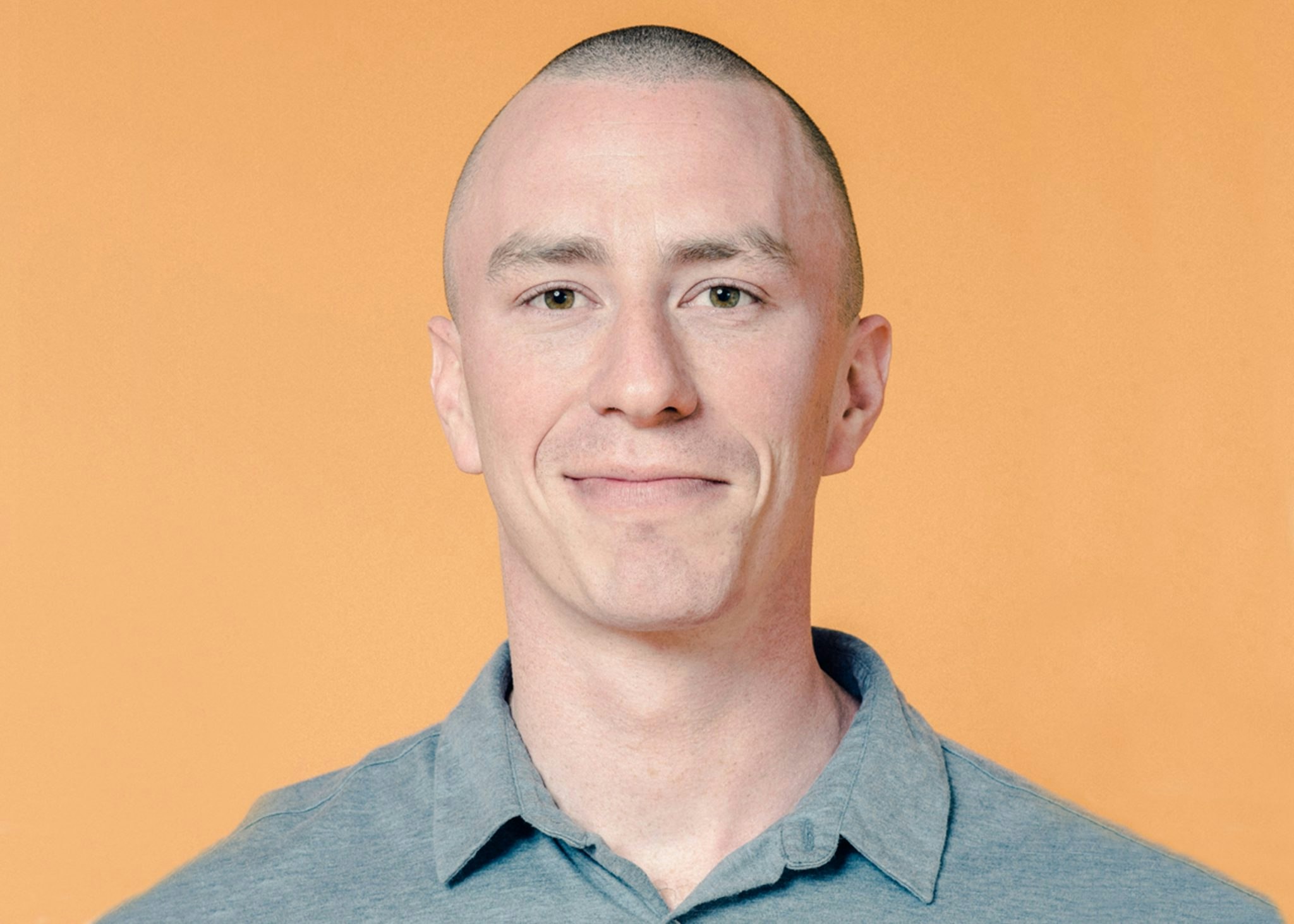

“If you don’t know what normal looks like you are going to get screwed,” says Dan Garrett, cofounder and chief executive of Farewill, the London-based will-writing startup, looking back on the experience of raising a £7.5m Series A funding round last January.

