What does a stubbly chin sound like? How does 100 kilohertz of sound feel?

These are not simply poetic questions, they are the basis for a new wave of haptics, which is using the physics of sound waves to give us a new way to interact with machines.

Haptics (from the ancient Greek háptō, to touch) is interaction through the sense of touch. A basic form of haptics has been in the tech industry for more than 30 years, ever since Motorola pagers first started vibrating in pockets to alert their owners. But it hasn’t moved much beyond that. Modern mobile phone screens may shake or provide a sensation of resistance when you 'press' a virtual button, but the range of touch sensations are limited.

“The majority of devices still mostly just buzz,” says Daniel Büttner, the founder of German haptics startup Lofelt. “There hasn’t been much change in haptic technology since 1994.”

Lofelt is trying to take haptics to a new dimension, by borrowing from audio technologies to create much more realistic tactile experiences (read more on this in Lofelt’s white paper) — being able to simulate the feeling of textures like grass, snow or wood.

The company is able to map the swishing, scraping sound that a knife makes when cutting through sand, for instance, and translate that into a series of vibrations that you can feel. It is designed to give a richer experience to music, movies, gaming and virtual reality.

When you play an acoustic instrument you get a lot of information through the skin. You feel the vibrations.

The insight on how to do this came partly from Büttner’s years of playing upright bass and his background of working at a number of Berlin-based music technology businesses. “When you play an acoustic instrument you get a lot of information through the skin. You feel the vibrations. We approach haptics like audio technology,” he says.

One of the main areas where these kinds of precise haptics are being used at the moment is games consoles, where there is a huge appetite from gamers to feel more realistic explosions, the recoil of a weapon, the wind of an enemy bullet whizzing past their face.

Lofelt provides the haptics, for example, for Razer’s collection of HyperSense gaming devices, launched earlier this year with the tagline “Feel every battle”.

Thin air

Lofelt still needs to transmit the sense of touch to users through some kind of object — a wrist rest, a mouse or even a bracelet.

But some are going one step further.

