As the “most startup friendly” country in the world, Latvia’s tech ecosystem has boomed over the past decade — and a key sector of growth is deeptech.

This year was dubbed the “year of deeptech” by investors across Europe. So far in 2022 Latvian robotic tech developer Aerones has raised a $9m round and engineering platform CENOS has raised another €1m.

“A deeptech is a company where a big part of the business is based on the innovation coming from universities,” says Egita Aizsilniece-Ibema, head of the Latvian office for innovation and technology in Brussels. “It requires intellectual protection, it requires lots of testing and lots of pre-investment in the first phase in order to realise the product into the market.”

But Latvia is a small country with a population of under 2m people, so what does the deeptech industry really look like — and what are the roadblocks Latvian startups face?

1. More than one in ten Latvian startups and scaleups are in the deeptech sector

According to Dealroom, 13% of Latvian startups and scaleups founded since 2012 are in deeptech. Aizsilniece-Ibema says the sector has become a particular area of interest for the country because it’s looking to develop products and services that can be exported globally.

“The administration of Latvia is looking at areas where we have great potential to add value to our exports,” she says. “We don’t have internal markets, we only have external markets as we are a small country, so our companies from birth have to look outside and think global.”

As part of this, Latvia has built up five areas of specialisation in deeptech, Aizsilniece-Ibema adds — smart materials (particularly photonics, the science of generating and manipulating light), biomedicine, smart energy, ICT hardware and bioeconomics.

“Currently I’m helping a very good company that’s building a pea protein factory that should be the biggest in the region, so alternative proteins can solve the problems of the future of food supply,” she says. “And historically our pharmaceutical industry is very strong in the region coming from the Soviet times, so we are building on that experience.”

We don’t have internal markets, we only have external markets as we are a small country, so our companies from birth have to look outside and think global

Aija Pope is CEO and cofounder of TerraWaste, a “non-recyclable plastic waste recycling company that strives to create new climate-positive materials through a pollution-free process”. She says her startup was built in response to the climate crisis.

“Due to the climate crisis, the need for cleantech and deeptech startups has increased and the ecosystem in Latvia is very active, supportive and still growing,” she says. “There is a wide startup network and a great opportunity to connect with industry players and relevant funding institutions.”

2. More and more young Latvians are getting degrees

According to the Official Statistics of Latvia, the levels of education in the Baltic country have been increasing since the 1950s, with every second young woman in Latvia now holding some form of higher education.

For Liene Briede, director of the science and innovation centre of Riga Technical University (RTU), this has helped the deeptech sector boom.

“In Latvia, there’s a huge coverage of educated people,” she says. “So a lot of educated people, including PhDs, can use the knowledge and can continue to do scientific work with Riga’s industry.”

Briede adds the startup ecosystem is being utilised more and more to commercialise scientific products.

“There’s a big shift and transformation from the classical scientific process to commercialise it and especially using startups as an instrument to commercialise scientific results,” she says.

However Pope says for her startup, which requires niche scientific knowledge in a certain area — which deeptech startups often do need — finding talent is a challenge in such a small scientific community.

“We don't have a lot of chemists that would be available for collaboration, nor knowledge in the sphere that is crucial for our development,” she says.

3. Slower to grow, but potentially more lucrative in the long run

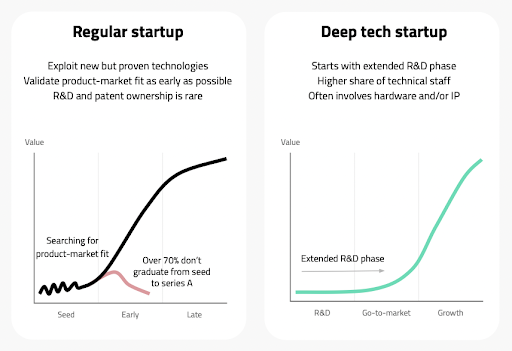

One of the main differences between deeptech startups and other tech startups is the time it takes for products to be commercialised, as deeptech starts with long research and development periods. This can impact funding, particularly VCs who are more focused on “the quick game”, says Aizsilniece-Ibema.

“For [deeptech], it takes eight years from an idea to something so that’s quite a long time and these eight years have to be financed by something,” says Briede. “It’s challenging for the investors to be more risky, to have this long-term investment… This is quite important because the return on investment will not be so fast, but will maybe be really valuable in the end.”

Pope agrees, saying one of the main roadblocks for deeptech startups in Latvia — and beyond — is funding.

“There is a huge gap between the initial funding and the next stages,” she says. “As the deeptech startups can't cross this gap within the first six months of their development as by default the development road map is longer than, for example, fintech or application generating startups.”

For [deeptech], it takes eight years from an idea to something so that’s quite a long time and these eight years have to be financed by something

Ilona Gulchak is chairperson of the board at the Commercialization Reactor Fund, a fund that brings together scientists with non-tech entrepreneurs in Latvia. It aims to alleviate the funding challenge and also has two funds.

“We work with different universities in different countries, not just in Latvia, sourcing scientists with brilliant ideas and different technologies and we bring them together with external entrepreneurs,” she says. “The scientists, they stay in the labs, they are in charge of developing the technologies, but the external entrepreneurs, they do business development.”

4 … but there is investor appetite

However, investor appetite for deeptech has been steady in Europe — even if it does take some convincing.

“If there is scientific proof of development and the capabilities of the technology, then definitely there are a lot of investors who are interested,” says Pope. “But it takes a rather big effort to convince the investors to actually meet past the first stage, as they are not really keen to invest in too early-stage startups.”

Latvian startups can also raise money from European funds, says Aizsilniece-Ibema. One example is Lightspace Technologies, which got a grant from EIC.

“One that has done great at the European Innovation Council is Lightspace Technologies,” she says. “It’s virtual reality glasses applied in various fields currently, they test in healthtech, but they also see potential in automotive and other directions.”

Another resource for deeptech startups in Latvia is Deep Tech Atelier, an annual event in Riga.

“The differentiator of other events is really that it brings the business side and the research side in one room in one space,” says Aizsilniece-Ibema. “It brings together two worlds that don’t often talk to each other.”

Keep track of the startup ecosystem news on deeptech and other sectors by subscribing to the monthly newsletter.