In Part 3 of our series mapping the European startups challenging Elon Musk's empire, we look at those who are battling it out with SpaceX to conquer a flourishing “new space” market. Part 1 is about cars, Part 2 is about the hyperloop, Part 4 is about neurotechnology, and Part 5 explores ways to overcome a fragmented Europe.

SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk in 2002, shows what can be achieved if you take spaceflight out of the hands of governments and leave it for entrepreneurs to figure out.

In less than two decades, SpaceX achieved technological leaps that have spurred nothing short of a global revolution in the space sector.

It’s made European entrepreneurs and policymakers green with envy. How could they have, once again, have been so outclassed by a US tech company?

But while Europe still looks irredeemably behind the curve in some core areas such as launchers, the space race is changing — and the continent is in a position to create the next generation of spacetech leaders.

OneWeb, the satellite internet company, is one area where Europe still has the edge over Elon Musk, now that the business has been rescued from bankruptcy by the UK government and Bharti Global, the Indian telecommunications group.

Both OneWeb and Musk’s Starlink, which is part of SpaceX, are looking to fill the sky with hundreds — maybe thousands — of low earth satellites to beam internet access over every part of the globe. But OneWeb has the priority rights for the Ku-band of satellite spectrum that will be used for it, giving it an advantage.

There are also new opportunities emerging in the launcher and nanosatellite space, as well as new businesses opportunities to exploit space data and use it for new applications, from the internet of things to driverless cars.

Many of Europe’s most promising startups are focused on these emerging parts of the market, which are often broken up into categories of: new launchers, data, downlink technologies, analysis and new products.

Exotrail, for instance, has specialised in satellites that can shift position once they are in orbit, and D-Orbit offers a “space taxi” service that makes it cheaper to get a microsatellite into exactly the right bit of space. Others like Arqit and Nu Quantum are harnessing quantum know-how to make sense of the tsunami of data being generated by fleets of newly deployed satellites.

True, no single company is beating Space X right now with its combination of technological wizardry, money and marketing might. But all empires fall. Which European tech companies are vying to steal its crown? Who is challenging the Musk space empire?

European investment growing fastest

The backdrop to all of this is that — in part thanks to Space X making space exploration and exploitation more affordable — global investment into spacetech is growing. And, recently at least, it has been growing in Europe fastest of all.

According to the Seraphim Space Index, last year was a record year for the space industry, with global venture investors increasing their investment in the sector by 21%. Total VC investment rose to $4.1bn during the year up from $3.25bn (2018) and $2.5bn (2017).

While Europe has had a slower start, investment in space this year has been growing faster than anywhere in the world. Over the past year, total investment into US-based space companies fell by 20% to $2.29bn. In Asia, it was up 25% to $531m. And in Europe investment was up 56% to $276m.

“Europe is leading the way for an appetite to invest in this area,” says Mark Boggett, managing director at Seraphim Space Ventures, a London-based venture fund dedicated only to investing in space companies.

There are new Venture Capital funds as well. Just last month, OTB Ventures announced the launch of a fund dedicated to Europe’s leading space technologies, backed by the European Investment Fund and the European Commission.

“We've been looking at this industry for quite some time and we’ve always looked at this as a real growth opportunity,” says Adam Niewinski, one of OTB Ventures’ managing partners.

OTB has already two investments in two space-tech companies, Finnish microsatellite startup Iceye, which recently raised €74m, and SpaceKnow, a space data startup that was founded in Prague and still has its research centre there.

“Probably back three years ago when we were looking at it it was more of a long-term vision, because commercialisation and the revenue traction was at the beginning,” he says.

“Now we know that spacetech can actually generate money and can actually provide good solutions not only to governments but also for commercial clients.”

US wake up call

The interest from investors comes at a time when Europe can’t afford to hesitate. With SpaceX leading the way, in recent years the US has gained a competitive edge in core areas.

By successfully landing the base of a SpaceX rocket in 2016, Musk’s company proved for the first time it’s possible to reuse a rocket over several missions, drastically cutting the cost of carrying an object out into space.

The event is one Jean-Yves Le Gall, head of French space agency CNES, equated to “a giant wakeup call” for Europe.

