These days you can print everything from human tissue and vegan steaks to industrial parts and a pair of jeans.

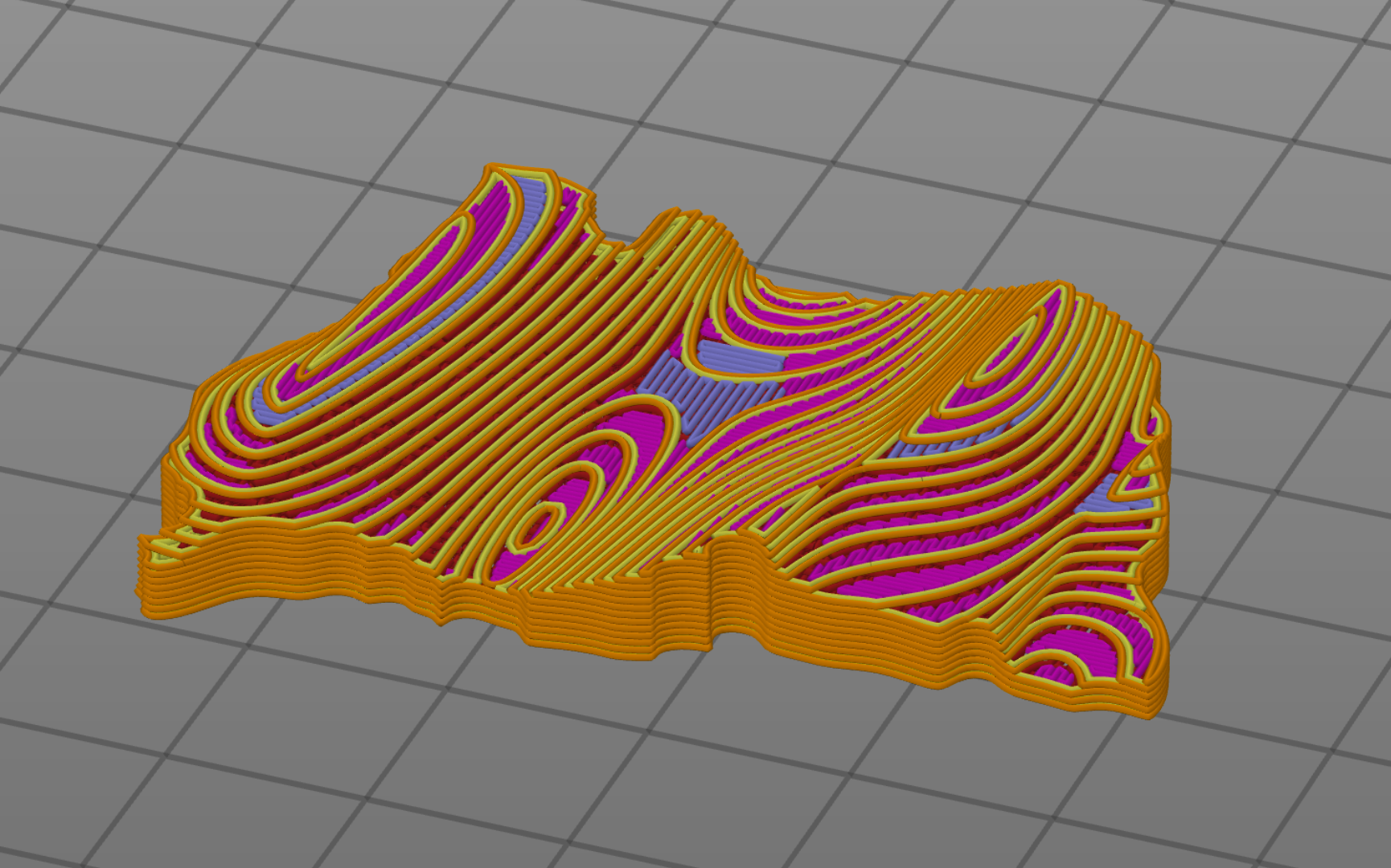

While the technology is not yet quite at the level of the Star Trek replicator machine, there is a thriving European tech ecosystem edging us in that direction.

