On the short five-minute walk from Edgware Road station in London to Humanoid’s office, I pass a menagerie of food and drink chains, all staffed by real-life humans. But, if Humanoid has its way, one day they might be joined by humanoid robots.

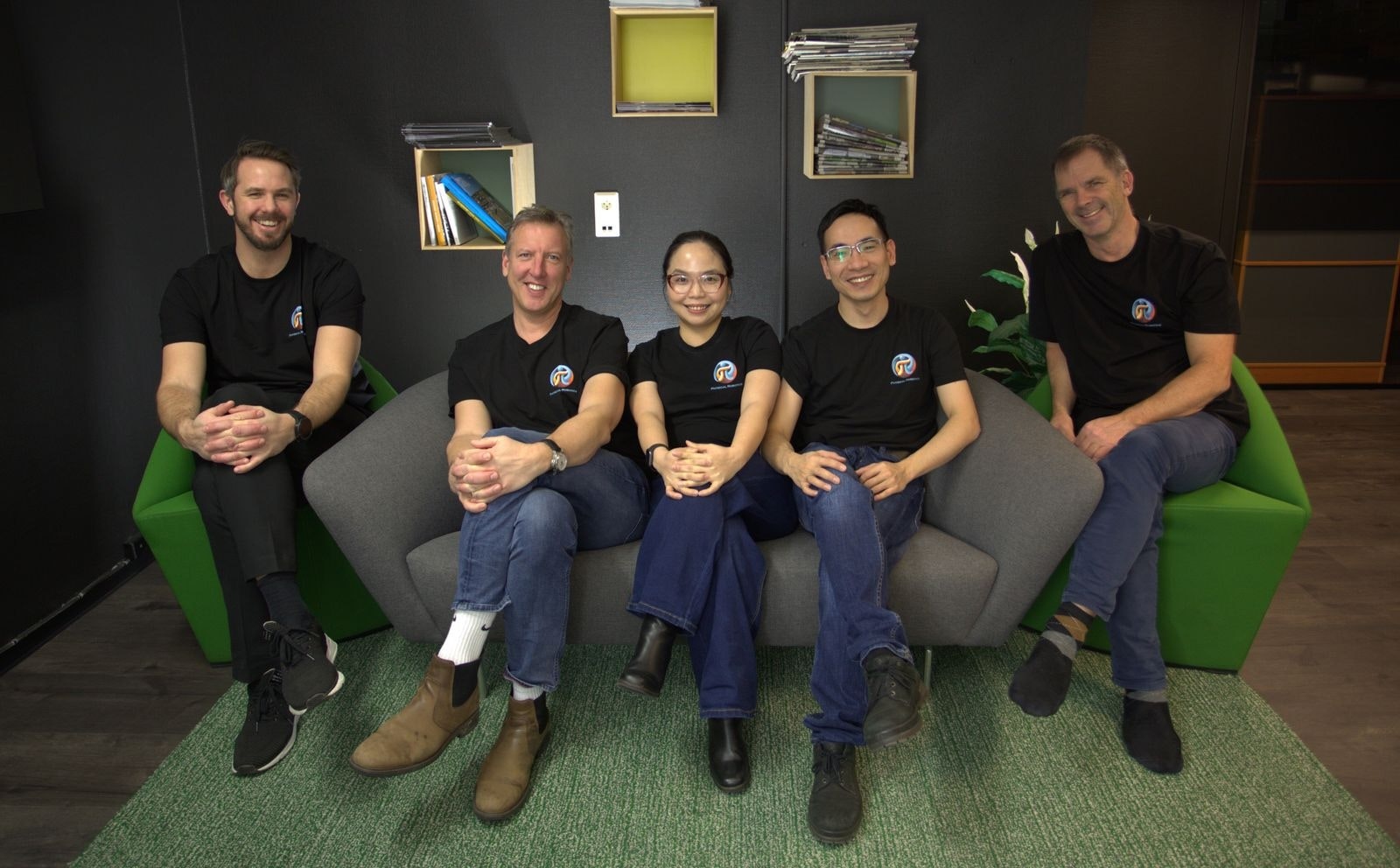

“We do see lots of use cases in the kitchen, for example grilling, frying or dishwashing,” Alina Kolpakova, Humanoid’s chief strategy officer, tells me from the company’s fifth floor WeWork office.

Humanoid, which was founded in 2024, has been funded for the last year by the personal wealth of founder and CEO Artem Sokolov, who’s also the founder and general partner of venture builder SKL.vc. He’s put in around $30m. But the company will soon need a lot more, and is preparing for a Series A.

The long term vision is that we’ll all have our own robot; a piece of personal hardware as indispensable as our mobile phones.

“We’re building the iPhone of the future,” Kolpakova says. “You will have a robot. I will have a robot. We won't be able to live without our robots.”

‘We’re not rushing into households’

When I arrive, there’s an array of salads and snacks laid out in the kitchen. Humanoid’s team have lunch provided for them every day — a perk they get as part of a mandate to be in the office five days per week. Total headcount is 160 split across the London office, and the company’s bases in Vancouver and Boston, where hardware is built.

Kolpakova walks me through a space where initial testing is being carried out. I'm not allowed to take any pictures, but it’s easy to visualise: a WeWork with bits of robot littered all over the place. It’s all very early stage — although the hope is that the company will get its first commercial robot into the hands of industrial customers in early 2027.

It’s building two products: a wheeled version of its robot with a humanoid torso attached to a manoeuvrable stanchion, and a bipedal robot, which has the same torso, plus legs. The company is also in the process of designing what will become its household robot, which won’t be the same as the model it sells to industry.

