“As a VC I strongly encourage most of the startups I work with to look at the US as they are much more likely to get an exit there,” admits Vin Lingathoti, partner at Cambridge Innovation Capital, which invests in disruptive technologies based in Cambridge.

CIC’s focus is firmly on Cambridge in terms of finding startups with world-class deeptech propositions. But when it comes to finding buyers for them, the VC firm still often finds itself looking across the Atlantic.

It does mean innovation moves away from Europe and it becomes a vicious circle.

“Not enough companies are acquiring here [in Europe]. It does mean innovation moves away from Europe and it becomes a vicious circle,” says Lingathoti.

The phenomenon is particularly strange for Lingathoti, who spent nearly five years working at Cisco Ventures helping Cisco invest in and acquire businesses at a phenomenal rate. The US tech company has done more than 225 acquisitions in its lifetime, around one every six or seven weeks. Since moving to Europe, Lingathoti has been struck by the very different pace of startup M&A at European companies.

“In the US it is not unusual for a company to buy something for $1bn and see how it goes. But I can’t imagine a European company buying WhatsApp for £19bn with just 30 employees or Instagram for £1bn with no revenue,” he says.

The numbers

The numbers spell out the US/Europe difference clearly.

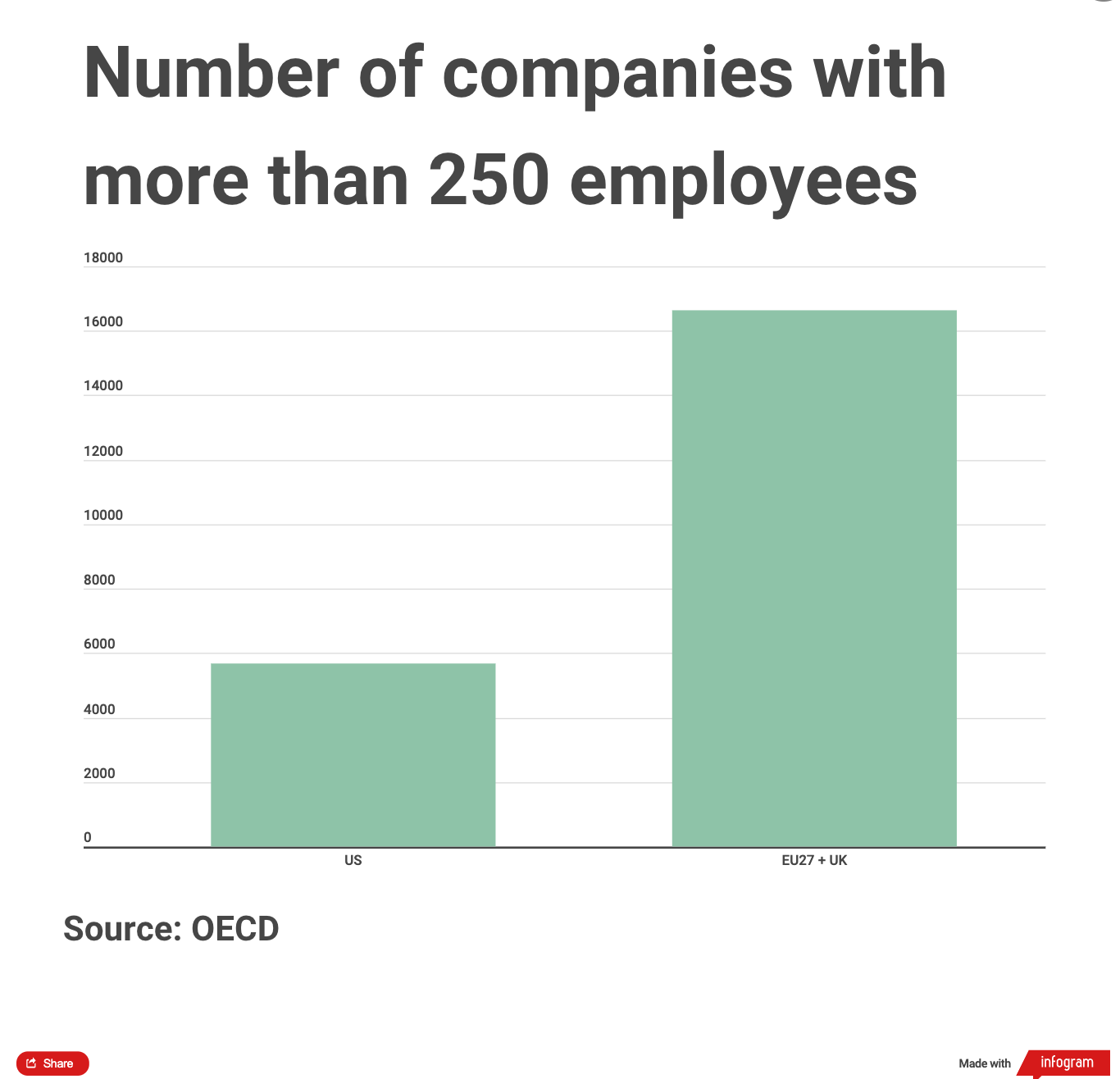

It’s not that Europe has any fewer large companies than the US. In fact, according to OECD figures, it has about 3 times as many companies employing more than 250 people than the US does. But these companies buy far fewer startups.

That is a lot more M&A per company in the US.

