In six years' time we will be travelling across town by flying taxi, almost as easily as we now get an Uber. And not too long after that, these taxis will be flying us autonomously, without pilots.

This at least is the vision of Lilium, the Munich-based startup that doesn’t want to make expensive toys for billionaires, but fundamentally change the way we all travel.

Lilium is fast becoming one of Europe’s most talked-about tech companies. It ticks pretty much every box when it comes to a compelling tech story:

Cool product

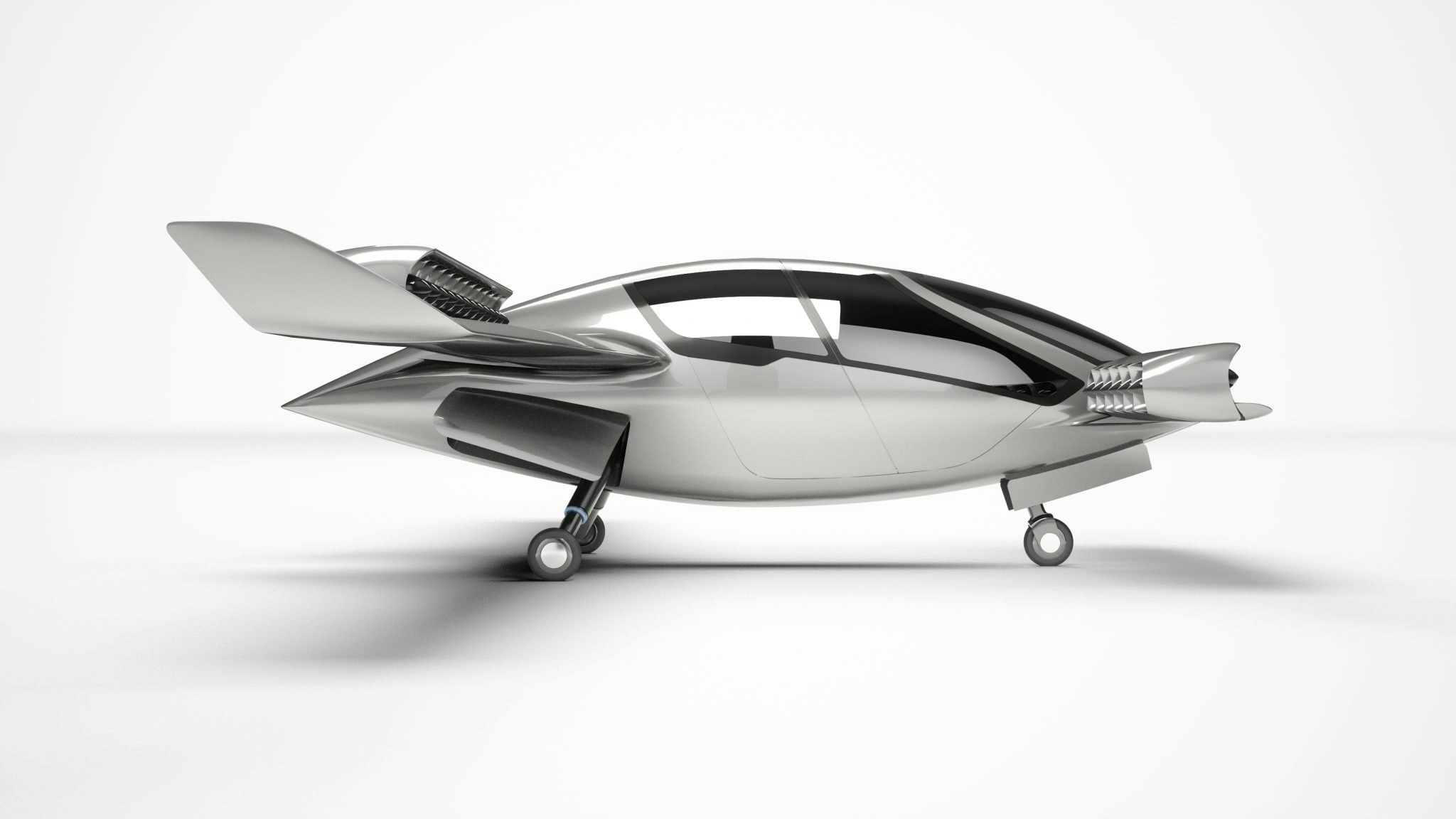

Lilium is making one of the world’s first all-electric vertical takeoff and landing jets. It is taking the kind of ‘jump jet’ technology that the military has been using for some time but making it cheaper, quieter and more eco-friendly by using electric engines.

