Voters in the east German states of Saxony and Thuringia will be heading to the polls on Sunday to elect new state governments — and some startups are concerned about the prospect of Germany’s far right party Alternative Für Deutschland (AfD) gaining even more influence.

According to opinion polls, the AfD is on track to come first place in Thuringia where it is polling at about 30%; in Saxony, pollsters predict a tight race between the AfD and the centre-right Christian Democrats (CDU). The AfD will also take part in elections in Brandenburg on September 22.

Analysts say the AfD’s chances of securing a majority are slim, meaning it would need to get the support of another party to form a coalition or minority government. But all other parties are currently refusing to work with it.

Nevertheless, the elections could give further legitimacy and decision-making power to the party on a state level, and impact national politics.

“I'm sure that if the AfD should get over 30% on Sunday, we have a huge problem over here,” says Christiane Kilian, chairperson of STIFT, a foundation for technology, innovation and research in Erfurt, Thuringia.

Startups fear that rising influence of the far right could impact the region’s ability to attract talent and investment from outside, and see high-growth tech companies slip down the political agenda.

Sifted reached out to the AfD for comment on this story, but did not receive a response before publication.

Who are the AfD?

The AfD is classified as a suspected right-wing extremist organisation by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution; the party lost an appeal it made against this label in May this year. In some states, like Saxony and Thuringia, the party is “confirmed right wing extremist”.

In its election manifesto, the AfD has made clear its desire to abolish the Euro, limit immigration and battle against EU climate policies. Gender diversity is stated in the manifesto as a social construct that “denies the natural gender polarity” of man and woman and “leads to the destruction of the family”. Meanwhile, the AfD wants to offer subsidies to families with newborns to increase dwindling birth rates.

The AfD’s political agenda hasn’t found much support among German startups at a national level, data shows. An excerpt from the upcoming German Startup Monitor 2024 reveals that 41.3% of German founders surveyed said the Green Party is their favourite; less than 5% of founders selected the AfD as their first choice.

“Populist answers fail with startups,” says Christoph Stresing, managing director of the German Startup Association in a statement. “Real innovation needs openness.”

Concerns over hiring talent

One big concern among founders in the eastern states is that increased AfD influence will make hiring international workers, especially those with highly coveted skillsets in engineering or IT, even harder.

Startups from eastern Germany rated their ability to attract international talent as significantly below average in the 2023 German Startup Monitor — and some think that the AfD’s hostile approach to immigration could make things a lot worse.

Our success as a deeptech startup is dependent on finding international talent in the specialisations and skill sets we need.

“How would you [as an international person] feel moving to a state where a political party is active that’s very offensively raging against foreigners?,” says Christian Piechnick, whose deeptech startup Wandelbots employs 120 people from 25 nationalities.

“Our success as a deeptech startup is dependent on finding international talent in the specialisations and skill sets we need. Typically, [these] are not easy to find, and needless to say, it’s not necessarily Germans taking these jobs.”

Ede Möser, coordinator for the international startup office at the International Startup Campus in Jena, Thuringia's second largest city, is observing a trend of young companies wanting to move to cities like Berlin, Hamburg or Munich where hiring international talent is easier.

He adds that Thuringia’s research capacity and the development of its deeptech startups is dependent on talent from overseas. In Jena, 4,402 jobs were created between 2019 and 2023, including 2,920 tech jobs; 42% of the total jobs were filled by international candidates, according to data from the Employment and Economic Development Agency in Jena.

Aside from the tech industry, migration is needed to make up worker shortages in important areas like healthcare and education and “keep society functioning” as one entrepreneur from Pirna, a town in Saxony, who asked to remain anonymous, put it. By 2035, Germany’s ageing society will be lacking 7m skilled workers, a hole that analysts say can only be filled with migration.

“Germany’s economic strength is inextricably linked to the diversity of its population. Immigrants and foreign-born individuals have been vital contributors to the economy as taxpayers, healthcare professionals and company leaders,” says Ana Alvarez, founder and CEO of Migrapreneur, an organisation helping migrant founders set up businesses in Germany.