“Six to nine months ago, many in Europe thought Elon Musk was just hot air, even among the big shots in the space industry,” Le Gall said. “But he showed he was able to do it, to potentially reuse rockets one day. He’s clearly shaking things up.”

Change in attitudes

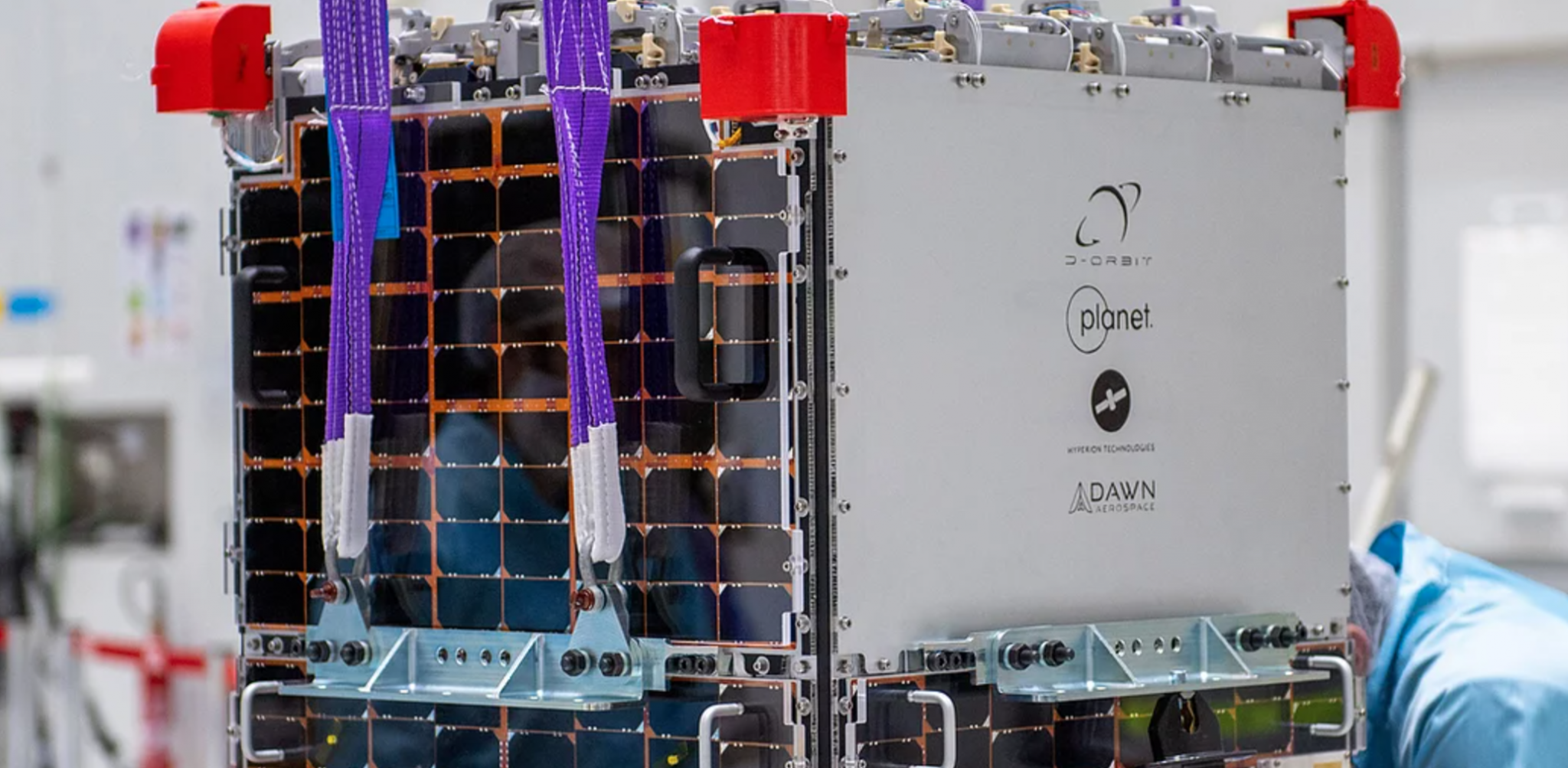

There has been a notable change in attitudes towards space investment in Europe over the last decade, says Luca Rosettini, founder and CEO of D-Orbit, an Italian company specialising in a “space taxi” service, ferrying microsatellites into the precise orbital positions they need.