The engines swivel downwards to lift the aircraft off the ground, then move to a horizontal position to push it forward like a conventional aircraft,

An egg-shaped, two-seater prototype plane took to the skies in 2017 and the company is now building a five-seater version which it is expected to unveil later this year. Lilium says the plane can fly for an hour on a single charge, covering 300km in that time. That’s faster than a Formula One car (although slower than a commercial airliner).

The first planes will be piloted but the long-term plan is for them to fly autonomously. And they will, eventually, have the aesthetic of luxury cars: Lilium last year hired Frank Stephenson, designer of the Ferrari F430, Maserati MC12 and the new Mini, to design the planes.

Young and colourful founder team

The company’s wild-haired cofounder and chief executive, Daniel Wiegand, is a lifelong aviation enthusiast who started piloting gliders at the age of 14 and came up with the idea for Lilium while he was studying electrical engineering and flight propulsion at the Technical University of Munich.

Three friends — engineer Sebastian Born, aerodynamics specialist Patrick Nathen and mechatronics engineer Matthias Meiner — joined him to found Lilium Aeronautics in 2015. The name is a tribute to Otto Lilienthal, the German aeronautics pioneer.

Big money

The company has raised a total of $101.4m from investors, making it one of the best-capitalised startups in this sector.

Big name investors

Frank Thelen, a German serial entrepreneur and investor, famous for his appearances on Germany’s version of the Dragon’s Den TV show was an early believer and investor in 2016 — despite some mockery.

“I received calls and emails from other investors and even friends asking if this was a joke or if I wanted to experience failure again. Some sent me articles about failed aircraft projects, while others (seriously) offered me a bed and food for a year,” Thelen writes in a blog post describing the early days of Lilium.

Next Atomico, the venture capital fund run by Skype founder Niklas Zennstrom, led a €10m Series A round. A $90m Series-B round in September 2017 brought in investors including Tencent, the Chinese internet company.

Lilium not only won financial backing from Atomico — the company poached one of Atomico’s partners, Yann de Vries, who joined the company as VP of corporate development.

Big ambition

Lilium intends to build a global flying taxi service, accessible for everyone — a kind of ‘Uber of the skies’. Remo Gerber, Lilium’s chief commercial officer, believes the company can create a whole new mass transport category: urban air mobility.

“Ultimately this opens a different paradigm in connecting places,” Gerber says.

But can it work?

There is no doubt about Lilium’s outsized ambition. But what are its chances of success?

Sifted caught up with Gerber. His role is a combination of being a chief financial officer and a chief operating officer. Remo joined the company in 2017, two years after it was founded, and is the business face of the company, the “grown-up”; Lilium’s version of Eric Schmidt at Google.

Gerber, who was previously managing director for Europe at Gett, the ride-hailing company, is the man who will turn an engineering project into a flying taxi platform.

The business model

For all the Jetsons futurism, the idea of flying cars is starting to be taken increasingly seriously. Morgan Stanley estimated in a report last December that the market for autonomous urban aviation mobility (aka self-flying taxis) would be worth $1.5tn by 2040.

Gerber makes it clear that the taxi service idea is central to Lilium.

“We’re not intending to make it a luxury product that only the rich can buy. We want to make it a service that everyone can use,” he says.

Even if you offered him a huge sum, Gerber says he would not sell you an individual plane.

“We wouldn’t sell you a plane, no — but we would suggest you work with us to develop a landing pad for the entire village or community near where you live, which could also serve your needs.”

It is not that Lilium has a particularly socialist outlook.

In fact, most of the companies developing flying cars are leaning towards the mass transport service model. In part, this is because it may well be easier to get all the regulatory approvals they will need from air safety officials and municipal authorities when there is a strong public-good argument for the service.

One of Gerber’s themes is that the Lilium flying taxi service will help cities cut the cost of moving people around. In contrast to multi-billion dollar tunnel, bridge or rail-link projects, many of which have faced delays because of spiralling budgets, Gerber says that a series of flying taxi landing pads could be built for half a million euros.

“This is an opportunity to look at alternatives to costly infrastructure projects,” he says.

We’re not intending to make it a luxury product that only the rich can buy. We want to make it a service that everyone can use.

But the taxi platform is also about economics.

Morgan Stanley believes the economics of flying taxis could be far more profitable than road-based ride-hailing services like Uber.