Negotiations for a startup’s first serious tranche of money can be full of pitfalls for an inexperienced founder team. The balance of power is vastly weighted towards the investors who have hundreds of deals under their belts and financing models at their fingertips. Founders need to stay on their toes to make sure they get a fair deal when negotiating their Series A round.

“The devil is in the detail. The intricacies of agreeing things like liquidation preferences were unbelievably complicated,” says David Meinertz, cofounder and chief executive of Zava, the online doctor service, which raised a $32m Series A round earlier this month.

Meinertz is actually a trained lawyer and still found the process occasionally tricky. “It took us about 9 months from first meeting to agreement — which is about average — and although both sides were really focused on getting a deal through there were times when it got a bit tense and rocky.”

The main focus of any funding deal (not just a Series A round) is around the valuation — and most problems stem from getting the valuation wrong. But there are three specific points that tend to catch founder teams out, says Mathias Loertscher, partner at Osborne Clarke: liquidation preference, founder vesting and anti-dilution rights.

Liquidation preference

These are provisions that allow the investors to get back their money — or perhaps a multiple of their money — ahead of other shareholders in the company if the company is sold. It is designed to give investors some protection; they know that even if the company is sold at a distressed price, they will be first in line to get their cash back.

In around 80% of deals the investors simply ask to get back their original investment — often referred to as having one times non-participating shares — says Loertscher. But occasionally they will ask for more — potentially for two or more times their original investment.

It is often a sign that investors think a company’s valuation is too high, says Loertscher. “For example, if a startup is valued at €40m, but the investors think it really should be €25m and would be lucky to grow to €70m before being bought. They might then be looking for additional protection for themselves.”

In 80% of deals investors simply ask for one times their money back. More aggressive terms can mean they think the valuation is too high.

Investors may also ask for “participating shares” — so that they not only have the security of getting their original investment back but will also get any upside the ordinary shareholders get.

There are many variants to play with on these arrangements. Investors could get back a multiple of their investment and participate in any upside but only up to a certain financial value. This is where founders might have to spend some time modelling what different scenarios would look like.

“If it is plain vanilla it can be agreed quickly, but when you have a 2 times participating preference share that starts to scale back once the investor's overall reaches, say 5 times their original investment — then founders need to get their Excel spreadsheet jockey skills into play and work out what they will be getting — it could be less than they expect,” says Loertscher.

Meinertz advises founders to stay alert on the issue. “If you are an investor, why wouldn't you ask for liquidation preferences? It gives you a lot of protection with little downside, you don’t have to give a lot a way.” Founders, however, can inadvertently give away a lot if they don’t read the small print.

Founder vesting

This is one of the most emotionally charged issues for founders, says Loertscher. “This is the point that gets negotiated the most.”

Vesting sets the schedule at which the company’s founders “earn back” equity in their company, usually over several years.

It is fairly standard investor protection measure in venture funding deals and is designed to stop founders from simply walking away from the company the day after a funding round is concluded. A typical schedule is a one-year “cliff” before any stock vests at all and then monthly vesting over the next three years.

Having their share in the company locked up in this way can be a bitter pill for founders, however, especially after they have already sweated night and day for years building the business.

“You may have founders who have already invested in the business for many years, both in terms of time but also their own money. They would have a strong argument for not having all their shares subject to a vesting arrangement. They may want to have 30% or 40% of their shareholding ringfenced, so that it is theirs even if they burn the company down,” says Loertscher.

An additional annoyance is that the vesting schedule often resets each time there is a new funding round, meaning founders are required to lock up their shares again and again.

The Farewill team managed to get around the four year period — a little — because they had already reset it when they raised a seed funding round a year earlier.

“We reset the vesting period in the seed round so that we wouldn’t have to do it again in Series A. Otherwise you will find that investors will ask for you to start the 4 years again,” Garrett says.