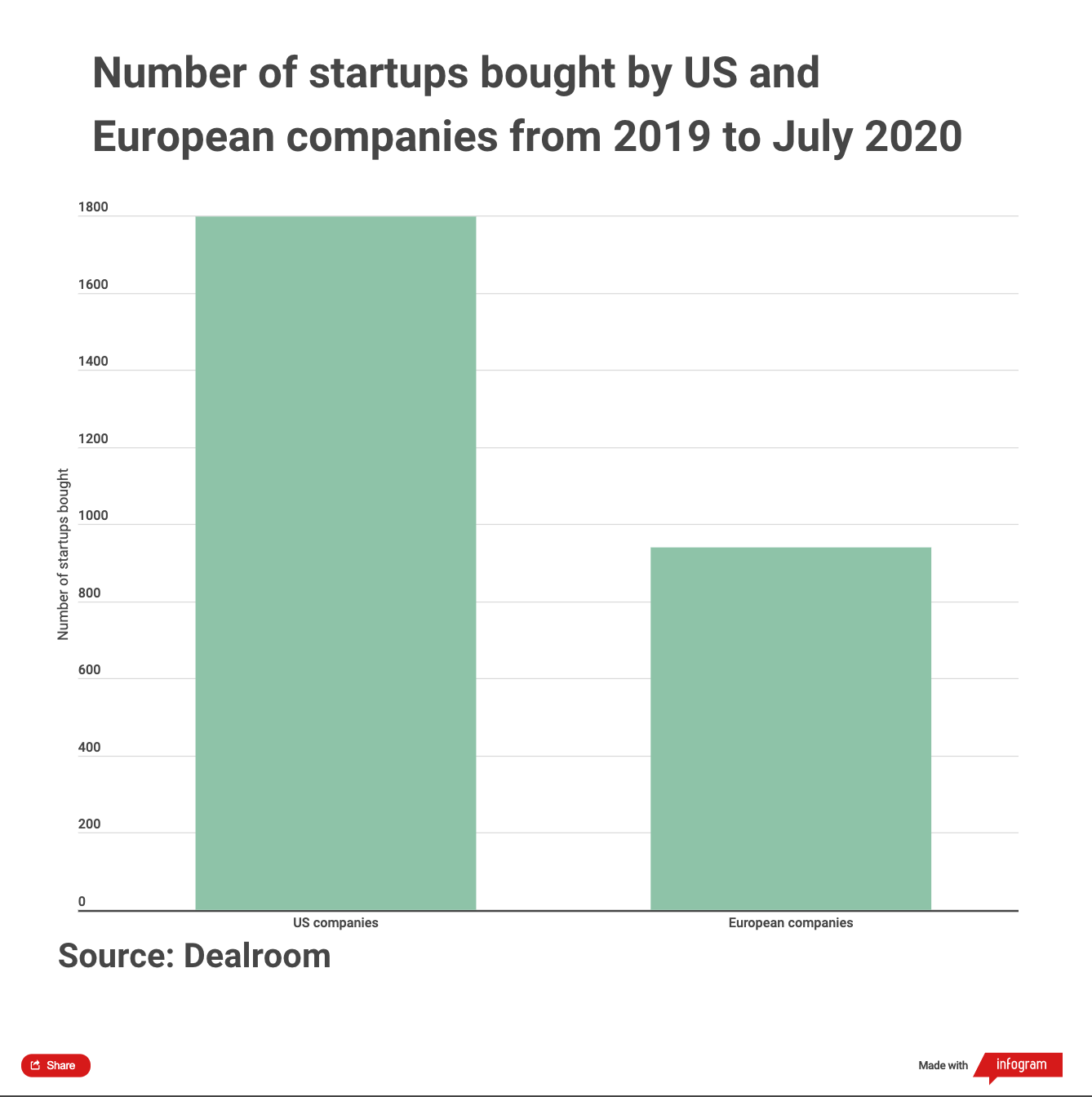

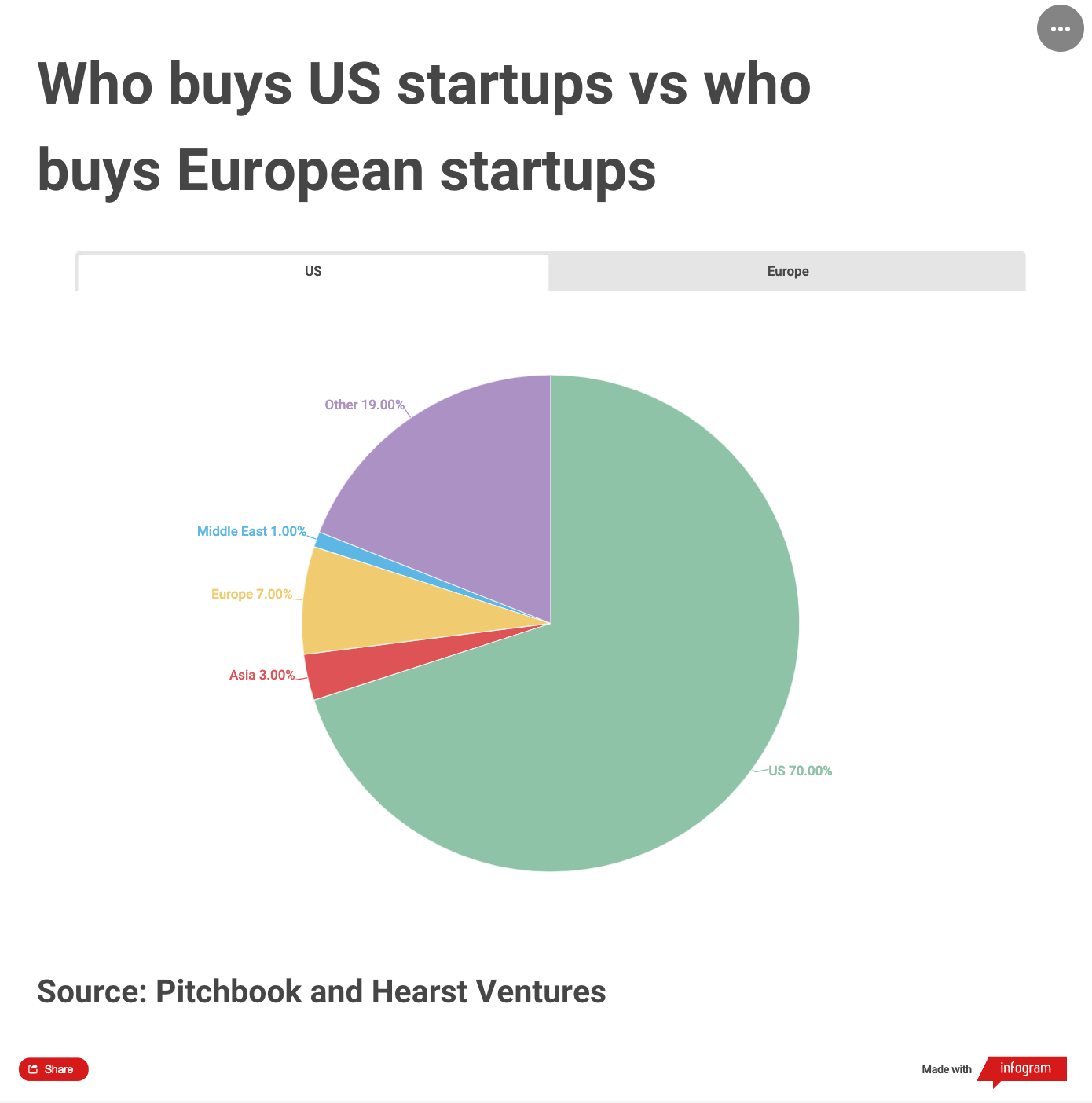

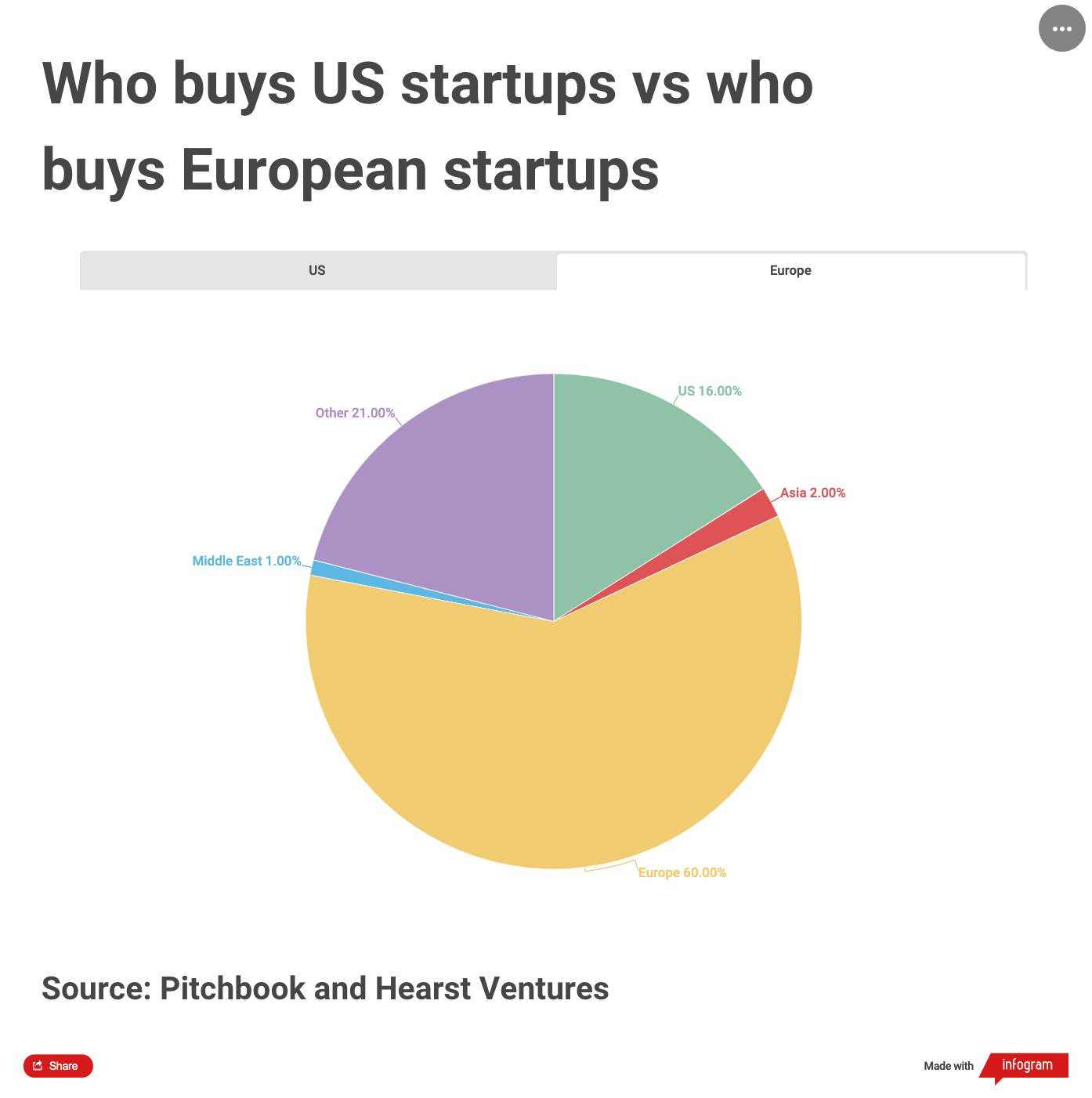

And when US companies go shopping, they are more likely to buy US startups than European companies are to buy European startups. Hearst Ventures analysed some Pitchbook data showing the acquisitions of US and European startups over the last 10 years.