“It would be risky for German politicians and company leaders to not tackle the anti-foreigner sentiment, as the country’s economy cannot afford any setbacks during this period of rapid demographic change.”

“Lost in the 1930s”

Many founders in the east are concerned that tech startups are not on the AfD’s agenda.

The party hints in its manifesto that it wants to support SMEs in crafts, services and manufacturing, reduce bureaucracy and make it easier for people to start companies. But there’s no mention of supporting the growth of the tech industry that many see as key to the future competitiveness of the German economy.

“The AfD are not very tech-focused or future-focused and startups are afraid the party will not be supportive to the ecosystem,” says Hans Elstner, founder and CEO of rooom, an enterprise metaverse solution based in Jena.

“They’re also afraid that the AfD doesn’t have any idea or plan to [offer] funding programmes. And, they’re afraid that investors from all over the world, even from Munich, will not tend to invest into companies in the east of Germany.”

STIFT's Kilian agrees: “The AfD is not a business friendly party. How can you support startups when you are lost in the thoughts of the 1930s and 40s?” she says.

Founders in Thuringia and Saxony say that Germany’s history — which saw the east of the country isolated under Soviet rule until 1989 — has meant that there hasn’t been as much investment in their part of the country as there has been in the west, and that it is far less affluent. Wages in the east are 20% lower for the same job than those in the west, according to research from 2DF’s investigative documentary series Frontal.

The most well-known startups in east Germany include Wandelbots; employee communications platform Staffbase, which has 765 employees; and Sunfire, which offers renewable hydrogen and Syngas and has over 650 employees.

And while there are many promising deeptech startups coming out of universities and research institutions, states like Saxony need much larger, “homegrown” companies for the ecosystem to grow, says Piechnick. Ideally, employees would earn “a lot of money” in tech companies in Saxony and then use it to invest in startups in the local ecosystem, or found one of their own. He points to German heiress Susanne Klatten who inherited shares in BMW which she channelled into building up the local business ecosystem in Munich.

“This [process] will not happen in an AfD-run country. I think the opposite will happen,” says Piechnick. “People will move away, they won’t spend their money here and will use it somewhere else. I think that’s the biggest threat.”

Startups rising up

For many people in the east of Germany, the future of the tech ecosystem relies on maintaining a culture of openness, tolerance and democracy — values that some believe the AfD does not share.