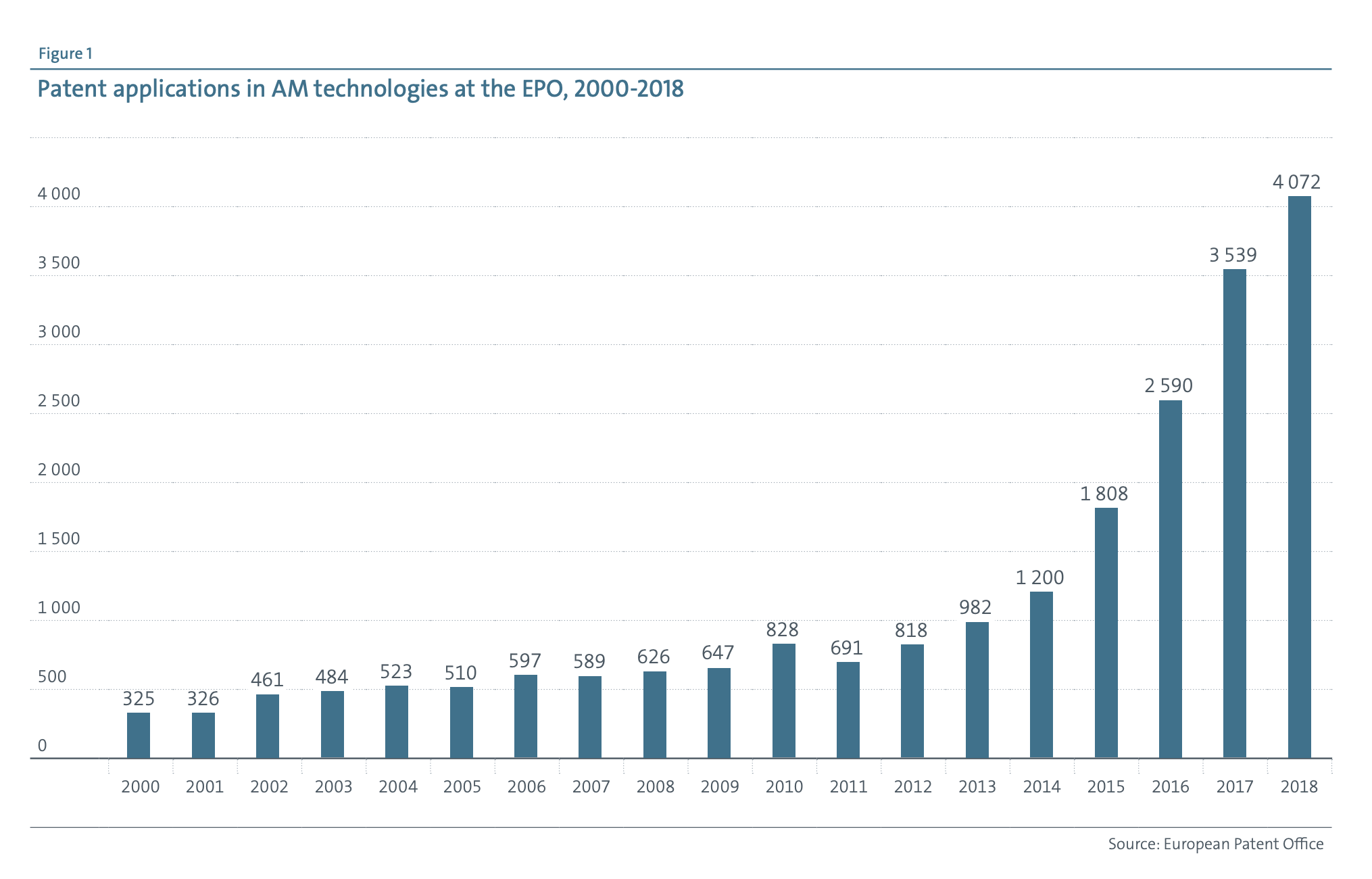

This can be seen in the European patent applications related to 3D printing, which has been growing at a rate of 36% a year according to the latest data from the European Patent Office.

The data shows the intense excitement about 3D printing. While the majority of 3D printing is still focused on business-to-business uses in manufacturing and industry, there is a growing use of it for consumer applications as well.

“There’s growth in companies that are using it for very specific purposes,” says Benjamin Joffe, Partner at SOSV, a global VC fund focused on early-stage deep tech startups and investing in over 100 startups per year.