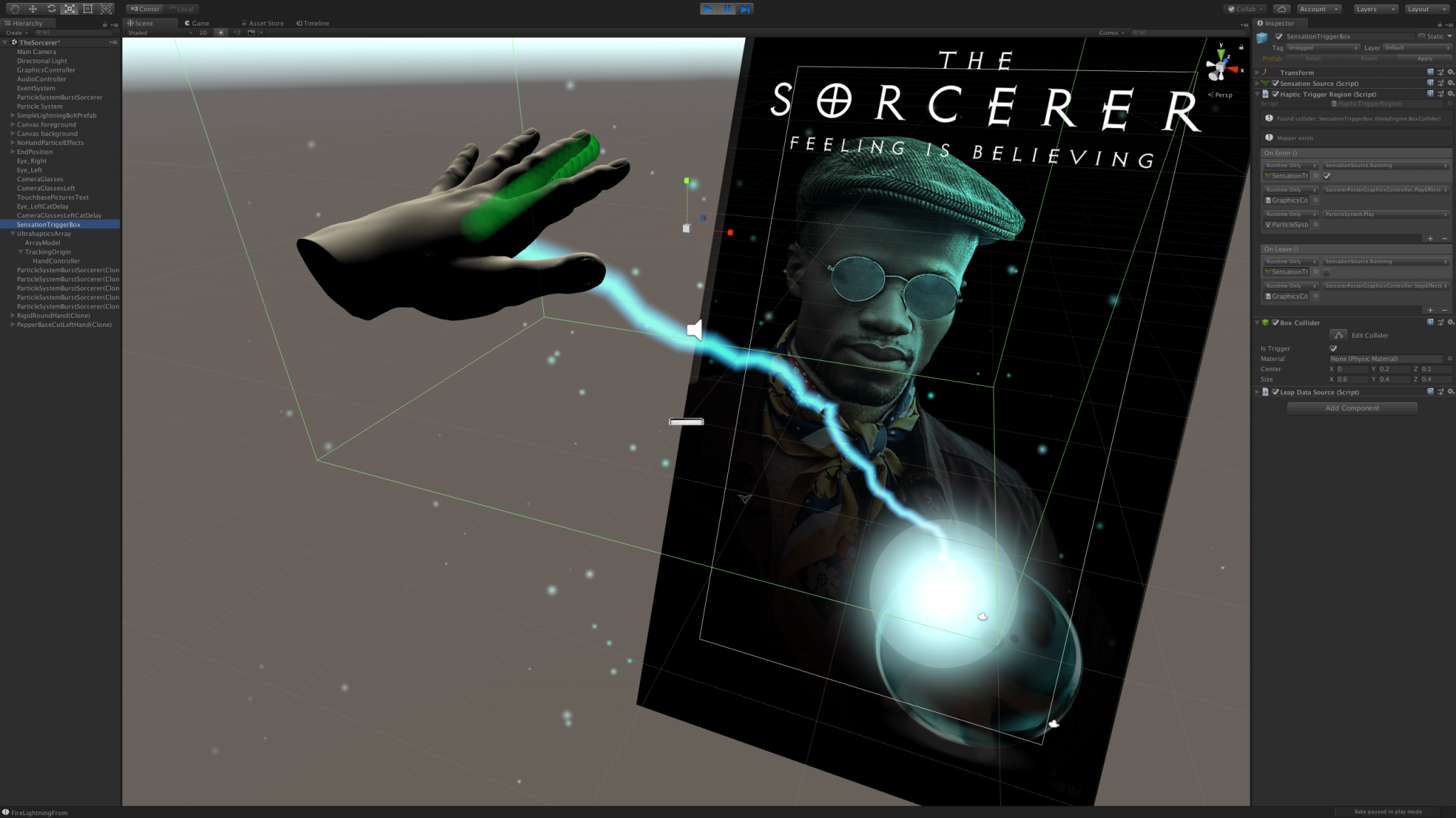

Ultrahaptics, based in Bristol in the UK, is developing so-called mid-air haptics where you can feel and manipulate “objects” that do not really exist, in thin air.

“You don’t need to wear a glove or dress up in any way. It is instant access,” says Steve Cliffe, president and chief executive of Ultrahaptics.

The sensation was a little like an underpowered hand drier but it can be ramped up to a more meaty punch.

It is done through highly concentrated sound wave (100 to 500 hertz), which cannot be heard but can be felt as pressure.

When Sifted tested it, the sensation was a little like an underpowered hand drier, although Cliffe says this can be ramped up to a much more meaty punch if needed. The company is still testing out just how hard and solid customers want their invisible objects to feel.

The technology, which was first developed as a University of Bristol PhD project by founder Tom Carter, can allow you to feel a “button” in mid-air that responds to your touch.

“Texture is a vibration. When you draw your finger across a rough surface it bounces more. We can use the frequency of vibration in the sound waves to simulate that kind of texture,” Cliffe explains.

[video width="1920" height="1080" mp4="https://sifted.eu/app/uploads/2019/02/20190130_121723.mp4"][/video]

Ultrahaptics is developing an ATM interface of the future, where a user can feel buttons in mid-air. There is a security benefit: the keyboard projection can only be seen when you stand directly in front of it, making it hard for anyone to spy personal details.

A dream for advertisers

The technology — which Ultrahaptics has been careful to protect with an array of nearly 200 patents— is starting to be used experimentally in interactive outdoor display advertising, where customers can, for example, interact with a digital poster, deflecting light sabre blows from Star Wars character Yoda with their hands.

“The advertisers love it because the attention rates they get from posters like these are hundreds of percent better than ordinary advertising,” says Cliffe. Installations of this kind of interactive advert will start to appear in the US and UK towards the end of this year, he says. The company had sales of about £2m last year, coming mainly from advertising clients.

Carmakers are the other big potential customer base. Ultrahaptics says it has been working with several large car brands, including Jaguar Land Rover and Harman, maker of audiovisual systems for cars, for several years to develop a series of gesture controls.

Drivers of the future may be able to use haptic controls to turn up the music, turn down the air conditioning or search for something on their sat nav device, simply by holding out their hand and holding up a finger or making a pinching motion with their thumb and forefinger.

Sifted found these controls fairly intuitive when we tried them at the Ultrahaptics offices in Bristol — although getting your hand in exactly the right spot for the machine to read your finger signals took a little practice.

Gesture-based controls can decrease the amount of time drivers take their eyes off the road by 25% according to a study by Ultrahaptics and the University of Nottingham.

Haptics vs. voice

An obvious and much more well-established competitor is voice — with voice-controlled assistants such as Siri and Alexa already in widespread use. Cliffe believes, however, that the two types of controls can coexist. “Certain controls work well for voice, but others work best for haptics. Telling Alexa to turn down the temperature by 1.5 degrees is more complicated than simply pinching your fingers together,” he says.

Gesture-based controls could also be a more palatable alternative to touchscreens in public places. Touchscreens in McDonald's restaurants in the UK, for example, were all found to be contaminated with faecal bacteria in a study published last year.

Ultrahaptics, which has some 120 staff, has so far raised nearly $86m, most recently a $35m Series C round in December. Cliffe says the business now plans to move from a research and development-focused stage to serious commercial engagement, starting this year. The next two years will be a crunch time to see if the technology really can go mainstream.

Lofelt is a smaller operation of 20 staff and just $6.7m in funding raised to date. It is opting to focus primarily on gaming, where Büttner says he is most confident of growing demand.

It's a bit like colour television. You’d never go back to watching TV in black and white.

“Haptics used to be an afterthought when games companies developed a new console. They might spend just a week’s development time on that part. Now it is becoming more of a priority and being thought of right at the start of development,” he says.

A high-quality touch experience, Büttner adds, will soon become something consumers expect from their devices.

“Once you have more realistic haptics, it's a bit like colour television. You’d never go back to watching TV in black and white.”