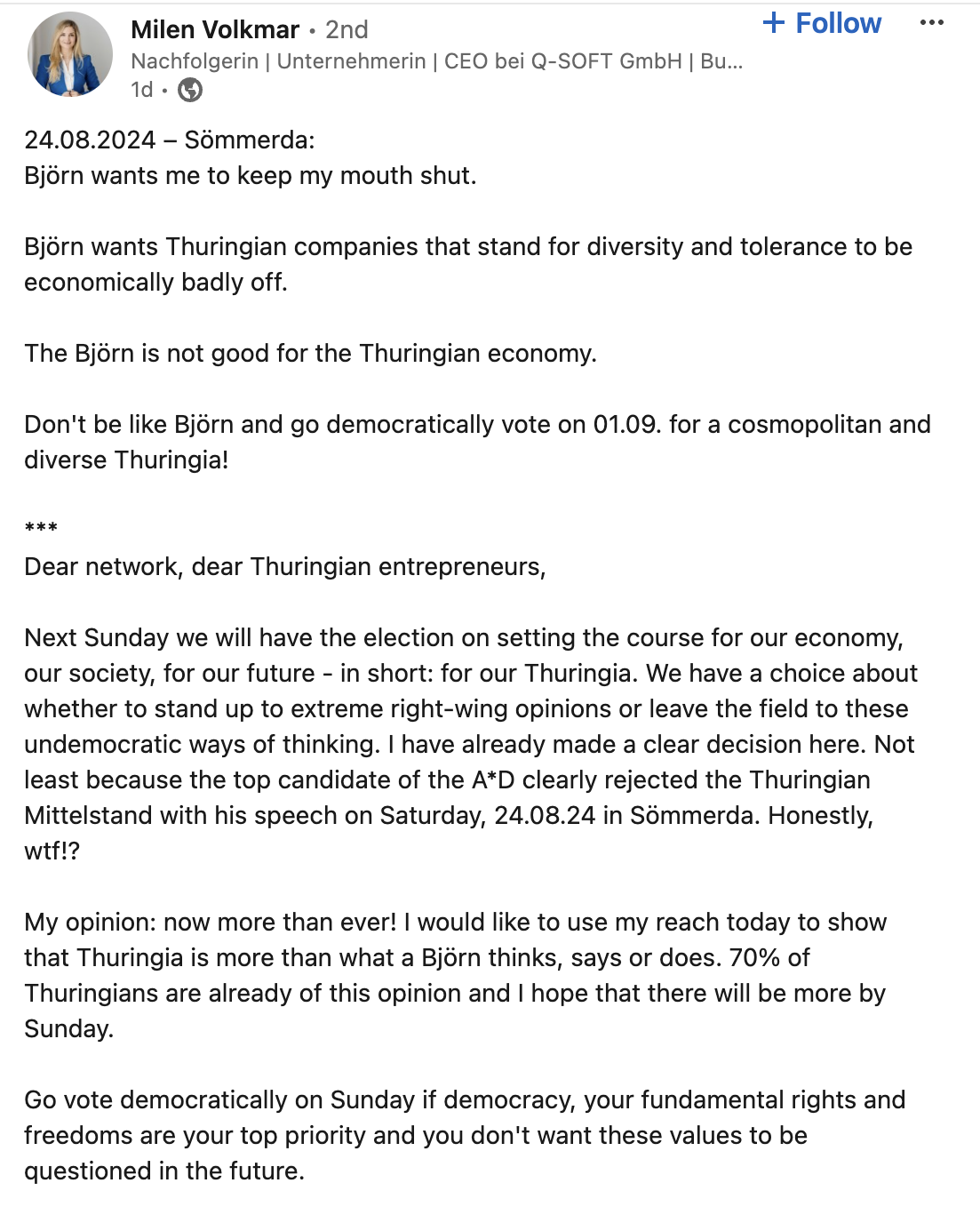

This bubbled to the surface this week when Thuringian AfD leader Björn Hocke commented on a campaign dubbed “Made in Germany — Made by Diversity”, organised by 40 German family businesses to celebrate diversity in society.

The politician said of the companies involved: “I hope these companies will experience serious, serious economic turbulence,” prompting a backlash in the German media.

Kilian says founders were “shaken” by these comments and are now even more motivated to stand up against the party, with some now speaking out publicly on social media.

“I was born here in 1980 so I lived in a dictatorship before I had the opportunity to live in a country that made it possible to travel, to make this career and to support startups and innovation,” says Kilian.

“That’s why it’s so important to say that innovation does not stop at national borders and that’s why we need an open-minded society. It’s so important to tell people, you are welcome here. We need you for our future,” she adds.

In Thuringia, counter initiatives have been formed to fight for an open and diverse society that celebrates difference: such as “Cosmopolitan Thuringia” — an alliance of over 8k businesses, organisations such as football clubs and research institutions and private individuals. Jenoptik, a large optical tech company in Jena, has its own campaign called “Stay Open”.

These initiatives are important, says Möser, to ensure the city of Jena and the broader state of Thuringia are still perceived as attractive locations for young and international people to live and work.

Founders in Saxony and Thuringia hope that even if the AfD does win the election, entrepreneurs will stay in east Germany and that investors will continue to invest in the region’s talented startups.

“It’s a great opportunity for investors to support the great people over here, because we are not a failed state,” says Killian. “We are a region that’s on the edge right now, but it’s so important to stand with us, support us.”