In 2040 your ultimate status symbol might be your bicycle — and the fact that you aren’t suffering from type-2 diabetes. Slow culture — no more commuting to work — showing off about your health, a culture of green consumption and maybe a fear that your car might get hacked have consigned the automobile to the periphery of our lives.

We may be living in smart cities which know where we are at any given time — we may even be microchipped for access to various areas — and pervasive government nudges will direct how we move about.

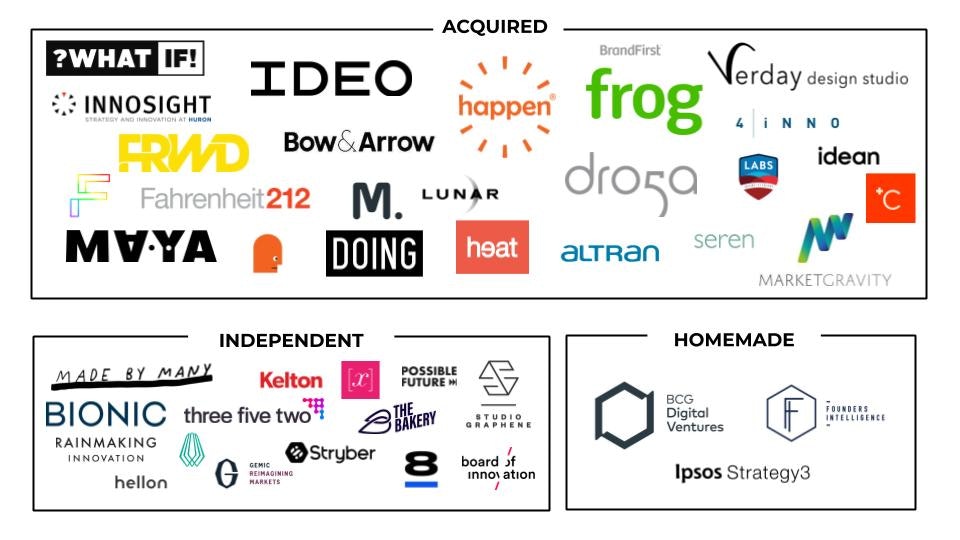

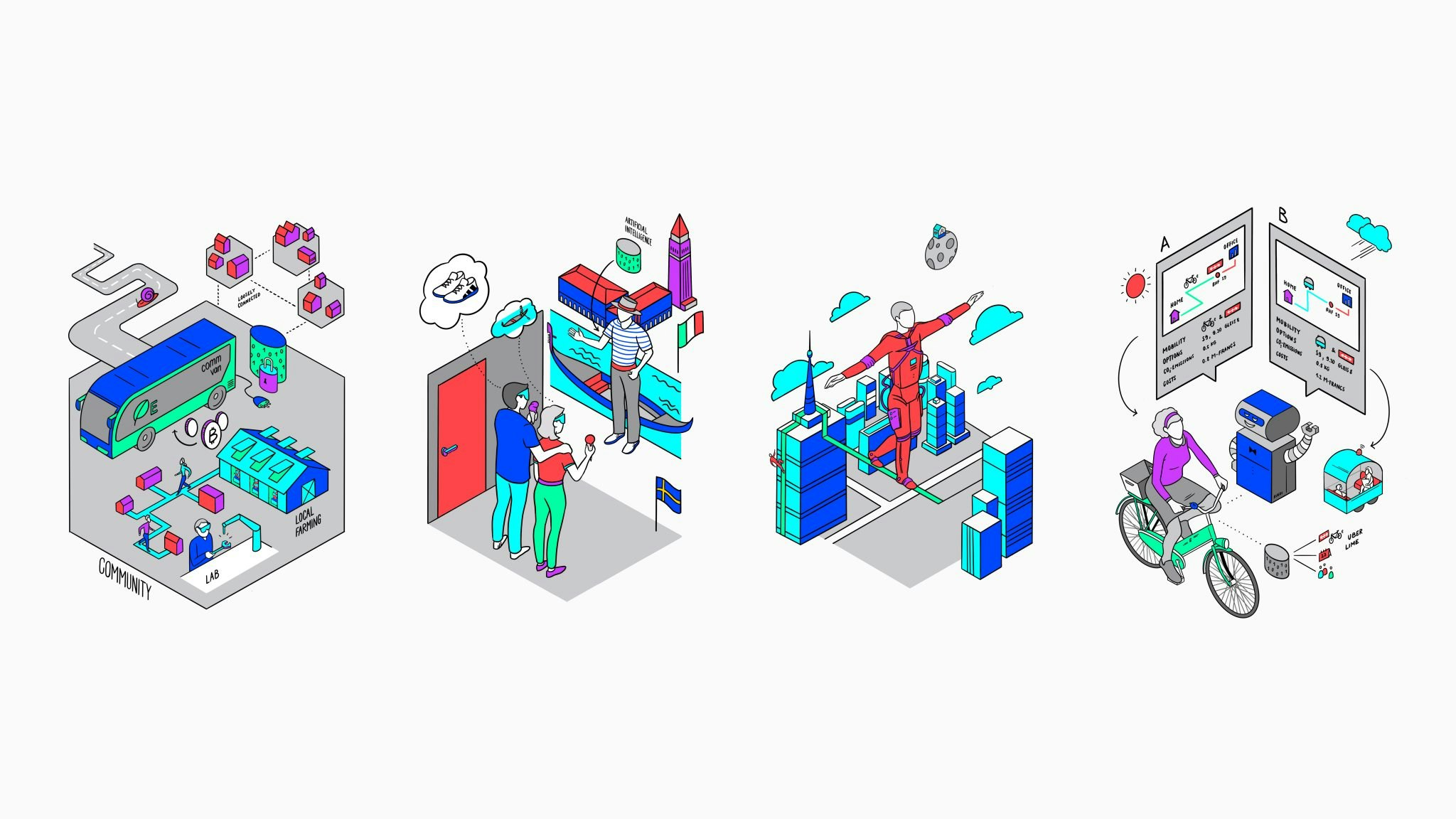

Spark Works, the Swiss innovation consultancy undertook a somewhat “Black Mirror”-like exercise mapping out a series of potential scenarios — in varying degrees utopian and dystopian — to predict how we will be moving 20 years from now.

It is an exercise that more companies should do, says Alan Cabello, cofounder of Spark Works. Even when companies plan for the future, too often they look just five years out. For really big investment decisions, that is too short a horizon.

“Look at autonomous driving. Companies like Mobileye, which was bought by Intel [for $15bn in 2017], have been working in this area for 20 years,” says Cabello. “Imagine someone telling you twenty years ago that autonomous driving was going to be a thing. It would have seemed very far-fetched. But it would have been a smart investment.”

Spark Works spoke to 76 industry experts from corporations, public institutions and universities to create a really long-range forecast for mobility. Future Proof caught up with Cabello to find out what the project taught them.

How did the project come about?

We created this report for Baloise, the Swiss insurance company. They are interested in investing in mobility-related startups but were looking for a different angle and a way to evaluate opportunities more effectively.

Mobility is a very crowded market with all sorts of tech advances that can be hard to put into context. As part of this report we built Baloise a tool that would show them how near a startup was to a certain number of future trends. A startup might be strong in relation to one trend but not address any others, the tool would help put that in context.

Baloise are actively using it to evaluate investments, it is their “secret sauce” so to say. That part isn’t available to anyone else, but the report itself is free for people to read.

What was different about the methodology of this report?

A lot of reports are all about tech and looking usually five years ahead. We asked experts not about the next five years, but to look 20 years out. It became much more of an interesting philosophical question. Leading experts had very different opinions, especially in areas like AI, but we mapped all of this to get a sense of the direction we might go.

We also looked at society and human behaviour more than just technical development — what does it take to nudge people to use a different form of mobility?

Society and human behaviours are really the determining factors in how we adopt technology. For example, unless you get society to feel more comfortable with self-driving cars and you have the political lobbying power to get governments to allow them, we will not see them on our streets.

