This is the first part of a series mapping the European startups challenging Elon Musk’s empire. Part 2 is about the hyperloop, Part 3 is about space tech, Part 4 is about neurotechnology, and Part 5 explores ways to overcome a fragmented Europe.

At $390bn, Tesla is worth a lot to investors. In fact, it’s worth more than all of Germany’s carmakers combined.

Europe started out as the birthplace of the automobile, but it has become the laggard — and not just as far as stock market valuations go.

In the 12 years since Elon Musk released his first full-electric sports car, he’s expanded into battery production at Tesla’s Gigafactory, deployed dedicated charging infrastructure worldwide and developed products that let consumers generate and store energy. His Roadster has become the reference for super-fast travel on a battery and his electric sedans have climbed the rankings to compete with Nissan for the world’s most sold electric car.

In that time frame, prestigious brands in Europe, the likes of Volkswagen and Daimler in Germany but also Renault and Peugeot in France, have mostly struggled with a diesel emissions scandal and displayed a sluggish attitude to shifting to battery-powered cars.

Pessimists say the fate of European carmakers shows the region’s inability to transform even the most brilliant ideas and finest engineering talent into disruptive innovation at scale.

“It’s not lack of vision that is plaguing Europe — carmakers like Renault have long had the vision of a future with electric, connected and autonomous vehicles,” says Francois Veron, the cofounder of investment fund Newfund. “But they failed at industrialising that vision, at adapting their production and supply chains to the new business models of electric cars.”

“Real disruption is more likely to come from an independent player than from the incumbents,” says Veron. “A heavily financed independent player.”

But while Europe does not have a single Tesla equivalent, it does have several companies doing parts of what Tesla does and in many cases doing it better.

Without the media might of the Musk empire, they are less well known, but there are companies such as Rimac making faster electric roadsters, companies like Skeleton Technologies making more powerful ultracapacitors and Einride making electric self-driving trucks.

Here’s part one of our series looking at Elon Musk's empire and the European technology companies emerging as its rivals.

Want to go deeper? These are the 9 European startups that show us the direction the car industry is taking next. Click here to read.

Part one: vroom

Cars are one of the most visible parts of Tesla, and make up the majority of its revenues. In the second quarter of 2020, car sales accounted for 86% of its reported $6bn sales. A newly launched Model Y has got car pundits salivating.

But perhaps the most emblematic of Tesla’s successes lies in its ability to deploy a wide-spanning network of dedicated, ultra-fast chargers called superchargers. They’ve played a key role in helping Tesla’s cars stand out from the rest, by addressing consumers’ fear of running out of juice in an electric vehicle.

In fact, infrastructure that allows for a relatively short charging pit stop along the way is perhaps the only segment where Tesla truly has no equivalents in Europe.

The company boasts nearly 2,000 stations in Europe and the Middle East. Alternatives, even added together and helped by state subsidies, form a smaller network of disparate chargers that are all less powerful — hence slower to refill a battery — and are often faced with compatibility issues.

Every other part of the electric car ecosystem has Europeans in the ring, battling it out with Tesla. Here are the names worth knowing:

