It's difficult to get excited about startups you can't see.

Yet major investors are betting that it's precisely the fintechs you don't know – the backend operators, that sit behind your pre-paid cards and lending apps – that will become profitable, billion-dollar companies in the next five years, according to a new report.

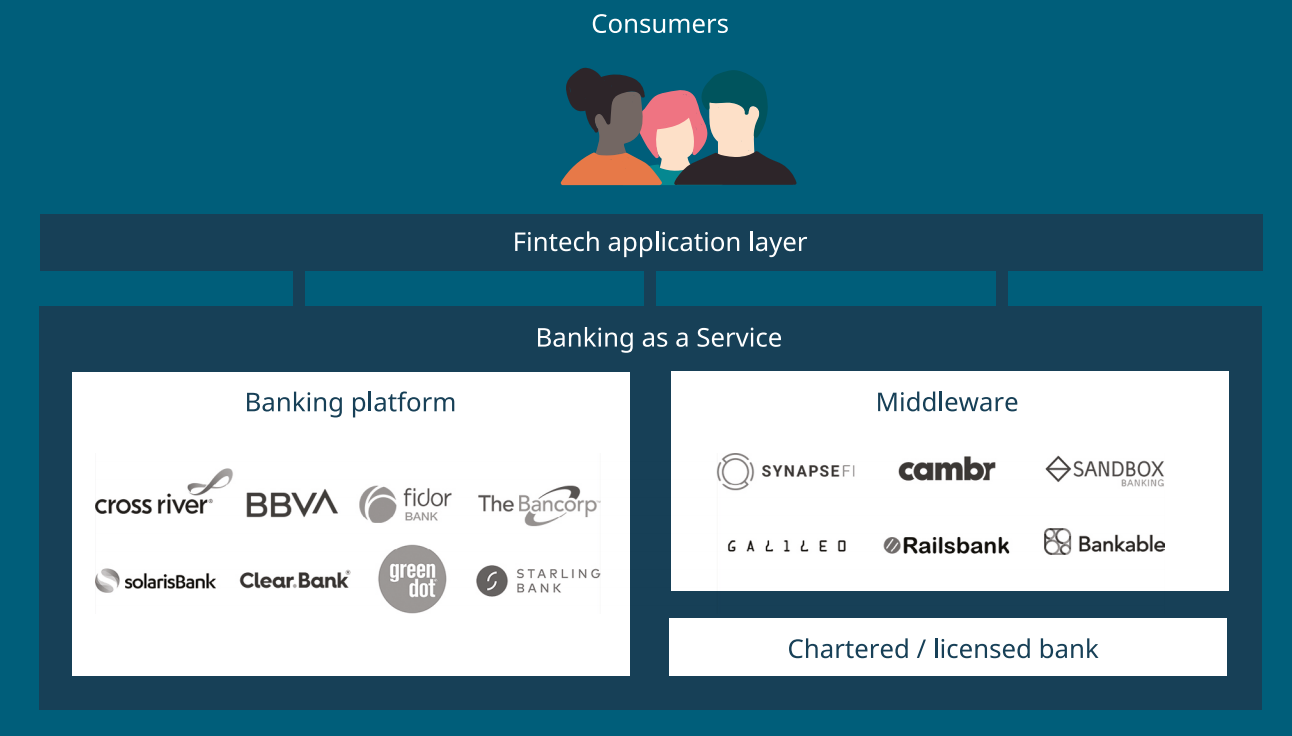

So-called 'fintech enablers' (or 'banking as a service' players) are the technology platforms that quietly rent out their core banking infrastructure to power countless financial apps and services.

Examples of this small pool of infrastructure-focused fintechs are outlined in the graphic below. These include Germany's Solaris Bank, which last week closed a €60m Series C in difficult fundraising conditions, and the UK's ClearBank, which powers four million “user accounts” via its fintech clients — almost as many as Monzo.

To date, enablers have helped countless fintechs like Tide and Spendesk come to market faster by providing them with core chunks of the banking technology ‘stack’, such as compliance, authentication and payment processing.

