Last week Lilium announced that it would list on Nasdaq via a reverse merger valuing the German flying taxi company at $3.3bn — the latest in what is starting to look like a SPAC stampede in the urban air mobility sector.

In February, California-based Joby, considered to be the leading company in this space, announced a deal with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) that would value it at $6.6bn; while Archer Aviation, also based in California, announced a SPAC deal that gave it a $3.8bn valuation.

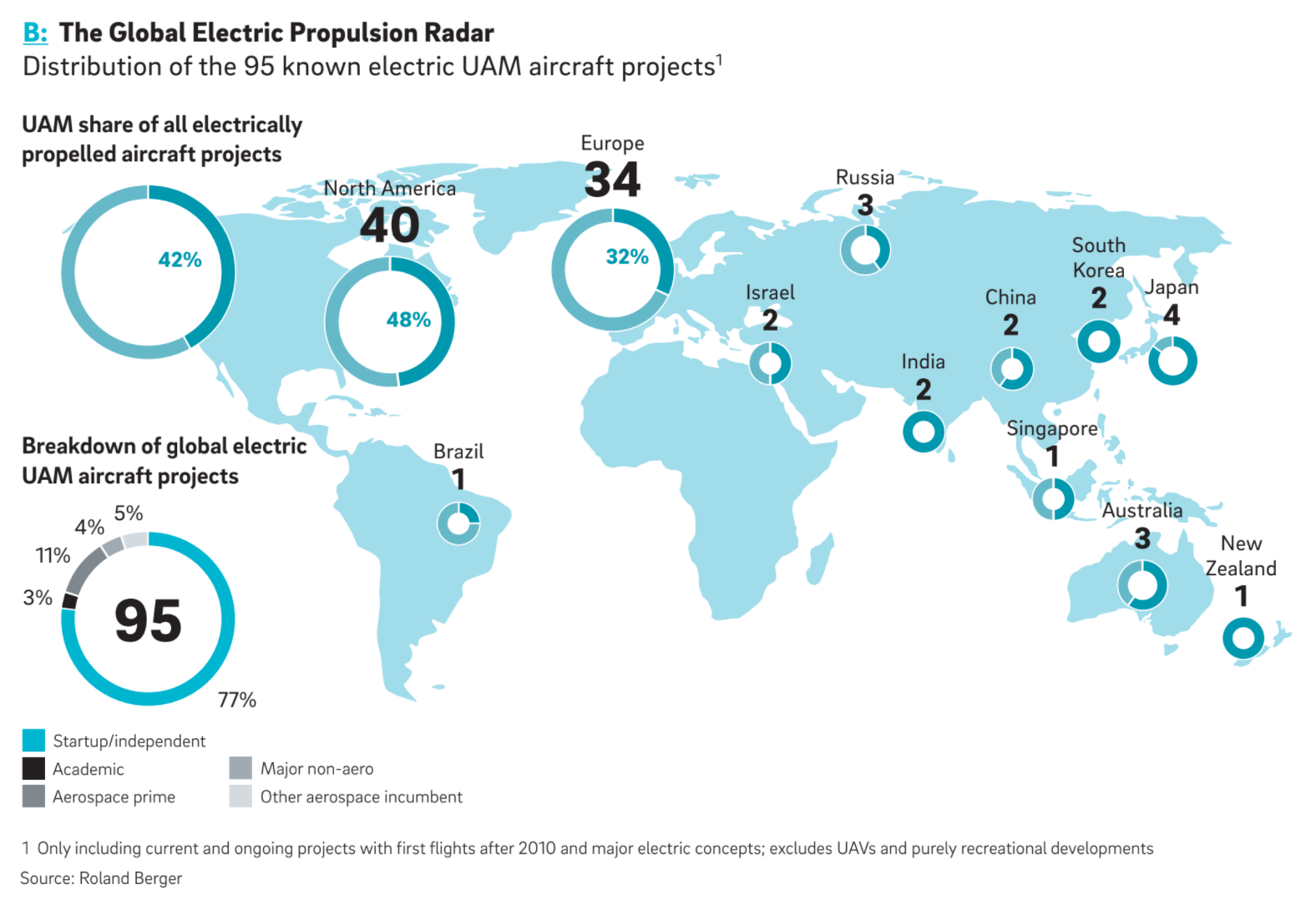

There are some 95 projects around the world developing electric passenger drones, and a growing number have $1bn+ ‘unicorn’ valuations.

Germany’s Volocopter hasn’t gone for the SPAC route, instead raising a €200m Series D round in March. Meanwhile China’s EHang, which has been listed on Nasdaq since 2019, saw its shares rise sharply in February, and even though they have come back down again in March it still has a market valuation of $1.85bn.

“We have entered into this with our eyes open, but we are very excited about the size of the market,” Barry Engle, founder and CEO of Qell Acquisition Corp, the SPAC which announced the merger with Lilium last week, told Sifted.

There’s a gold rush feeling in the industry — but not everyone will get rich, that’s for sure.

