Yesterday morning at Isar Aerospace’s headquarters in Munich, the company’s first rocket engine — built entirely in-house — rolled off the production line.

“It was a big moment for us,”says Daniel Metzler, the company’s CEO — and it was an even bigger moment for Europe’s space sector.

Small rocket launchers are predicted to become a €30bn market by 2027 — and, with an exclusive new partnership alongside Norwegian rocket launchpad Andøya Space, Isar is well positioned to take advantage of that.

The money in micro satellites

Founded in 2018, Isar Aerospace builds micro-satellite launchers — otherwise known as carrier rockets — that are smaller and lower in price than bigger launchers on the market.

Metzler says the company — a spin-off from the Technical University of Munich –—is “testing and integrating” four launch vehicles to transport small satellites into low orbit around the Earth. It plans to launch its first rocket in mid-2022.

In December last year, Isar raised a Series B of €75m led by VC firm Lakestar — the largest round to date in European space tech — bringing its total funding to €90m.

Launching a satellite into space, however, is a complicated business. It requires a whole launch system — including a launch vehicle, launch pad, vehicle assembly and fueling systems, and other related infrastructure.

At the moment, there is not yet any low orbital launchpad in mainland Europe, says Metzler.

Typically, satellite manufacturers launch their satellites from the US, India, Japan or Russia, which is costly and involves “a lot of hassle” in terms of logistics, and import and export control.

But now, with exclusive access to Andøya Space’s launchpad on the northwestern coast of Norway, Isar can launch rockets far more easily for the next 20 years.

“For us, it’s super important to have a launchpad in mainland Europe which is closer to our production site,” says Metzler.

“The exclusivity [of the agreement with Andøya Space] provides us and our clients with maximum flexibility and planning security to bring satellites into Earth’s orbit at any time. It enables us to provide long-term turnkey launch solutions from European soil.”

A growing market

Over the past five years, space technologies have gone through a process of ‘miniaturisation,’ says Metzler.

Whereas a satellite six to seven years ago used to weigh upwards of a tonne, the smallest satellites — Cubesats — weigh just 1kg and are 10cm in length on each side.

“That’s a fully-fledged satellite that you can have orbiting the earth at 500km in altitude, delivering some sort of service or connectivity,” says Metzler.

Access to space has become decidedly more democratic in the last five years, continues Metzler. Today, satellites are simpler and cheaper to build than ever before, and all the necessary components can be purchased online.

Mini satellites are quite literally like rubik’s cubes in size, says Paul Klemm, principal at Earlybird, the Berlin-based VC firm that co-led Isar’s Series B round.

In theory, any company can build them and combine them with others to create their own constellations in the sky.

“As the space industry moves from larger, single satellites to constellations of smaller satellites, the market for small rocket launches is forecasted to grow,” says Klemm.

“This is due to numerous applications for small- and medium-sized satellites and satellite constellations — from businesses in industries from transportation and logistics to mobility."

Whereas demand for satellite data used to be fueled by governments for security, defence or weather forecasts, companies are increasingly requiring data for asset tracking, smart farming and GPS — as well as for garnering insights on climate change and natural disasters.

I see our technology as an enabler for innovation in other industries.

Large demand for Isar’s technology is also coming from the German automotive industry.

Herbert Diess, CEO of Volkswagen, visited Isar in December to discuss Volkswagen’s plans to connect autonomous vehicles to the internet via satellites in the future.

“I see our technology as an enabler for innovation in other industries,” says Metzler.

He adds: “Imagine what you could do if you were to provide internet via satellite across the globe to continents such as Africa or the Middle East. Having access to the internet is a fundamental human right and nearly half of the earth’s population don’t have that.”

Addressing the satellite launch ‘bottleneck’

Launching satellites into orbit in a timely and cost-effective manner is one of the biggest challenges for the commercial space industry — especially given the surge in demand.

We have customers who are sometimes waiting two to three years to have a rocket flying into the right orbit for them to deploy a satellite.

Available launchers are large and go up into orbit infrequently. As a result, reserving space on them takes a lot of forward planning and investment.

“We have customers who are sometimes waiting two to three years to have a rocket flying into the right orbit for them to deploy a satellite. That’s not a lot of flexibility,” says Metzler.

This satellite launch “bottleneck” is exactly what Isar is addressing.

