For any founder, negotiating fair deal terms with an investor is key. Signing an unfavourable term sheet — the document that governs the terms of the deal — can, after all, be the beginning of the end.

With more VC money than ever available to European founders, the cards are increasingly stacked in founders’ favour when negotiating. But how can founders really know what to expect?

In order to give founders a peek into what terms frequently look like, advisory firm Mountside Ventures analysed term sheets from 203 VCs, venture capital trusts (VCT), CVCs, family offices and angel groups across Europe.

It’s the first analysis of its kind, according to the company, although there have been reports by professional services and law firms on how term sheets on deals they’ve been involved in stack up.

The report comes amid growing calls in European tech for greater transparency in VC — from the investors themselves to the founders they back — and in 2020 the ecosystem’s first anonymous VC review platform launched, pegging itself as the “Glassdoor for venture capital”.

Founders take note — from fees to vesting and share preferences to board seats — here’s what you can expect to see in a term sheet.

Scroll to the bottom to see a breakdown of the "market" term sheet.

1/ Fees

It’s likely you’ll be lumped with some fees from investors, and these tend to fall in two camps: deal fees, like legal and due diligence costs, and management fees, which are the admin costs of the day-to-day running of a fund and change depending on the type of organisation you’re raising from.

70% of funds analysed recharged the legal and diligence fees associated with doing a deal to the companies they invested in.

VCs don't charge management fees to the companies they invest in. Instead, these fees are taken from those investing in the VC themselves: the limited partners. Over the lifetime of a fund, those can add up to 15% of the fund size.

Angel networks, on the other hand, do tend to charge the companies they invest in management fees, and these typically fall between 5% and 10% of the investment received. Because angels often help bring in other angels to a deal, it’s a bit of a “finder's fee”.

Although management fees tend to be smaller when raising venture debt — between 1% and 3% — these organisations charge interest of up to 15% over a three to five year period. Founders who go down the route of venture debt, however, don’t have to give away ownership in their company in exchange for this capital.

2/ Founder vesting

You’ll probably have to commit to vesting — which means agreeing to a certain amount of time before shares become yours. Just 2% of investors didn’t ask for founder vesting, and it’s so common because from an investors’ point of view it's supposed to ensure a founder’s long-term buy-in.

The most common scenario was for shares to vest over four years with a 12-month cliff — meaning a portion of shares become yours at the end of the first year after investment, and then steadily increase over the remaining three years.

3/ Share preference

80% of investors want preference shares, granting them special privileges over those with ordinary shares — like the founding team or early employees.

Preference shares can mean a number of things, but most commonly in VC, they mean in the case of liquidation, the investors get their money back before others do.

The report also says that it’s common for investors to look to protect against a down round with an anti-dilution clause. But founders beware: this can be a slippery slope to losing a whole lot of equity the next time you come to fundraise.

4/ Board seats

Typically, you’ll be expected to give up a seat on your board to an investor, and this is most common at Series A. Two thirds of angels, accelerators and incubators also ask for a board seat, and funds that lead deals nearly always do.

But, there have been calls in the past from investors for VCs to hand over their board seats to qualified directors that bring more practical nouse and can diversify the board.

5/ Exclusivity periods

Most investors want some period of exclusivity. 35% required four weeks — which was the most common term — although interestingly, 26% did not require any exclusivity period.

But, the report points out that the majority of these were co-investors, which would rely on the lead investor to negotiate an exclusivity period.

Other things to look out for…

- ESG clauses. 67 of the 203 investors told Mountside they included an ESG clause.

- Personal guarantees. 31% of investors have used personal guarantees at least once in the past — which make the founder liable for losses.

- Right of first refusal. 66% of investors have included the right to buy any shares from anyone selling before anyone else can.

How long does a deal take to complete?

The report also looked at how long it takes to get a deal over the line, measured from the first meeting with an investor to cash hitting the company’s bank account.

50% of investors said that it took them between eight and 12 weeks to complete the due diligence and finalise equity documents, but there are a number of steps the report says founders can take to shorten the deal timeline:

- Have all the necessary information to upload to the data room

- Ready responses to the most common FAQs that investors raise

- Negotiate in as much detail as possible at the term sheet stage, as this will mean it’s quicker for lawyers to prepare the equity documents.