A reliable revenue model has emerged from this, as consumer fintechs generally stick to their chosen banking platforms for a long time (it is complex and expensive to migrate).

An IPO is on the table for sure

Yet the real value VCs see in them is that by modularising banking, fintech enablers can help companies of any genre — from Uber to Amazon — to offer financial services; a hugely lucrative and vast field.

"Almost every startup will partake in the financial world — and therefore need [enablers] to manage their ledgers, accounts, cards etc," says Simon Schmincke, a partner at Germany's Creandum. "The demand for providers which lend their financial licences to others is increasing rapidly."

Investors' long-term thesis is that enablers will help blur the lines between tech companies and financial services, and then provide big tech with the desired current accounts and payment rails. This leads to strong unit economics, a large total addressable market, and the ability to create "trillions in value," says EQT Ventures partner Tom Mendoza.

"The winners in BaaS are strong IPO candidates and will have ample M&A suitors," Mendoza adds.

Indeed, enablers have already shown they have strong exit potential. Galileo (a US-based enabler) was bought for over $1bn earlier this year by SoFi, a major lender. Meanwhile, in 2018, Societe Generale bought France’s Treezor, which provides white label banking services — suggesting big banks are also sniffing out the area.

Billion-dollar IPOs?

None of Europe's enablers have earned the coveted title of a 'unicorn' startup yet.

But Nicolas Brand, a partner at European VC Lakestar and investor in Solaris Bank, says it's a matter of time before one of them hits a billion-dollar valuation.

In particular, Solaris Bank was valued at $360m in its most recent fundraise, and its new investors "will be expecting venture-style returns [of 3x or more]," Brand highlights.

"There's clear ambition for Solaris [Bank] to become a unicorn."

But it's not just surging valuations that have caught investors' eye; it's also this group of fintechs' proven ability to monetise that has stood out. The biggest players have turned over tens of millions in revenue, according to sources with direct knowledge of the companies —even prompting long-term ambitions about going public.

"The idea that these players get to significant size and profitability is not too crazy: They provide valuable, sustainable, high margin services. And those are well thought after at public markets," says Creandum's Simon Schmincke, hinting at the possibility of a future IPO for the bigger breed of enablers.

Brand also confirmed that an IPO "is on the table for sure" for Solaris Bank, adding that €100m in revenue was generally a good benchmark for going public.

It's worth noting that going public carries its own challenges and high-level scrutiny, leading one commentator to call the idea of BaaS players going public "insane".

Nonetheless, Barbod Namini, an investor at VC firm HV Holtzbrinck Ventures, explains enablers with bank licences may have little other alternative.

“If you’re a fully licensed bank, your routes to exit are very limited. It’s an absolute nightmare to be regulated as a bank. So their choices are an IPO or, if they’re not big enough but profitable, it’s private equity."

He added that being bought by a traditional bank could also damage BaaS' independence and ability to service a broad set of customers.

Early days

For all the space's utility and potential, it's worth flagging it's still in its early stages — or the first "wave". As a result, we are likely to see as many casualties as there are meteoric successes.

We may also have a while to wait before some key players reach IPO or exit viability. For instance, ClearBank only launched in 2017, recording just £850k in revenue in 2018, according to Companies House.

Finally, the Wirecard saga has shaken fintechs' confidence in third parties like BaaS providers, says fintech consultant Lars Markull.

"The more control, the better," Markull told Sifted. "Pre-Wirecard, startups preferred to invest their resources into more product-related projects. Now it might be more focused on controlling more of the supply chain."

On the flip side, many BaaS players have stepped in to fill the void left by the demise of Wirecard and its UK subsidiary, which should help them in the short-term. But if self-sufficiency is favoured over speed, it could seriously impact fintech enablers' prospects.

UK regulators are also expected to apply stricter guidelines to third-parties, which could impact BaaS players' ability to scale at speed.

***

To read more about enablers and their role, check out our Fintech Unwrapped report. Download it here.