When Rosettini, who had briefly worked at the US space agency Nasa, first started talking to the European Space Agency and European investors about his company in 2011, he used to have to tone down the more ambitious parts of his presentation.

“Returning to Europe I quickly learned that you couldn’t be seen as too much of a visionary if you wanted to be taken seriously,” he tells Sifted, “I learned that I had to talk just about cleaning up space debris, not my whole vision for space transport. Nine years ago the institutions were still really sceptical.”

Now, he says, things are changing and organisations like ESA have become more willing to back new ideas. D-Orbit is concrete proof of this. Rosettini has two framed letters on his office wall, both from ESA. A letter from 2011 is a rejection letter, telling Rosettini his idea is science fiction and urging him to return to school to study the physics of space flight. The second letter, from 2019, warmly congratulates him on winning the bid.

“They are both for the same project. It just took 8 years to convince them,” Rosettini laughs.

The year before, OneWeb caused a stir when it announced it was planning to launch 900 micro-satellites in low orbit to create a global internet. That opened up the possibility of using satellite communications in new ways.

Since then, launching a satellite into space has gone from being an expensive, highly regulated and complicated affair, and a service sold to a handful of customers including broadcast television stations, to miniaturised hardware and launching into space more often.

European catchup

Now, Europe is looking for its own milestone demonstration.

Europe lags far behind SpaceX in terms of reusable rocket launchers. In June, France’s CNES and Safran Airbus Launchers unveiled an engine that would make the Ariane 6 rocket reusable and slash 75% from the current cost of sending a payload into space. But it will only start to be tested this year.

Last year, the European Investment Bank (EIB) flagged the region as a laggard in many respects and called for more investment, especially on satellites and launchers.

Still, the EIB report said that European companies can catch up by making good on the region’s cutting edge innovation on key parts of the space spectrum: expertise in the likes of nano and micro-electronics, and communications (which are discussed in more detail below).

“There’s really an untold story of innovative companies in space, companies below the radar because of their size and also partly because of the fragmentation of Europe,” the EIB’s head of innovation finance advisory Shiva Dustdar tells Sifted.

“We don’t have our SpaceX, mostly because Europe’s big problem is scaling.”

A problem of scale

For Iceye’s founder Rafal Modrzewski, the root of the problem in Europe is about customers.

“You can quite easily track SpaceX’s customers by looking at SpaceX revenue. The vast majority of it comes from the US government. It's either NASA, Department of Defense, or other governmental bodies,” Modrzewski says.

Modrzewski argues that it will probably take SpaceX another decade to become a commercially driven company. In Europe, with the lack of government agencies buying services from the local space startups it is difficult to grow.

“From our perspective, as a company, one of the hardest things of growing up in Europe was the fact that most of the customers that we are selling to are, unfortunately, not European,” he says. "That would be something to look into, why European customers are not buying from the European companies in the early days.”

“Our biggest customers are actually South American and North American governments, and they will actually rather have us there than in Europe,” he adds.

Brussels is stepping in with financing

To help address that fragmentation, the EIB has been handing out loans and lending hybrid capital including some equity. It’s not quite the same as being one giant customer like the US government, but it’s a start.

Through its European Investment Fund (EIF) arm, it has also invested directly in space funds and startups, though the end goal is to mobilise private investors.

To do that the EIB has set up a space financing lab, offering some hand holding into the specificities of the sector for less specialized investors. The lab brings investors and startups, as well as policymakers and people from the European Space Agency (ESA), together to better address the financial opportunities, says the EIB’s Dustdar.

“Sometimes less specialised investors feel like this sector is a place for the billionaires’ toys, or all about going to the moon. But there’s so much more to it,” he adds.

The next investment areas

Startups building hardware, like rockets or satellite constellations, are already getting a lot of attention, and other neglected but key areas are likely to attract the next wave of investment, says Seraphim Space Ventures’ Boggett.

“The next area is the efficient movement of data from the satellite to use on the ground,” he says. He estimates that over the next few years there will be some 35,000 satellites in orbit, from some 180 companies, and the amount of data collected from space will expand dramatically as a result — and all of that data needs to be received and extracted on the ground.

The EIB has a similar analysis.