Investors are piling in as many of these projects start serious negotiations to get certification from aviation regulators and many are promising to start services by 2025 — some even as early as 2023. But are they set to be disappointed?

“There’s a gold rush feeling in the industry — but not everyone will get rich, that’s for sure,” says Manfred Hader, who heads the global aerospace and defence practice at consultancy Roland Berger.

Predictions about the size of the market vary considerably. Volocopter believes urban aviation has the potential to be a €240bn market by 2035 — half of that from passenger transport, half from cargo services — while Roland Berger expects the sector to generate a far more modest $1bn in revenues by 2030, growing to more than $90bn by 2050.

To keep this in perspective, the global taxi market is expected to be worth around $300bn by 2030. Volocopter’s projections would see flying taxis take a big share of it — Roland Berger’s a much smaller part.

Can we believe the timing?

Size of the market aside, one of the biggest questions at the moment is whether urban aviation companies can really meet the very aggressive forecasts for launching services. Volocopter has promised to launch commercial services within two years — that would be by 2023. Joby, Lilium and Archer have all set 2024 as the date for starting commercial services.

But although flying taxi companies are talking about similar start dates, there is a big difference in the number of test flights they have flown. Joby (founded in 2009) and Volocopter (founded 2011) have each flown more than 1k test flights.

But Archer has yet to release a photo of its full-sized aircraft or any footage of it going from vertical take-off to flight. Lilium, meanwhile, has had a year’s hiatus on test flights, after its five-seater prototype aircraft was destroyed in an electrical fire last spring. Test flights will not resume again until later this spring, the company said, and the new seven-seater aircraft with which Lilium is planning to launch commercial services won’t start testing until 2022.

Plus, last autumn, the company saw a number of senior hires leave the company including the VP of digital technology and VP of infrastructure, with insiders telling Sifted that there was a sense of frustration as projects had failed to progress as fast as they had expected, echoing a detailed story in Forbes on this same subject.

Startups live by good news, and so they may say 2025. But incumbent aircraft companies have said not until the end of the 2020s.

All this makes the timing for getting a commercial service in operation by 2025 feel very tight. But Engle told Sifted he was very confident about Lilium meeting the timing it has set out.

“There is a significant financial implication if we are wrong on the timing. But we did extensive due diligence for five months and were able to get very comfortable with what needs to happen. The team has made huge progress,” he said.

He said outside experts brought in by Qell to evaluate Lilium ahead of the deal had confirmed they expect the company to receive certification from aviation authorities by mid-2024.

“We built the business plan around that,” he told Sifted.

However Hader still has some doubts.

“Startups live by good news, and so they may say 2025 or earlier [for launch],” he observes. “But incumbent aircraft companies have said not until the end of the 2020s.” Hyundai, for example, has said it plans to launch an air taxi by 2028.

Missing a launch deadline, however, is not a serious problem, he says. “Whatever happens between 2025 and 2030, we won’t see much volume. The real scaling up will happen after that.”

Can we believe the technology?

There are many urban aviation projects that already regularly fly, for example from EHang and Volocopter, so we know that at least some of this technology really works.

But the ones that are flying at the moment are pretty much all of a certain type — quadcopters and multicopters that look like bigger-souped-up versions of recreational drones.

They are two-seater aircraft and are mainly suitable for short flights within a city, distances of no less than 50km and flights lasting no more than 20 minutes or so. Volocopter’s range, for example, is around 35-65km, and its cruising speed is around 90km per hour.

We have the technology to fly 50kms. Whether we will be able to fly five people for 300km is a very valid question.

“We have the technology to fly 50kms,” says Hader from Roland Berger.

There is a bigger question, however, about the viability of some of the other more ambitious projects which are promising a more radical transformation of global transport. “Whether we will be able to fly five people for 300km is a very valid question,” says Hader. “The companies are keeping their cards very close to their chest. It is hard to know if they are bluffing or if they already have the breakthrough.”

Joby, for example, is promising a range of 240km for its five-seater tilt-rotor plane, and Lilium says it will be able to fly its seven-seater jet 250km on a single battery charge — something that many aviation engineers still question.

Some sceptics doubt that the current generation of lithium-ion batteries — which have an energy density of between 100 and 265 watt-hours per kilogram — would provide enough energy for long, intercity flights.

Daniel Wiegand, cofounder and CEO of Lilium, says that is a misconception, and that Lilium will be able to deliver the range it promises with currently available batteries. He says Lilium’s ability doesn’t depend on some new, unknown battery technology being discovered.

There is no big battery secret.

“There is no big battery secret,” he told Sifted. The company is using lithium-ion batteries with higher amounts of silicon in the anodes, which does increase battery capacity by a small percentage. But this is nothing secret or experimental — Tesla has also been moving to using batteries like these in its cars.

Lilium says the unique design of its aircraft, with rigid wings that create lift while cruising, help minimise energy consumption, allowing it that longer range. However, aviation engineers point out that Lilium’s aircraft will need to work even harder than other types of electric aircraft to rise vertically in the first place.

