrast to its first decade of "opportunistic" and often copy-cat focused — remember the German entrepreneur Samwer brothers? — investing.

Room for more questioning?

What has for a long time been an observable difference is the lack of a strong cult of the individual in Europe. Similar to most of the startup-centred books which zoom in on prodigy founders, Mallaby also follows almost exclusively individual men who lead American VC funds. What is missing is a stronger focus on excavating principles, beyond the power law and level of VC involvement. Has the focus on the — often charismatic — VC personalities led him into being wooed by their own justifications, too?

In any case, Mallaby ends with a very strong defence of VC as an employment and innovation-generating engine of growth, albeit with a lack of diversity, which Mallaby is critical of throughout the volume.

What is missing is a stronger focus on excavating principles, beyond the power law and level of VC involvement. Has the focus on the — often charismatic — VC personalities led Mallaby into being wooed by their own justifications, too?

Given the hundreds of conversations I have had with VCs over the last four years, Mallaby’s conclusion leaves me with questions. Sure, talking about the lack of diversity is a good and safe start; but pushing away any concerns with VCs funding the wrong startups (the ones they can quickly blitzscale into unicorns à la Reid Hoffman) or funding simply the wrong things (not solving important issues, for instance around infrastructure, as Mark Andresseen himself recently lamented) seems like a missed opportunity.

Taking the ongoing tech-lash seriously and extending it to VC is something I was hoping Mallaby would do. A comparative view on Europe versus the US, where a drive towards ESG, impact or deeptech have so far been much less fruitful, could have been a good endpoint too.

The above critiques are perhaps more a function of my own expectations. I surely expected it to have a global view. But as for the quality of the book, I can only repeat what I started this review with: go and buy The Power Law.

It is a fantastic account of how American venture capital has developed and some of the most important rules that govern it. Let’s use Mallaby’s brilliantly executed observations of VC as an opening for a long-overdue, ongoing debate and continue our scrutiny of the kingmakers’ world. But I hope the next account includes Europe as well.

Dr Johannes Lenhard is a research associate and centre coordinator at the Max Planck Cambridge Centre for Ethics, Economy and Social Change. He is writing a book about the ethics of venture capital and is also the coauthor of Better Venture. He tweets at @JFLenhard.