“Space is increasingly becoming an enabler of digital — of data,” says the EIB’s Dustdar. “Lots of money has gone into hardware already in Europe, with programmes like Copernicus and Galileo. The infrastructure is there and so much data is already being generated in space, but now we need more companies to create business models around that data.”

OTB Venture’s Niewinski points to analytics as something his team believes can be a strong side of Europe’s space-tech ecosystem.

He also adds that the rise of microsatellite startup Iceye could act as a catalyst for the European space ecosystem as a whole, with one strong player pushing the whole region into a different league.

The European startups challenging Space X

Exotrail (France)

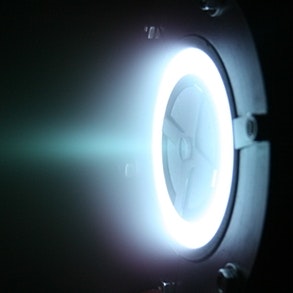

The startup raised €11m in July to keep developing its miniaturised electric propellers and software aimed at making small satellites better deployed, more efficient and less polluting. Part of that involves allowing the satellites to shift positions once they’re in orbit to prevent collisions and avoid debris.

“Our recent funding round was in line with what comparables in the US are raising,” David Henri, Exotrail’s chief executive, tells Sifted, adding that there was a strong presence in the round from European investors.

“More broadly, I don’t think it’s fair to say Europe is very late relative to the US — if you compare space budgets for the two regions, Europe has actually been efficient,” he says.

So what’s missing in Europe? Governments in the region should hand out more contracts to startups and rethink their procurement strategies to support up and coming local innovation more, says Henri.

The topic has been coming up a lot in France, in the defence sector as well as at an event between company founders and president Emmanuel Macron last month. Increasingly, the view from founders is that what the ecosystem needs most isn’t more funding from the state, but rather more business and contracts being handed out to them.

Exotrail has 27 employees and a goal to grow to 50 people by 2022 in order to be able to produce 100 propulsion systems per year.

Iceye (Finland)

Iceye, founded in 2014 in Finland, deploys radar satellites that collect images of the surface of the Earth at any time of day, in any weather conditions. With its microsatellites and SAR technology it has been able to compete with large corporations like Airbus, Atlas and Maxar, due to the fact that when using a constellation of small satellites it is possible to provide data with higher frequency and latency.

The startup has 200 employees and raised €74m from Newspace Capital, Seraphim Capital, Draper Associates, DNX, Draper Esprit, Space Angels and OTB Ventures last month.

Arqit (UK)

Focuses on quantum encryption for space, which some argue will be central to really getting the most out of space technology. One investor André Pienaar, founder of C5 Capital, a specialist venture capital firm focused on investing in cybersecurity and artificial intelligence, wrote recently: “Space and cybersecurity are inextricably linked. Space is the future of cyber.”

Nu Quantum (UK)

Nu Quantum produces quantum machines that can emit, as well as detect, single-photons. They are working with Arqit to use this for quantum encryption for space communications. Space is not Nu Quantum’s primary business focus, but their super-sensitive photon-detection system could also play a role in deep space communications, which are likely to be done using lasers rather than radio waves. The company has just raised a £2.1m seed funding in a round led by Amadeus Capital Partners, which will go towards building a state-of-the -art photonics lab in Cambridge.

NanoAvionics (Lithuania)

Founded in 2014 as a spin-off from Vilnius University, NanoAvionics is a nanosatellite equipment manufacturer and mission integrator focused on satellite buses and propulsion systems.

The company already has over 75 successful satellite missions and commercial projects under its belt. It was awarded €10m by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 and ESA’s ARTES and private investors in late 2019 for the precursor stage of its Global Internet of Things (GIoT) nano-satellite constellation, which will form an interconnected network with 72 satellites aimed at IoT and machine-to-machine service providers.

In August the company announced that it had tripled its revenue over the previous 12 months, after signing contracts with multiple government agencies and commercial entities. These included contracts to build a pair of cubesats for a consortium of Dutch and Norwegian government agencies working on an experimental military program, five nanosatellites to capture ultra-high-definition video from space for British video-streaming startup Sen, as well as work on two prototype satellites for Thales Alenia Space. In June the ESA awarded NanoAvionics €1m to develop key components for its small satellite propulsion systems.