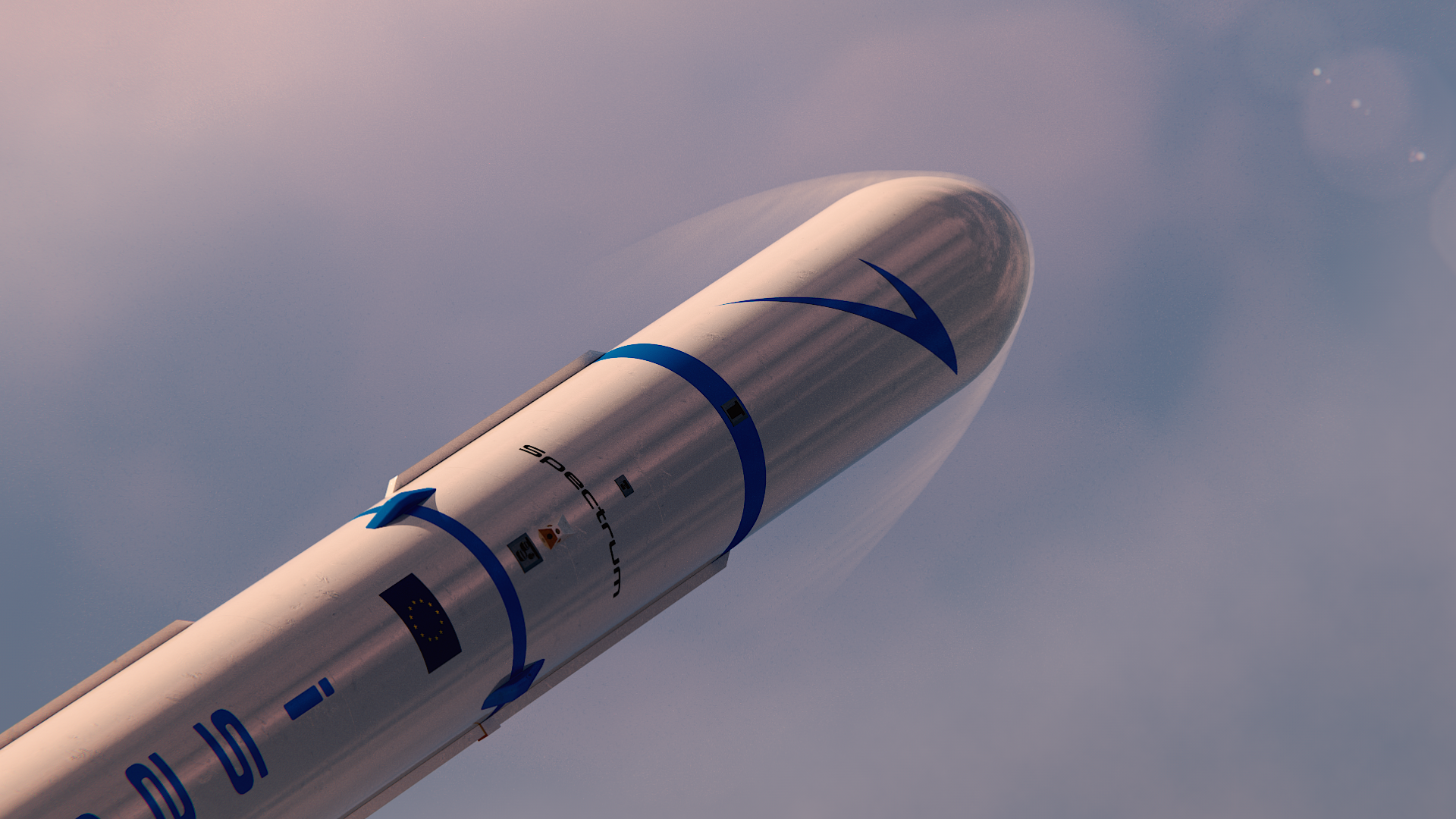

By building launchers that are lighter and thus less expensive, Isar can make it cheaper and easier for organisations to book satellite launches. Isar’s Spectrum launch vehicle will aim to carry a payload of over 1,000kg.

Standing out from the crowd

Isar isn’t the only company in Europe with this agenda. Klemm says that there are as many as 25 European players in the satellite launcher industry.

For example, in Germany, there’s HyImpulse Technologies,which is focusing on building a three-stage rocket with a hybrid propulsion system based on paraffin and liquid oxygen. There’s also Rocket Factory Ausberg — developing a three-stage carrier system based on liquid oxygen and kerosene.

So why did Earlybird choose to back Isar rather than its other competitors?

Klemm says that Isar has a number of competitive advantages. One is that the propulsion system of its rocket uses a lighter fuel than what is typically used in bigger launchers.

“Everybody in the industry is using methane to power their rockets. Musk wants to fly to Mars [with SpaceX], and you can refuel on the Moon to go to Mars with methane — so everyone is following that,” he says.

Isar, on the other hand, is powered by a mix of propane and liquid oxygen which “burns cleaner" – meaning there's less soot during combustion. As a result, it is roughly 80% cleaner than traditional rockets.

In Metzler’s view, Isar has a competitive edge since it uses a simple design and highly automated manufacturing — both of which drastically reduce the cost of each rocket launch.

Future plans

Currently, Isar is focused on developing its business for “low earth orbit bound customers.” But it says it plans to embark upon space exploration missions from 2025.

“In the last few weeks, we’ve received more and more requests about exploration missions like putting a payload into Moon orbit, for example, or even putting a payload on the moon’s lunar surface,” says Metzler.

“But for now, we want to focus on our first satellite launch next year — which will depend on the launch pad in Norway being fully operational by then.”

If the launch is successful, Isar will be the first privately-financed European space company to build a successful satellite launcher.

After that, the company plans to ramp up its launches from one to 25 per year — a “challenge” that Metzler and his team are far from underestimating.

“It’s complicated putting things into space,” he adds.

Miriam is Sifted’s Germany correspondent. She tweets from @mparts_

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Isar could be the first European space company to build a successful launcher. This has been correct to "first privately-financed" European space company.