SOSV was an early investor in 3D printer-maker Formlabs, but has recently been branching out into investing in more niche applications of the technology, such as Kniterate, which makes knitting machines that borrow from 3D printing techniques, and Unspun, which uses 3D body scanners to create made-to-measure jeans for customers.

“3D printing was overhyped for years, especially between 2008 and 2014, but now it is really starting to deliver on its promises. It has always had strong B2B uses, replacing industrial processes like injection moulding. But now it is also finding consumer uses in mass bespoke manufacturing,” says Joffe.

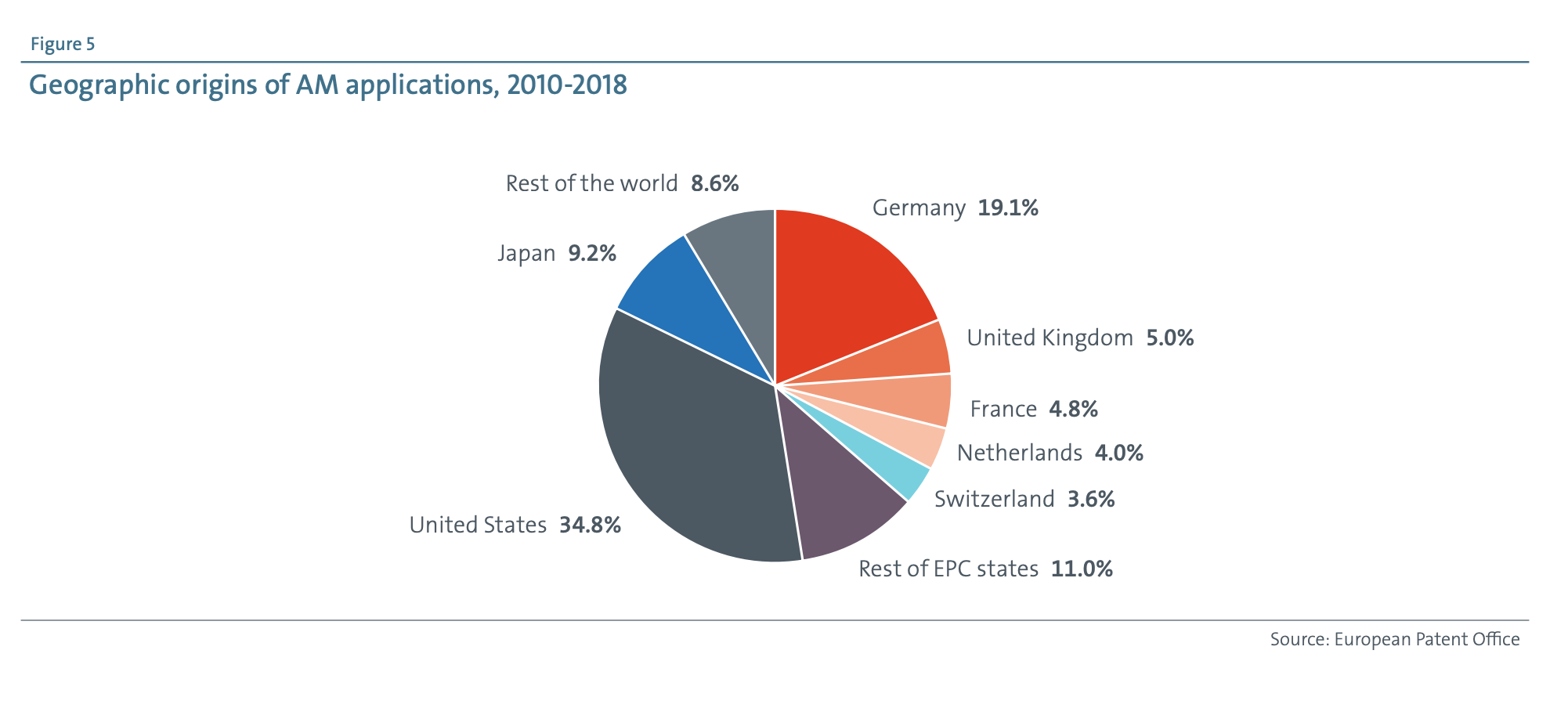