Zero 2 Infinity (Spain)

Developing high-altitude balloons to provide access to near space and low Earth orbit using a balloon-borne pod and a balloon-borne launcher instead of the usual rocket.

Isar Aerospace (Germany)

The Munich-based startup founded two years ago is aiming to launch its first rocket by the end of 2021 to transport small satellites into low orbit around the Earth.

D-Orbit (Italy)

The company offers a unique “space taxi” service, ferrying microsatellites into the precise orbital positions they need. It is bridging a gap in the market — large rocket launches can get more satellites into space at one time, making them more cost-efficient. But the satellite end up all in a very similar spot and end up having to find ways to manoeuvre to their final position.

“If you land at Heathrow Airport, you don’t pack your car with you on the plane so you can drive to the hotel. You take a taxi. But we are still, essentially, packing a car onto a rocket to get the satellites into place. It is very expensive,” says D-Orbit founder and CEO Luca Rosettini.

D-Orbit offers to be the “taxi” that gets satellites the last part of the journey, and can also help with de-orbiting old and broken satellites at the end of their lifespan.

“We can reduce the time from launch to being operational by 85% and we can cut launch costs by 40%,” says Rosettini.

The startup, based in Como, Italy, launched its first satellite carrier from the Guiana Space Center in French Guiana, on an Arianespace launcher, last month, and has at least two launches lined up for next year.

At the moment it is the only company offering services like this, although a number of competitors are starting up in the US, says Rosettini.

Kineis (France)

KineisThe startup is developing a constellation of 25 nano satellites built specifically for nternet of things connectivity. In areas that aren’t as well covered by earth-based communications networks, like 5G wireless bandwidth that transits through antennas, businesses would instead connect to Kineis’ satellites.

The offering is tailored to customers on fishing, freight, or even leisure boats that are out at sea in open waters. It can also be used to track flocks of animals —camels in the desert aren’t in the best position to catch a good wireless signal— or scientists studying sea turtles.

Founded in 2019, Kineis had €5m in sales the first year, and raised €100m in February 2020. The plan was originally to send it into orbit in 2021, but that’s been pushed back a year.

Orbex (UK)

Orbex provides an orbital launch service to small, micro and nano satellites customers, but with a twist - claiming that they are more eco-friendly than others. The company uses bio-propane, which it says is a “clean-burning and completely renewable fuel that also reduces carbon emissions by 90 percent compared to conventional rocket”. fuels.

PLD Space (Spain)

PLD, founded in 2011, is developing two partially reusable launch rockets.

It closed a €7m investment deal last month, as part of a broader fundraising that added up to more than €18m previously. It’s using the money currently to develop MIURA 5, an orbital launcher built for the small satellite industry.

Anywaves (France)

The startup makes miniature antennas for small satellites. Anywaves was selected last month by Thales to help supply US company Omnispace with telecommunications nano satellites aimed at Internet of Things (IoT) applications sometime next year.

Isotropic (UK)

Isotropic has technology to make satellite terminals more efficient. It has raised money from Boeing’s venture arm.

Gomspace (Denmark)

GomSpace is a manufacturer and supplier of nanosatellites for customers in the academic, government and commercial markets. Founded in 2007, it's services include systems integration, nanosatellite platforms and miniaturised radio technology.

MT Aerospace (Germany)

MT Aerospace is a big company creating subsystems for the European launch vehicle ARIANE.

Isispace (Netherlands)

Innovative Solutions In Space is a Dutch NewSpace company based in Delft dedicated to the design, manufacture and operation of CubeSats. The company is one of the market leaders in Europe on the nano-satellite domain. ISISpace has supported the launch of 367 satellites on multiple launch vehicles as of October 2019.

AAC Clyde Space

AAC Clyde Space builds nanosatellite spacecraft, mission services, and subsystems. The company was formed after Sweden’s AAC Microtec bought UK miniature satellite maker Clyde Space in 2017.

Other

Other notable spacetech companies in Europe include; Swissto12 (Switzerland), Open Cosmos (UK) SnapPlanet (France), Kleos Space (Luxembourg), ConstelIR (Germany), Hawa Dawa (Germany), Methera Global (United Kingdom), Trik (United Kingdom), Veoware (United Kingdom) and Hiber (Netherlands).