They take the example of a 20-mile Uber ride, which takes on average 48 minutes and costs $30. On a busy day one Uber car might do 10 such trips, earning $300 or $75,000 a year. A flying taxi, however, could cover the 20 miles in 12 minutes and earn a small premium for the speed — say $50. It could do 40 such trips a day, earning $2000 or $1.5m a year.

This lucrative calculation does rely on a couple of assumptions: 1) companies get permission for flying without pilots on board (more on that later) and 2) that battery technology improves enough to keep the flying taxis in the air for eight hours a day — or that it is feasible to have a big bank of spare batteries to swap in and out of the aircraft. At the moment Lilium can only fly for about an hour, or 300km (186 miles), on a single charge.

Running a service platform — as well as building all the planes for it — will also be quite a stretch for a young company, even one that has now grown to 300 people. It will be a bit like being both Airbus and British Airways at the same time.

Gerber is convinced it can be done — and that in the beginning it is essential for Lilium to control all elements of the experience.

“We want to build the best customer experience. We want it to be simple and seamless so we are heavily involved in owning the whole customer journey,” he says.

The competition

There are at least 19 companies developing versions of flying cars.

These include some of the biggest names in aviation, such as Boeing, which bought Aurora Flight Sciences last year to speed the development of its autonomous flying vehicles. A prototype completed a successful test flight in January.

Airbus has developed a vertical take-off aircraft called Vahana, and is experimenting with on-demand helicopter booking service Voom in Brazil. Defence contractors like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman are also developing technologies like these. The military has, of course, for years already had vertical take-off or ‘jump-jet’ technology.

Then there are all the big names in tech.

Uber recently announced plans to launch a flying taxi service by 2023, and Bell (formerly Bell Helicopter) is one of a number of companies understood to be developing aircraft for it. Google founder Larry Page is backing the Kitty Hawk project, which has raised $9.5m in seed funding so far and is testing aircraft in New Zealand.

Terrafugia, a US-based company owned by Chinese automaker Geely, started taking orders in October for the Transition, a vehicle that transforms from car to aircraft by unfolding a pair of wings. Chinese drone-maker EHang is creating an autonomous passenger-carrying quadcopter.

In Europe AeroMobil in Bratislava is developing a sports car with wings, and Stuttgart-based Volocopter plans to start testing its vertical take-off craft in Singapore this year, having raised €31.2m from investors including Intel and Daimler.

The closest competitor is probably Joby Aviation, however. The Californian company has raised the largest amount of funding among the flying car startups, some $131m, and its backers include Toyota AI Ventures and Intel.

One of Lilium’s advantages over rivals is the long range of its jets — 300km — thanks to a highly energy-efficient design. Once airborne the jet flies much like a conventional plane, using the aerodynamics of its wings. Competitor aircraft that function like giant hovercraft can only fly shorter hops.

Joby, however, comes close to matching Lilium’s range, with 150 miles (241km).

Gerber says there is room for a number of competitors in the market.

“We hope it will be an open ecosystem with ports and landing spaces serving several companies.”

Regulation

By far the biggest question is regulation. Gerber is confident that manned versions of Lilium’s jets will be able to get certification as light aircraft, a fairly straightforward process.

However, moving to autonomous flight would require completely new regulation from safety bodies such as the Federal Aviation Administration in the US and EASA in Europe.

“They are progressive and will look into this. But it is a chicken and egg situation. They will want to see more results from testing these aircraft first,” says Gerber.

2025 is a date we are confident about.

Aviation regulators are getting a lot of invitations to flying car conferences at the moment as companies like Uber strive to get them onside.

But an exchange between Dan Elwell, acting administrator of the US FAA, and Uber’s head of product, Jeff Holden, at the Uber Elevate summit last year was telling. Elwell shot down, in no uncertain terms, a proposal by Holden to create a separate air corridor that Uber’s flying cars could use between Dallas and Fort Worth.

Then there are considerations of noise and privacy which may make it difficult to get permission to fly in many city areas. Although electric jets are designed to be much quieter than helicopters, they are not completely noiseless. A Lilium jet has about the same noise level as a truck when it takes off. The prospect of giant-sized drones overhead may be unpalatable for many city residents.

Still, Gerber is predicting that the first “meaningful” Lilium taxi services could be available by 2025 — in just six years’ time.

“Of course there are no guarantees,” he says. “But we are making very good progress and it is a date we are confident about.”