Another route to a speedy deal is getting backing from a solo capitalist. These “lone wolf VCs” have gained prominence in the US in recent times and are now emerging on the European tech scene, with a reputation for pace and agility.

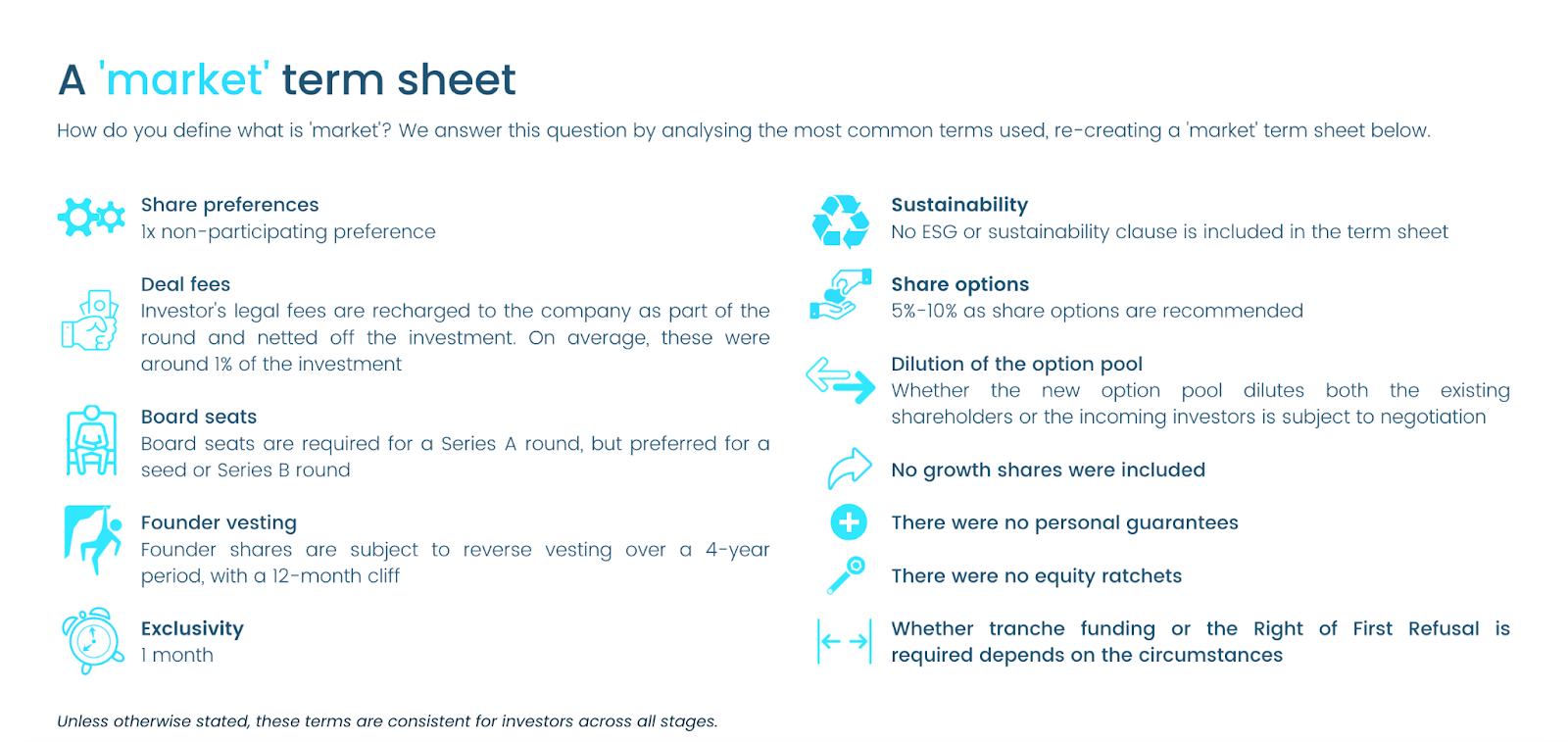

The ‘market’ term sheet