Tesla’s hypercar challengers in Europe

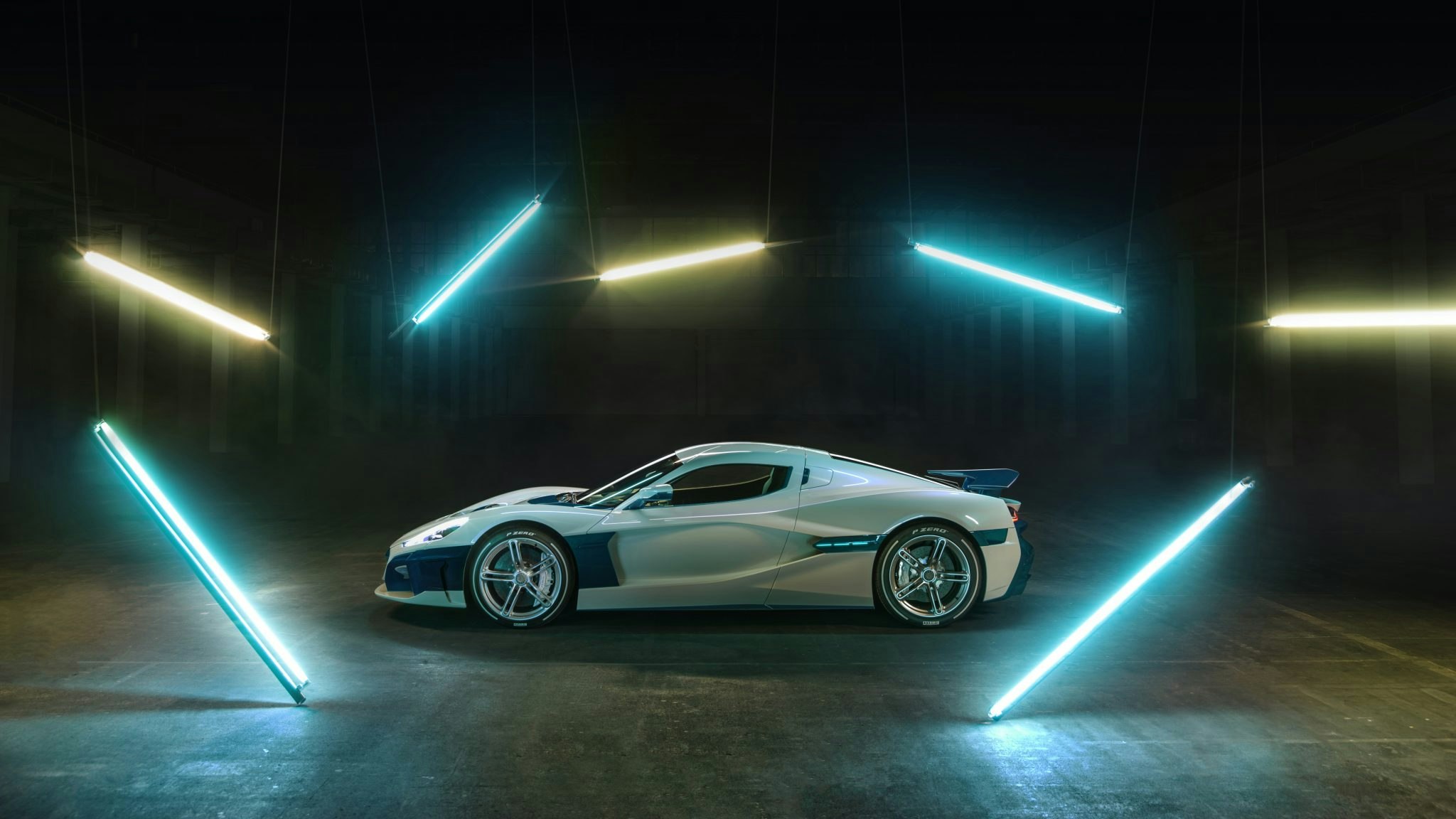

Rimac (Croatia)

Tesla’s Roadster makes claims on being the quickest car in the world. According to the company, it’s able to go from 0-60 mph in just 1.9 seconds, and has a top speed of more than 250 mph.

Croatia’s Rimac may be able to just pip Tesla’s record, with claims that its C_Two electric hypercar can accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in 1.85 seconds, a whisker faster than the Roadster. And the C_Two claims a top speed of 258 mph.

Mind you, Rimac’s C_Two isn’t in production yet. Any prospective customers will have to wait for 2021 to take delivery, and there are likely to be only a very limited number of vehicles made. Your likelihood of owning a C_Two is probably a lot lower than owning a Roadster.

Rimac, which began with Mate Rimac trying to pimp up his own very beat-up 1984 BMW when he was just 19, is clearly a very different (and much smaller) business than Tesla. But its mission to build electric motor cars that are, well, super fast, is having a surprisingly big reach across the car industry.