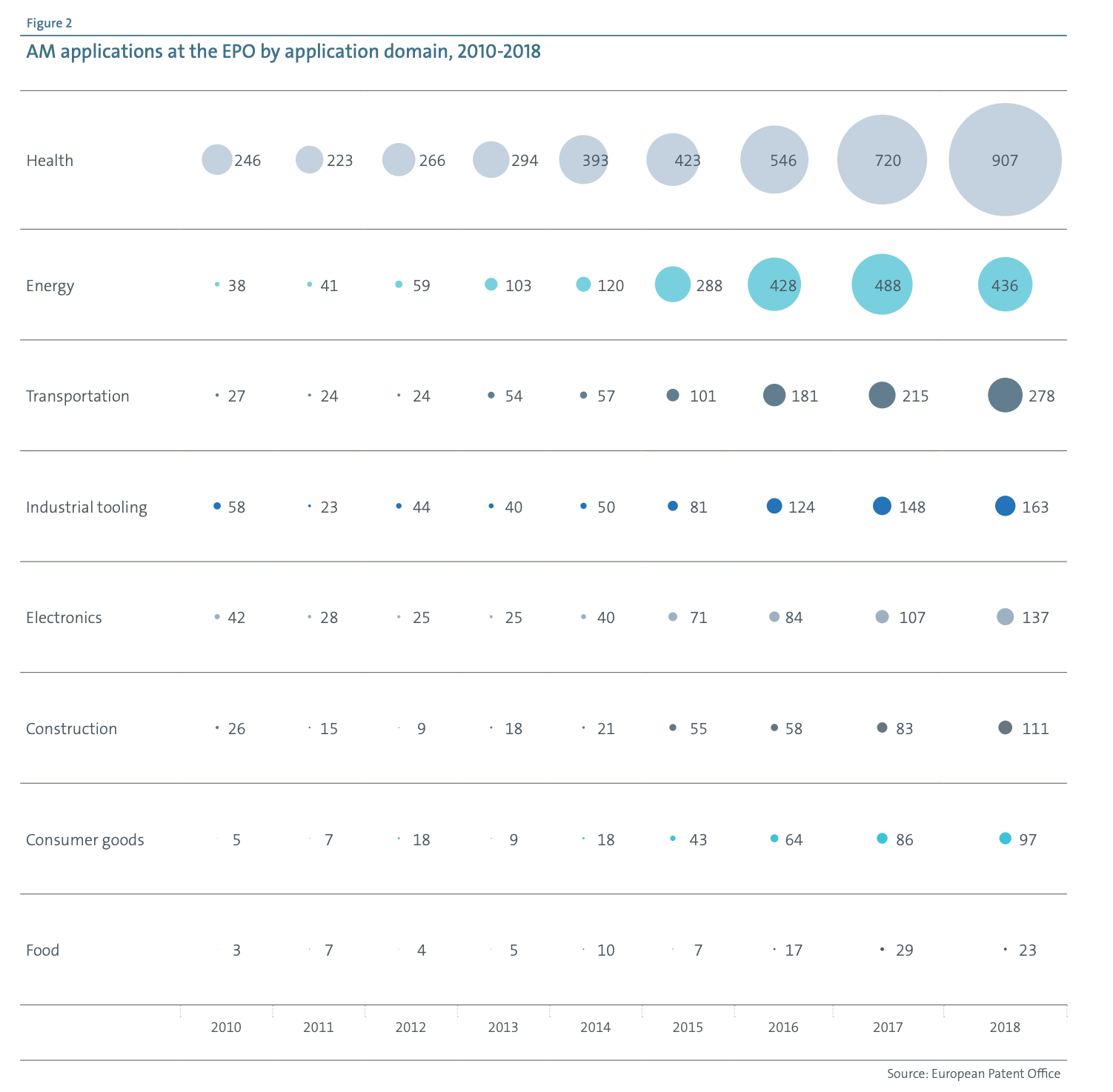

According to the data from the European Patent Office, healthcare accounts for the largest number of additive manufacturing patents, followed by energy and transportation. It also shows that some 46.6% of the 3D printing patent applications between 2010 and 2018 came from Europeans, followed by 34.8% from the US and less than 1% from China.

Practical applications

Healthcare has been one of the key areas driving 3D innovation, with a number of companies cropping up with ideas for how to 3D print materials that mimic living tissue such as blood vessels, organs and bones. Companies include Particle3D (Denmark), Mimetis (Spain) and Xilloc (Netherlands).

