Raising money from a big bank is generally a no-go for fintech startups. That didn’t put off Swedish fintech platform Tink, however.

In fact, the risky move seems to have paid off: this week seven-year-old Tink raised a bumper €56m to fund its expansion into Europe.

Bringing in a big bank

Tink started off as a consumer app in 2012 helping customers to keep track of their personal finances. In 2016, a new investor, the Swedish bank SEB, was the biggest investor in an €8m funding round.

For fintech companies, to bring in a bank as an investor is basically a no-go, according to people with knowledge in the field.

“For most fintech companies it is an unnecessary risk to raise capital from a bank,” says Ann Grevelius, with 25 years experience of asset management, credit grants and private banking in the Swedish banking sector.

“It limits the freedom and may raise questions from other banks about how such a deal will favour the bank that has invested in the startup,” she says. ”That may very well end up with other banks turning down doing business with the startup.”

But for Tink, the SEB deal did not seem to put other banks off.

A year later in 2017 a number of Swedish banks, the Dutch bank ABN Amro, as well as VC companies Sunstone and Creades, invested €10m in Tink, which became the white label solution for the aggregated data and spending categories for the banks.

But how did Tink get the new banks on board when it already had investment from SEB?

Keeping banks away from the board

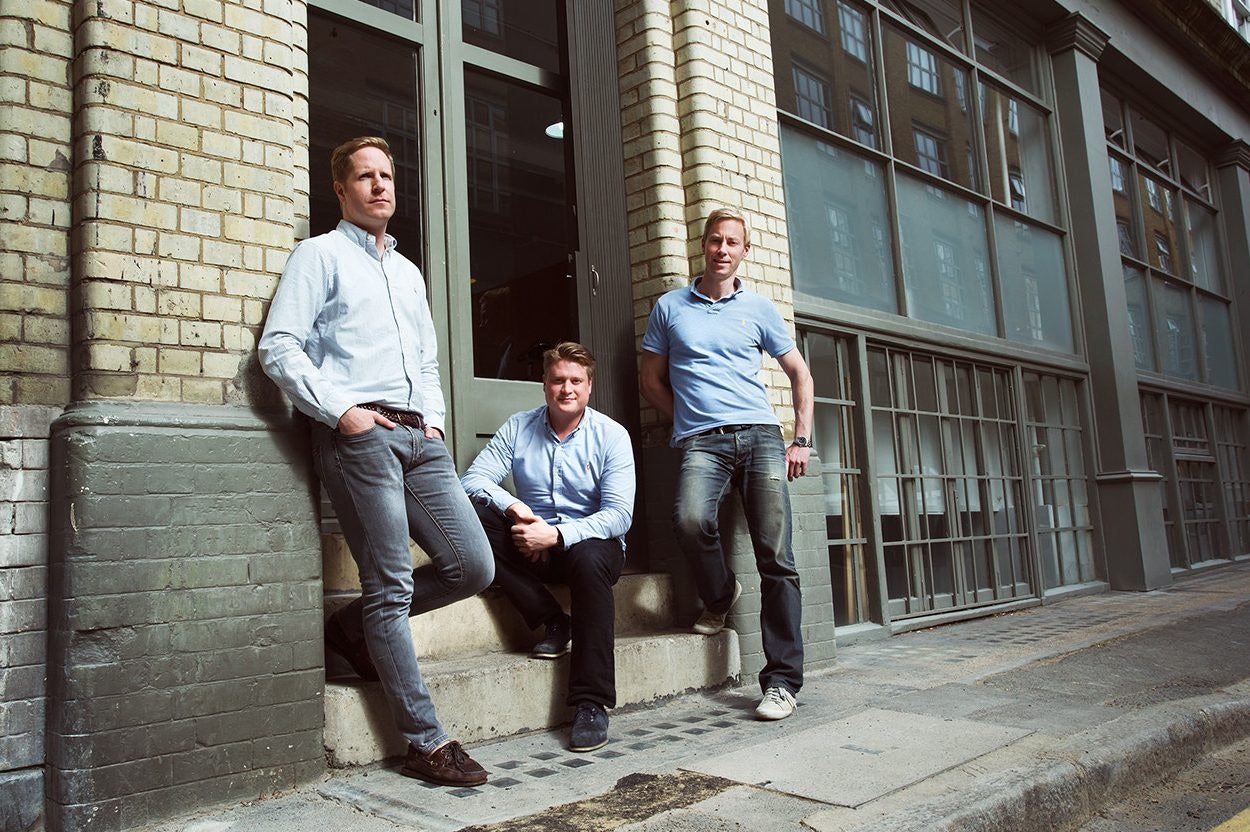

“The initial investment from a bank was obviously a worry that I, [cofounder] Daniel [Kjellén] and the other investors discussed at great length. On the one hand, there was a risk, on the other – the strategic partnerships also gave us leverage,” says founder Fredrik Hedberg.

One very important piece in the puzzle of raising money from banks, he says, was to not give them a seat at the table.

“After some negotiations, we managed to get a deal that didn’t give the banks any representation on the board nor any other additional powers, apart from them obviously being regular shareholders. In that way, we've managed to stay independent.”

When they understood that the banks involved had no extra leverage or insight, then they had to make a rational decision.

Hedberg, whose company is now valued at €250m, is on a shaky phoneline when Sifted reaches him.

“I’m sorry about that. I am in the airport and couldn’t find anywhere quiet so I am in the restroom,” he says.

We asked him if the other banks questioned doing business with them when they found out that they had raised money from a competitor.

“I believe it was a natural skepticism, but when they understood that the banks involved had no extra leverage or insight, then they had to make a rational decision based on the technology that we could offer,” says Hedberg.

Becoming a white label solution

From the original focus of selling directly to customers, all the revenue is now based on their business with other companies (mostly the banks).

We asked if it was too difficult to scale the consumer business, which explains the pivot to selling to businesses. Hedberg argues that focusing on companies, the company can work on their mission at a much greater scale.

“It was a combination of factors. For one, it was another way to capitalise on the very platform that we had built for consumers, but in a business-to-business setting,” he says.

”Our mission has always been to bring transparency to the market and to make it easier for the consumer to understand and manage her money. Being able to leverage our technology in many new markets means that we may affect a billion people in the future — that is fantastic.”