These prototypes are being built with some off the shelf components and Humanoid’s custom hardware. When the first robots are sold in 2027 Kolpakova tells me they will be 100% Humanoid software and hardware.

The first sales won’t be to consumers, though. “We’re not rushing into households,” Kolpakova says. “It’s the goal at some point, but we will start with industrial applications, then we’ll go to service applications […] and then probably starting from 2030 we will move towards household applications.

“Investors understand that adoption for humanoids in a household environment will be I think in 10 or 20 years,” she adds.

I’m curious why that’s so far off, when companies like Humanoid — and its competitors Boston Dynamics and Figure in the US, and Neura Robotics and 1X in Europe — are all developing robots with use cases in the home.

“It’s because of safety, and because of the risks associated,” Kolpakova says, “and also hardware challenges […] hardware that we use for industrial applications isn’t right for homes.” She points out that a 100kg bipedal robot, loud and clunky, walking inside your home, isn’t ideal.

There’s also the fact that regulation for humanoid robot deployment in the home is nonexistent. “We know that these safety regulations are still evolving and we are expecting to have regulations specifically dedicated to humanoid robots by 2028/29,” Kolpakova says.

The risk is high. Anything connected to the internet is a potential target for hackers. When that’s your phone, or your fridge, that’s bad but not life threatening. When that’s a 100kg humanoid robot, it’s a tad more serious.

Kolpakova assures me that safety is top of mind for Humanoid. I ask who the company’s equivalent of Mike Donovan and Gregory Powell are, the field engineers in Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot series who are flung off to hazardous corners of space to test robots and troubleshoot them when they go awol. His name is Todd Lewis, head of systems engineering at Humanoid, who joined the company in November last year from Agility Robotics in the US.

“Todd’s interest is in functional safety,” she says. “The most reliable and safe systems for bipedal robots are being designed by him.”

The $38bn humanoid robotics market

The industrial market Humanoid is going after could be highly lucrative. According to Goldman Sachs, the total addressable market for humanoid robots is projected to reach $38bn by 2035, with 1.4m robot shipments expected in that time. Industrial uptake is also on the rise, with installations in Europe up 9% in 2023 to a new high, driven by the automotive industry, according to the International Federation of Robotics, an industry body.

There are several markets Humanoid plans to sell into. First it’ll sell robots for manual work in manufacturing, warehousing, logistics and retail. Then it’ll start selling into the service industry from 2029 — where, Kolpakova says, companies are already struggling.

“Warehouses are struggling to find younger people to replace retiring workers,” she says. “People are ageing, people don’t want to do this [type of work]. Gen Z wants to blog or travel, they don’t want to work in a warehouse.”

Humanoid will sell robots-as-a-service, charging clients a monthly fee that comes with maintenance and support from the company. Target customers for that will be asset light retailers, e-commerce operators and warehouses and distribution centres. It’ll also sell robots for a one-off fee, targeting automotive manufacturers and large scale distribution warehouses. The company declined to share pricing.

It’s completed two proofs of concept so far this year with public companies for its wheeled prototype, and plans to complete three more this year. It has also signed a non-binding pre-order agreement covering up to 2,000 units with one international company, and is in ongoing talks with several others. It’s targeting at least 5,000 non-binding and 1,000 binding orders by the end of 2025.

Through the roof compute and no supply chain

There are a number of challenges standing in the way of Humanoid hitting its targets. One is talent — something that will become trickier the more the company scales its headcount.

It’s up against some well-funded competitors. US-based Figure, for example, raised $675m last year from an all-star cast of backers such as Intel, Microsoft and Nvidia. Norway-based 1X raised $100m last year from investors such as EQT and Samsung, after raising the year before from Tiger Global and OpenAI.

Humanoid moved quickly in the earliest days to fill out its C-suite with industry experts. Its first two hires came from shuttered electric vehicle startup Arrival. Dmitrii Rudnitckii, Humanoid’s VP of robotic platform and applications, led autonomous factory production at Arrival; Thomas Shepherd, Humanoid’s chief operations officer, was Arrival’s VP of operational excellence. Other C-suiters boast names such as Boston Dynamics, Tesla and Apple on their CVs.

There’s another challenge the company faces that no amount of talent will be able to overcome: supply chain issues.

“The supply chain for humanoids doesn’t exist,” Kolpakova says. Why? “Because you don’t have any humanoid robotics companies that produce at scale, you have a bunch of humanoid robotics companies that have prototypes.”

It’s for that reason that Kolpakova rejoices when a competitor raises big. “We like when one of our competitors raises or says we’re doing mass production […] because now we’re going to have a supply chain to optimise,” she says.

It’ll also have to find a way to scale without compute costs going through the roof. Humanoid trains its own models using a variety of open-source models — and pays £1m-1.5m per year on compute.

It also needs to develop its edge computing capabilities — which would allow some processing to happen on device (in the robot’s head) and decision making to happen more quickly. At the moment latency is too slow. “Our first proof-of-concept was super long,” Kolpakova says, mimicking a robot moving super slowly.

After our interview is done, Kolpakova takes me back down to the WeWork foyer and I’m on my way back into the London sunshine. I stop off at a cafe to grab a coffee for the tube ride back to Sifted HQ, and watch as the barista chats to and smiles at the man in front of me as he struggles to get his card to work. A thought crosses my mind: How different would their interaction have been if the server was a faceless humanoid?