Meanwhile, Open Bionics is building a business out of Bristol by 3D printing prosthetic limbs for children.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought some of these 3D printing companies to prominence in a new way, as 3D printing was used in imaginative ways to source scarce medical equipment.

Italy’s Isinnova became famous in March for designing a 3D printed valve that would turn a snorkelling mask into a non-invasive oxygen ventilator. Leuven-based Materialise, similarly, was celebrated in the press for helping Seattle Children’s Hospital create missing medical components.

But even in some of the more niche areas like food, 3D printing is taking hold. Companies like Barcelona-based Novameat and Israel's Redefine Meat are creating plant-based steaks that are 3D printed to look and feel like the real thing. (It is not a million miles removed from printing a material that mimics human tissue, after all).

One of the latest developments comes from a group of Danish students who have developed a way to 3D print a plant-based alternative to a salmon fillet.

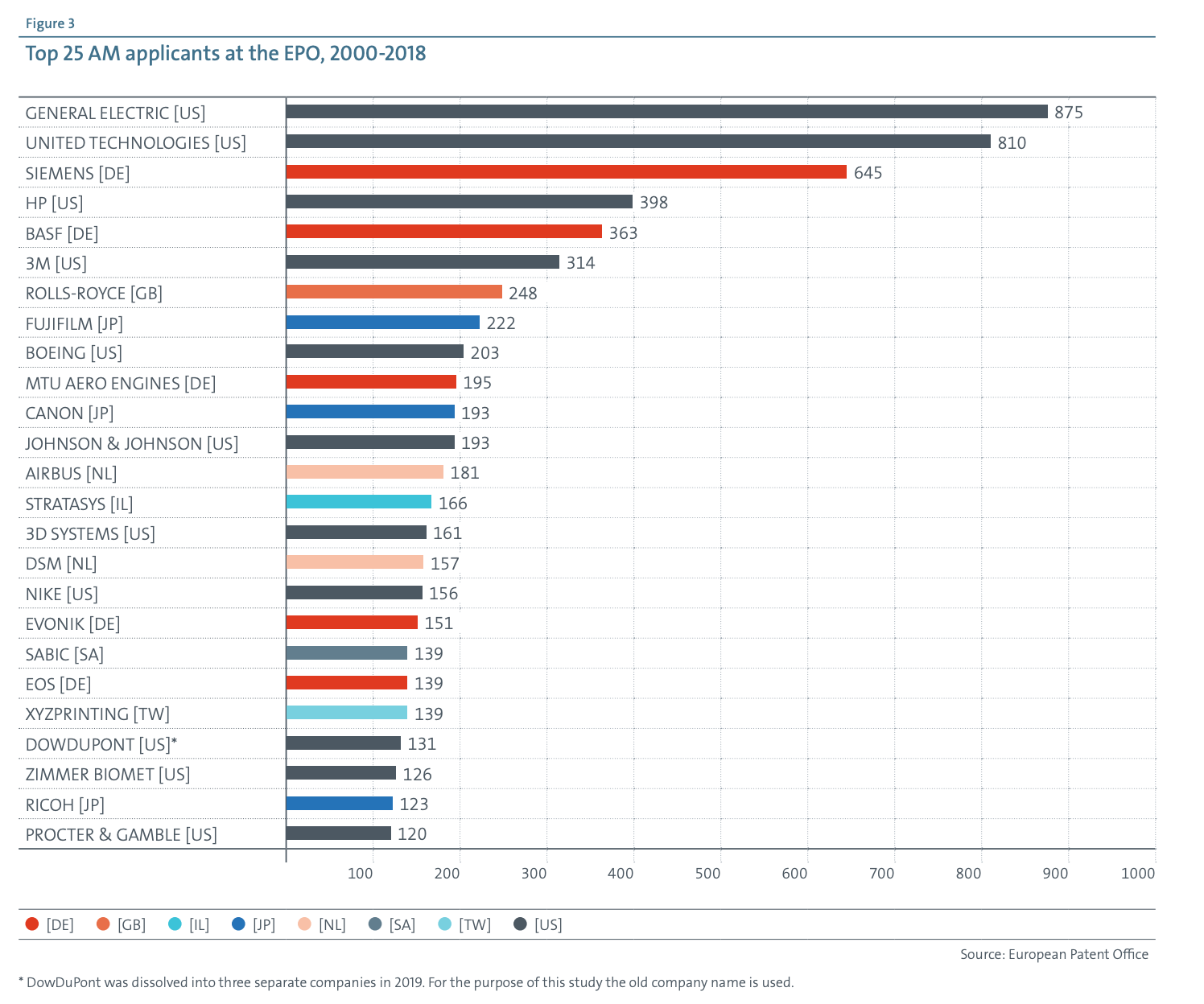

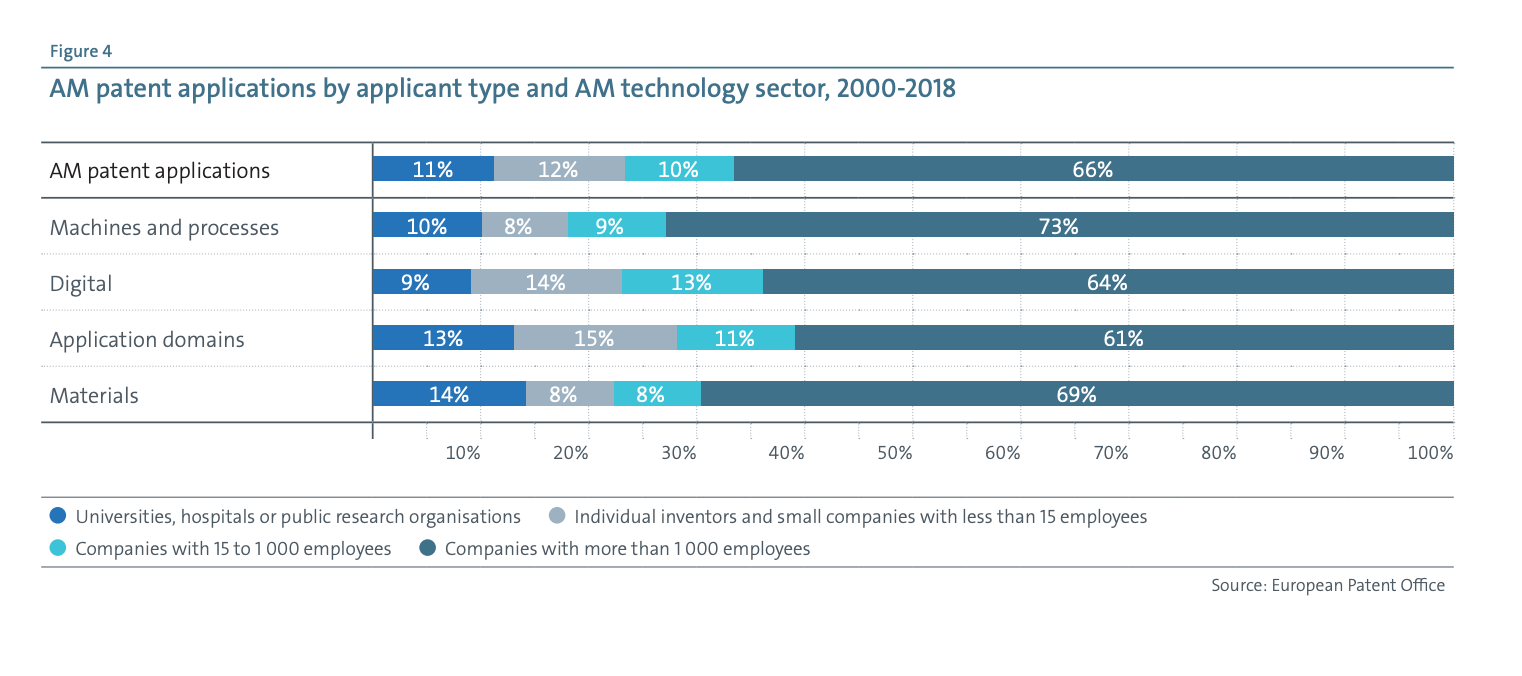

The lion's share of the patents come, unsurprisingly, from big companies, with just 25 companies accounting for 30% of all the applications. Siemens, BASF and Rolls-Royce are among the most prolific of 3D printing patent appliers in Europe.

“3D printing allows you, to a certain extent, to re-internalise part of your supply chain and free yourself from a dependency on transport and logistics,” says Joffe. “Covid-19 will have accelerated the need for that.”

But though big companies may account for the most patents, small companies are also playing a role in the ecosystem — 12% of patent applications are coming from companies with less than 15 employees.