Better batteries

New batteries, based on different chemistries, may help the flying taxi operators in due course. Wiegand told Sifted Lilium engineers were looking at these, although not for immediate use.

He didn’t name specific companies but Nyobolt, a Cambridge-based startup, for example, is developing an ultrafast niobium battery that can deliver a much more powerful ‘kick’ of energy, useful for electric aircraft taking off vertically. Sai Shivareddy, Nyobolt cofounder and chief executive told Sifted the team was in talks with a number of electric aviation companies.

Similarly, sodium-ion batteries, such as those being developed by OXIS and Zenlab may be able to provide much higher energy densities than lithium-ion batteries. The problem is that these batteries are still several years away from being commercially available — OXIS, for example, has said its solution will not be ready for use in aircraft for three to five years. They are also likely to be much more expensive than standard lithium-ion batteries.

We don’t believe the tech will be a showstopper.

Still, Hader says that the technology is unlikely to be — at least in the long term — the biggest stumbling block for the industry.

“We don’t believe the tech will be a showstopper. For long hops, we don’t have the technology, but it is a matter of time until we do — if it is not for 2025, it could be for 2030.”

Public acceptance

Getting regulatory certification for a new commercial aircraft takes around six years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars, but this is not expected to be the biggest problem for urban electric aircraft.

Companies like Lilium are already some way down this process. Last year, Lilium received CRI-A01 certification basis from the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) for the seven-seater jet, meaning that they have a clear understanding of the requirements they will have to meet for certification — although there is still a long road to actual certification itself. Volocopter is expecting certification from EASA by 2022 and Joby Aviation is working towards certification from the US Federal Aviation Administration by 2023.

But in addition to official certification, flying taxis will also need to get public acceptance. And this, says Hader, is much more of an unknown.

Would you, would your grandmother, be willing to fly in one of these vehicles?

“Would you, would your grandmother be willing to fly in one of these vehicles? Before we can know that for sure we need to get something in the air and get people used to it. We need demonstrations. Before that, you can forget any market projections,” he says.

Very visible public demonstrations — such as Volocopter’s plans to operate services during the Paris Olympic Games in 2024 — will be a key part of getting people used to the idea of flying taxis.

“The Paris games will be a milestone because everyone will be there, the media, all the influencers," says Frederic Aguettant, founder of Helipass, the booking platform for helicopter and urban air mobility flights.

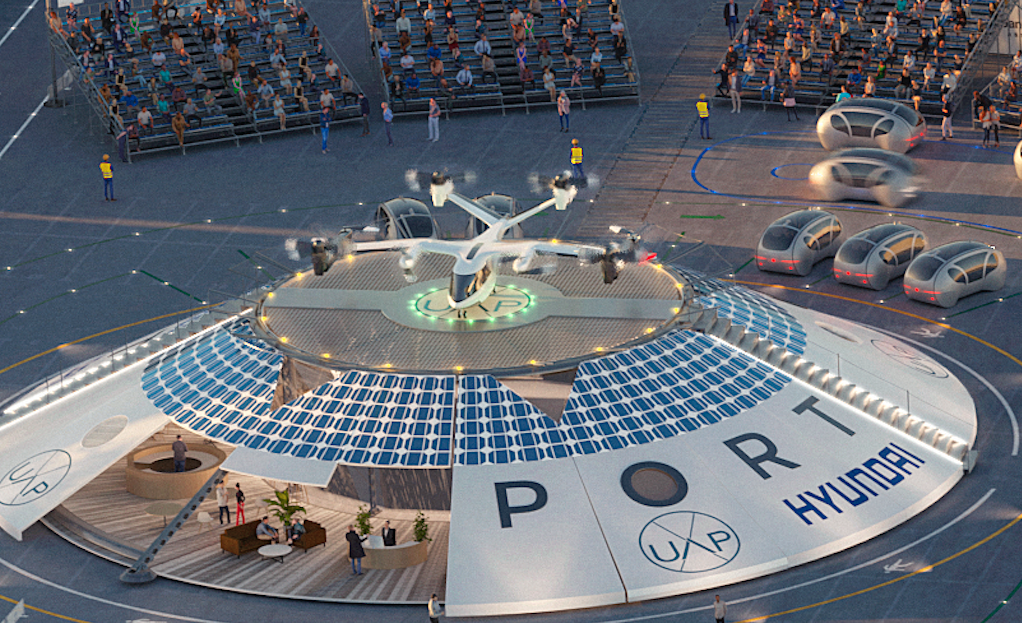

Similarly, Urban Air Ports is building a UAM hub in Coventry in the UK as part of Coventry’s ‘City of Culture' celebrations in 2021. The air hub will have little traffic initially — perhaps a few delivery drones — but Urban Air Ports founder Ricky Sandhu said it was important for getting people used to having hubs like these in their cities. It may sound mundane, but the most crucial part of the design may be the café, which will help draw in a wide variety of people and help to make the air hub seem normal.