There is a really big question about who really changes society. It is no longer the government. The speed of change now is such that politics can’t keep up. It is often companies and society that are getting in first to make changes. In the late 90s Nike stopped using sweatshops to make its clothes and shoes, not because of government legislation but because of consumer boycotts.

So what surprises came out from the analysis?

Just how interconnected everything is! None of these trends will happen in a vacuum, and their impact will always trigger another trend, some positive and some not so much.

As for individual trends, some of the biggest surprises were on the political side. Trends like cyberwarfare — for example hacking autonomous vehicles — were really worrying because we are not really very well prepared for these.

The trend of hyperindividualism was also interesting. If everything becomes tailored to individuals do we lose our sense of community? At the same time, there is also a trend towards localisation which could counteract that.

From the technology standpoint, the biggest issue we saw was about power and how to manage it, for example figuring out batteries properly. If we manage to crack power storage, that will be transformative.

You started a lot of this research before the Covid crisis began. Is the report out of date?

Actually, after the crisis, many parts of the report sound very familiar. Some of the trends we identified in our study have become a reality during the crisis. For example, we talked about how flights would become unavailable for most people, tourism would become more local and people would travel mostly on campervans. This sounds familiar doesn’t it? Through the Covid crisis we have seen just how quickly people’s behaviour can change if you take definitive action.

The report was designed to be a far-off look but now it seems like these future scenarios might only be five years away.

How did Baloise react to the predictions?

They liked the tool a lot. The scenarios they found interesting. Something interesting was how strongly they reacted to the Swiss scenario; it probably got the most negative feedback. Maybe that was because, being Swiss, it felt too close to home. Whatever the reason, this is the purpose of these scenarios, to elicit conversations, brainstorm and even plan what we would do if such a scenario or parts of it were to happen.

Did you feel this was a useful exercise in the end?

Yes. We wanted to put an idea into managers’ heads, so that when they were evaluating an opportunity they would see it in a different context to what they are used to every day. As well, when difficult situations arise, and they do, managers are perhaps better prepared to handle them having in the back of their minds these trends, scenarios and their consequences.

Some of the big companies like Shell, BMW and Volkswagen have futurists who will do this kind of research, but not many others or medium-sized companies undertake it.

If every company did an exercise like this, they would be better prepared for crises like the one we are facing now. For smaller companies in the same industry it would perhaps be useful for them to work together on imagining what life might look like in 20 years. The future will always be uncertain, but it does not mean we cannot be better prepared for it.

You can read more about the study on the Spark Works blog.

Spark Works has also published a free tool that helps organisations think through "unthinkable" future scenarios. You can download it here.