Whenever I see the phrase ‘subject to customary vesting procedures’ a little alarm bell goes off in my head.

While vesting timetables may be fairly standard, what may be more tricky is defining what happens to their shares based on why the founder has left the company. If a founder voluntarily resigns, for example, can they keep all or part of their shares, sell them at fair market value, sell them for a nominal price, or simply give them up?

The concept of whether you are a “good leaver” or a “bad leaver” becomes crucial. Bad leavers may lose most of their shares or get little value for them. The trick is defining what exactly constitutes being a bad leaver. It may mean just those leaving the company because of gross misconduct or poor performance. Or it could be anyone who resigns for any reason. Worth checking.

Sometimes companies will argue that managers who leave the company need to surrender their equity so that it can be given to a new, incoming senior executive, but Loertscher says it is worth pushing back on this:

“While companies do need new equity for those situations, there is a discussion to be had as to whether it needs to come solely from the leaving manager,” he says.

Few deals fall apart because of disagreements over vesting, Loertscher adds. “Most founders accept that it is a risk and the cost of raising money.” All the same, it is worth making sure the details aren’t overly punitive.

“Whenever I see the phrase ‘subject to customary vesting procedures’ a little alarm bell goes off in my head and I tell my clients not to sign until they have got this part right,” he says.

Anti-dilution rights

Another difficult detail is anti-dilution rights. These are another investor protection that specifies what happens if the company is forced, later down the line, to raise money at a lower valuation.

For example, if investors put money in at £5 a share in one round, but in the next round shares are being sold at £3 a piece, anti-dilution rights would mean that the original investors are given additional shares to compensate.

Dilution is suffered by the founders who not only have to raise money at a lower valuation but have been kicked in the teeth with much lower ownership of the company than they anticipated.

“It is complicated and lots of founders gloss over the details,” says Loertscher. “It is one of those areas that founders don’t always model and understand.” In the flush of their first Series A fundraising founders may not want to consider the prospect of a down round further down the line.

But the fact is, that any extra shares handed out to investors will come at the expense of the founders and other ordinary shareholders.

“The dilution is suffered by the founders who have not only had to raise money at a lower valuation but may feel they have been kicked in the teeth with much lower ownership of the company than they anticipated,” says Loertscher. In fact, it can be so demotivating for a founding team that investors sometimes waive these rights for fear it will create ill will.

If anti-dilution rights are being put in, Loertscher says it is worth negotiating to make sure the compensation is calculated according to a 'broad-based weighted average’ — meaning that the number of additional shares issued is based on the overall number of shares and not just the price per share on the new fundraising— and that investors are given new shares on a “pay to play” basis. That is to say, they only get the compensation shares if they put money into the follow-on round.

Overall advice

Ultimately, most of the Series A negotiating sticking points come back to valuation. If a negotiation is bogged down with too many unreasonable investor demands, it is worth asking whether the company valuation is simply too high.

“Smart founders have got the joke that creating a valuation that is troo high creates a rod for your own back. It is better to start with something more humble and show steady progress than to be forced to raise money in a down round,” says Loertscher.

Also, says Meinertz, it helps to have several suitors to increase your negotiating power.

“It is really helpful to have competition for the deal and to let investors know that there are other interested parties,” he says. “Obviously only say that if it is true. Whether you are in London, Berlin or Amsterdam, these are pretty small circles and people will know.”

A good lawyer with a lot of experience is essential, adds Garrett. Ted Dewhurst of Kesteven helped the Farewill team and Garrett says he was instrumental in calling out anything abnormal in the termsheets.

“He knew all the investors and could just spot any funny business, tell them to take it out.” It is somewhat ironic that Farewill, whose will-writing service is replacing some conventional legal work, find itself, in this case, indebted to a lawyer.

“I can’t tell you how much I normally hate lawyers,” Garret laughs. “But in this case, Ted was brilliant. I love him. I actually love him.”

This piece was amended to reflect the fact that Ted Dewhurst advised Farewill through his own business, Kesteven, rather than through Harrison Clark Rickerbys.