Porsche owns around 15% of the company, and Hyundai Motor Group recently invested €80m as part of a new partnership which will see the two companies collaborate on a range of performance electric cars. A number of other carmakers, including Aston Martin and Pininfarina already use Rimac’s battery packs for their own electric supercars.

With serious investors coming in now, Rimac is professionalising and gearing up to go much bigger. Plus, it just recently hired ex-Tesla engineer Chris Porritt as CTO.

Piëch (Switzerland)

Piëch is based in Switzerland but it has deep roots in Germany and links back to Volkswagen.

The company was founded by Toni Piëch, the son of former Volkswagen chairman Ferdinand Piëch, whose own ancestors include Volkswagen founder Ferdinand Porsche.

It’s out to build on Germany’s history of top-notch engineering, combined with an electric motor and reviving iconic elements of classic sports car designs, to become the “leading luxury electric mobility brand”.

“In spirit, we go back to Ferdinand Porsche’s 1931 vision,” the company says on its website. “We aim to build a company that recaptures the artistry, craftsmanship and heritage of the past, but we emerge into 21st century with a new powertrain, a new business model, and an appetite for technology and disruption.”

The company’s Mark Zero all-electric model, scheduled to go on sale in 2022, can get to 100km/h in 3.2s, charges 80% of its battery in 4 minutes 40 seconds, and boasts a range of 500km on a single charge.

One specific: Piëch has no plans to invest in its own manufacturing and relies instead on a network of partners for production — carmakers with factories, assembly and supply chains already set up.

Nikola (US-based, with ties to Germany and Italy)

The other, much-hyped challenger to Tesla is Nikola.

Admittedly that’s partly because of the name of the company, which refers to Nikola Tesla, the engineer and inventor who made important contributions during the 1900s to what we know about electrical supply systems. His surname inspired Musk’s company, and Nikola of course picked up on his first name.

Nikola is going head-to-head with Tesla in electric trucks. The company is US-based, but it does have a big European connection.

Germany’s Robert Bosch and Italy’s Iveco, the truck-maker backed by the Agnelli family, each own 6% of Nikola and were instrumental in building the important parts of the company’s trucks.

More than 200 Bosch employees were involved in building important parts of Nikola's trucks, including the electric motor for the axle, the vehicle-control unit, the battery and the hydrogen fuel cell. The trucks themselves are being built in an Iveco factory in Germany.

Tesla’s trucks challengers in Europe

The Tesla programme for trailer trucks, dubbed Tesla Semi, has been pushed back a bunch of times and the first units are now expected to be delivered sometime in 2021.

Einride (Sweden)

Stockholm-based Einride’s trucks are not for consumers, but for the logistics industry. The company started off focused on developing self-driving trucks that would transport goods entirely autonomously or controlled remotely. Recently it has acknowledged that the transition to full autonomy may take some time, so it is also building trucks that have space for human drivers.

The trucks will still be all-electric, however, and deals with big companies may do more to speed along the battery-powered revolution than any consumer-focused business. Einride recently signed a deal to supply trucks to German supermarket group Lidl, supporting Lidl’s ambition to make its supply chain emission-free.

Others include:

Volta Trucks (Sweden)

The company recently launched a purpose-built 16-tonne electric truck that can drive up to 200 km on a single charge. The company is expecting to sell 500 of the Volta Zero trucks in 2022, rising to 5000 by 2025. It is expecting to find strong demand in cities like London and Paris where diesel vehicles have been banned from the city centres.

Tesla’s Gigafactory challengers in Europe

Musk called the Gigafactory “the machine that builds the machine” — where everything needed by Tesla would be made, most notably a huge number of lithium-ion batteries for its vehicles. Tesla has three such factories in operation so far, in Nevada, New York and Shanghai, with a factory near Berlin expected to be completed next year.

The idea of the Gigafactory was not only to decrease Tesla’s reliance on overseas suppliers of batteries but bring the cost of production down to under $100 per KWh of energy storage, a level at which it becomes cheaper to build an electric powertrain than an internal combustion engine.