Looking at a particular cohort of startups founded in 2010, the data shows that they were around twice as many deals for US startups (3,761) as there were for European startups (1,990). There was also a marked difference in the pattern of who was buying them. In 70% of the US startup deals it was a US company buying a US startup.

For European startups, a European corporate was a buyer in only around 60% of the cases.

Why does it matter?

Megumi Ikeda, partner at Hearst Ventures Europe, says there are two problems with the lack of European corporate buyers. One is that it makes the market for European VCs less vibrant. With fewer local options to exit, it is riskier for VCs to invest.

VCs need not just the big standout successes, says Ikeda. They also need a market for the smaller, $40m–$50m valuation companies. In the US, companies like Cisco and Intel often buy these as “acquihires” to get hold of know-how and talented founding teams. But such deals are less common in Europe.

CIC’s Lingathoti agrees.

“One of the biggest concerns my team had at Cisco was deploying large amounts of capital in Europe. They were comfortable writing large cheques to Israeli companies, knowing that an exit of 3–5x was very likely. But there have been fewer exits for European companies.”

This means less money, overall, for the European startup ecosystem.

“Selfishly, as a VC I obviously want a bigger market for startups. But there are broader considerations,” says Ikeda.

We talk a lot about technical sovereignty, but that can be a very defensive strategy.

The question of “technological sovereignty” has become a key buzzword for the new European Commission, meaning weaning Europe off dependence on the US or China for key technologies. Commissioner Thierry Breton has been pushing for this in particular.

Much of the “technological sovereignty” agenda has been about channelling EU funding to key areas such as artificial intelligence and tightening rules on allowing foreign companies to buy startups working on sensitive technologies. But Ikeda says that European corporations could also play a key role.

“We talk a lot about technical sovereignty and putting a lot of restrictions in place, but that can be a very defensive strategy. There is a much more offensive approach you can take by embracing the opportunity to buy startups in your region and take the risk,” says Ikeda.

Why are European companies reluctant to buy startups?

Cultural conservatism and other hard-to-pin-down “soft” reasons are often bandied about when people try to work out why Europe lags behind on big tech. These same ones come up again for the lack of M&A.

Lingathoti suggests it might be a question of US stock market investors being more willing to support acquisitive companies. When an acquisition goes wrong in the US, the markets are likely to be more forgiving, he says.

“Cisco had some not-so-lucky acquisitions. But shareholders were more accepting. European shareholders seem less open to failure.”

But Ikeda is sceptical.

“The people who invest in the LSE are largely the same people who invest in the NYSE so this argument wears thin after a while. The composition of who owns Siemens and who owns Intel isn’t all that different.”

Are things changing?

Stephan Lobmeyr, partners at Capital D, a pan-European private equity fund manager, thinks European companies are starting to wake up. He points to the recent deal by Henkel to take a majority stake in Invincible Brands, the direct-to-consumer beauty and health startup.

The deal was, essentially, an acquihire, with Henkel primarily interested in gaining the social media marketing expertise that Invincible Brands had developed. It is the kind of deal that could well be replicated by a number of other consumer goods companies, says Lobmeyr.

Social media marketing needs to become a core competency. Many other European brands are realising this as well.

“They realised that millennials are no longer watching TV or reading magazines, they are spending time on social media. If you are a consumer goods company you need social media marketing to become a core competency. Many other European brands will be realising this as well. It is worth having the skills in house.”

European companies are also becoming more skilled in working with startups. Lingathoti says that US companies such as a Bank of America and AT&T have been ahead of the game in having open innovation programmes to collaborate with startups. Collaborations don’t necessarily lead to M&A — even acquisitive Cisco has tended to buy less than 10% of the startups it invests in — but they do give big corporations a better feel for what startups can offer them.

The new generation of European companies, like Spotify, are buying.

Since 2014 there has been a proliferation of open innovation programmes in Europe, too, and in some cases, organisations such as BMW Startup Garage and Combient Foundry are creating templates where multiple corporations can learn to engage with startups better.

And Ikeda hopes that a new generation of digital companies in Europe will be more acquisitive. Spotify, she points out, has been strongly acquisitive to date, with 17 deals since 2013 (albeit many of them in the US rather than in Europe).

“There are some hopeful signs. The new generation of European companies, like Spotify, are buying, and I am hoping that others like Adyen will do the same.”