The Nevada Gigafactory had a goal of producing 35 GWh per year by 2020. Opened in 2016, the Tesla facility has a clear head start, but in the past year or two a number of challengers have emerged in Europe:

Northvolt (Sweden)

One of Europe’s biggest battery startups was founded by ex-Tesla employees. Peter Carlsson, who was global head of sourcing and supply chain at the company, worked closely with Musk to launch the Model S. Another Tesla alumnus, Paolo Cerruti, helped Carlsson launch Northvolt, which is building a giant battery factory in northern Sweden, aiming to produce 32GWh of capacity annually — just short of Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory levels — once it is fully up and running. The company raised $1bn last year from investors led by Volkswagen and Goldman Sachs.

Carlsson says that while China and the US have been in the lead so far when it comes to producing the batteries needed for electric cars, Europe now has an opportunity to catch up.

“At present, we don’t have enough factories but looking at the projects being planned and constructed as we speak the future looks promising in Europe,” he says. “In Europe, there is a new momentum. We have seen actions in the regulatory space and Europe has started to flex its muscles by backing and financing car manufacturers and others along the supply chain – and the dynamics are strong. To be frank, the US has lost a bit of headway between the shift from Obama and Trump.”

“Europe now has to decide whether it will focus on satellite factories that rely on supplies from Asia or will it build its own ecosystem. There are advantages to the region to have its own ecosystem with all the actors across the supply chain including subcontractors, factories, support to universities and so on.”

“Strategically, it is possible to build it but we don’t have it ready for raw materials as yet. We have the conditions to create nickel and cobalt but it will take time. We are not alone, even in China they are dependent on building supply chains of raw materials, just look at what they are doing in parts of Africa and South America.”

In the meantime, Northvolt is developing patent-protected ways of recycling batteries more efficiently, so that part of Europe’s raw material needs could be supplied this way.

Verkor (France)

The startup exited stealth mode and unveiled ambitious plans to deliver up to 50GWh of battery production capacity. Production in Verkor’s first gigafactory is scheduled to begin in 2023 with 16GWh capacity and ramp up from there.

Backed by French industrial Schneider Electric, real estate group IDEC and the EU’s European Institute of Innovation & Technology (EIT), Verkor is currently looking for land to set up a gigafactory in France. The initial investment in the project is about €1.6bn.

It’s not the only French project of the sorts. Energy giant Total and carmaker PSA have set up a joint venture called Automotive Cells Company, which is also aiming to start deliveries in 2023. The first phase of the project involves a €200m investment and a pilot plant built around an existing facility in Nersac, France, owned by Saft, Total’s battery production arm. Total took over startup Saft in 2016 for €950m.

Fast charging

Europe is also developing breakthrough technologies that could significantly increase the charging speeds for electric vehicles. Charging an electric car at a public charging point can still take several hours — even a Tesla Supercharger station will take at least half an hour — so getting charging times down to a point where they can compete with a few minute petrol refuelling stop is crucial.

Ulracapacitors, which discharge energy much faster than batteries, have been seen as a potential part of the solution. Tesla bought ultracapacitor company Maxwell Technologies for $218m in 2019, in hopes of improving the batteries used in its cars. Battery experts speculated that Musk might be looking to apply some of the technologies used in Maxwell’s ultracapacitors to improve the cost, performance and lifespan of its lithium-ion batteries.

Skeleton Technologies (Estonia)

A European challenger, Estonian Skeleton Technologies, may be close to this already. The company is developing the SuperBattery, a ground-breaking graphene battery with a 15-second charging time and the capability of being recharged hundreds of thousands of times.

The company has just partnered with the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology to complete the development of the battery. If this is successful, it would eliminate the three main anxieties of electric car owner: slow charging time, battery degradation over time, and limited range.

Skeleton Technologies chief executive Taavi Madiberk says the technology will “blow existing EV charging solutions out of the water”. He also notes that, unlike Tesla, which seeks to do everything itself, in Europe the key to energy storage breakthroughs will be a collaboration between companies.