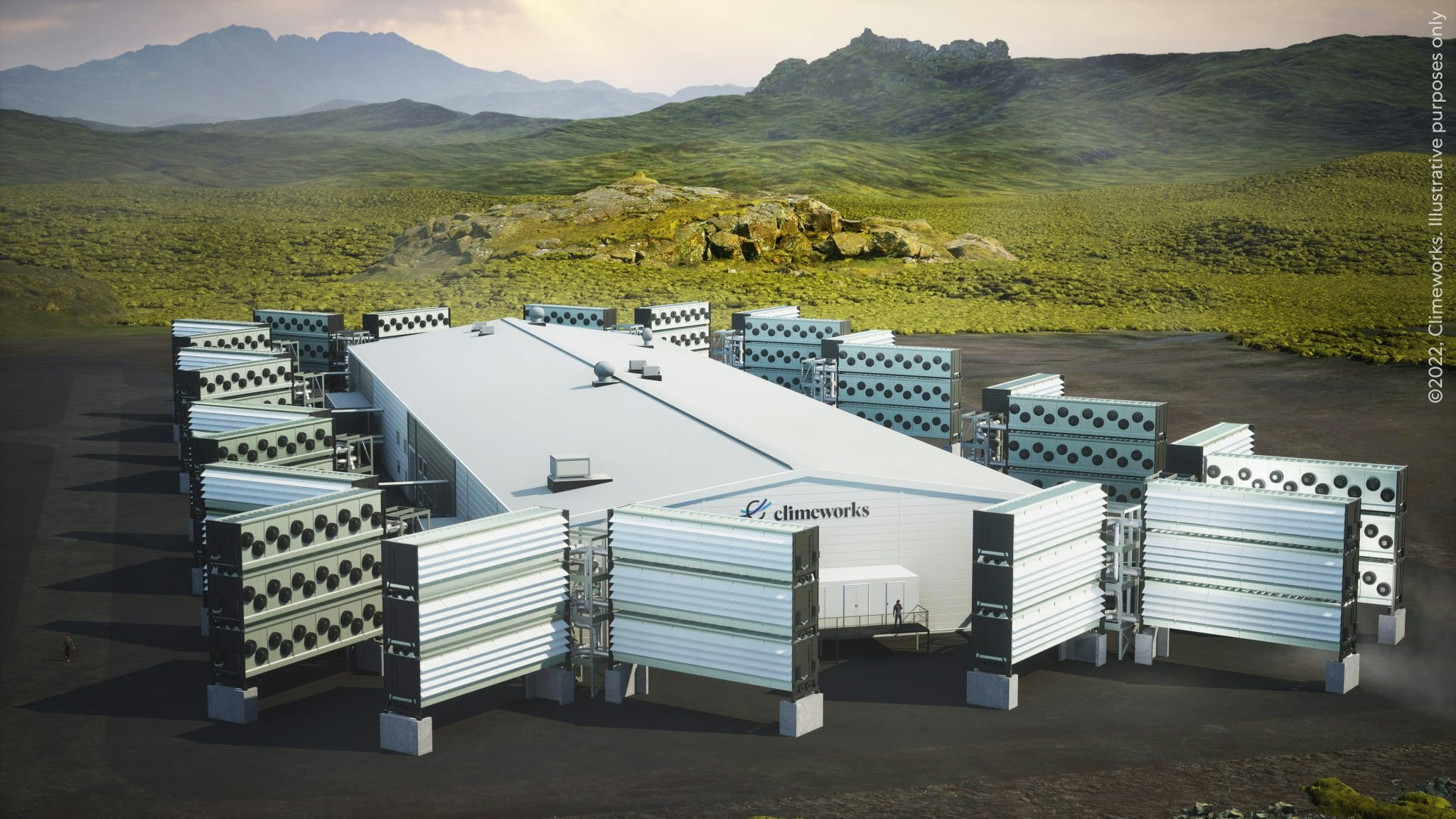

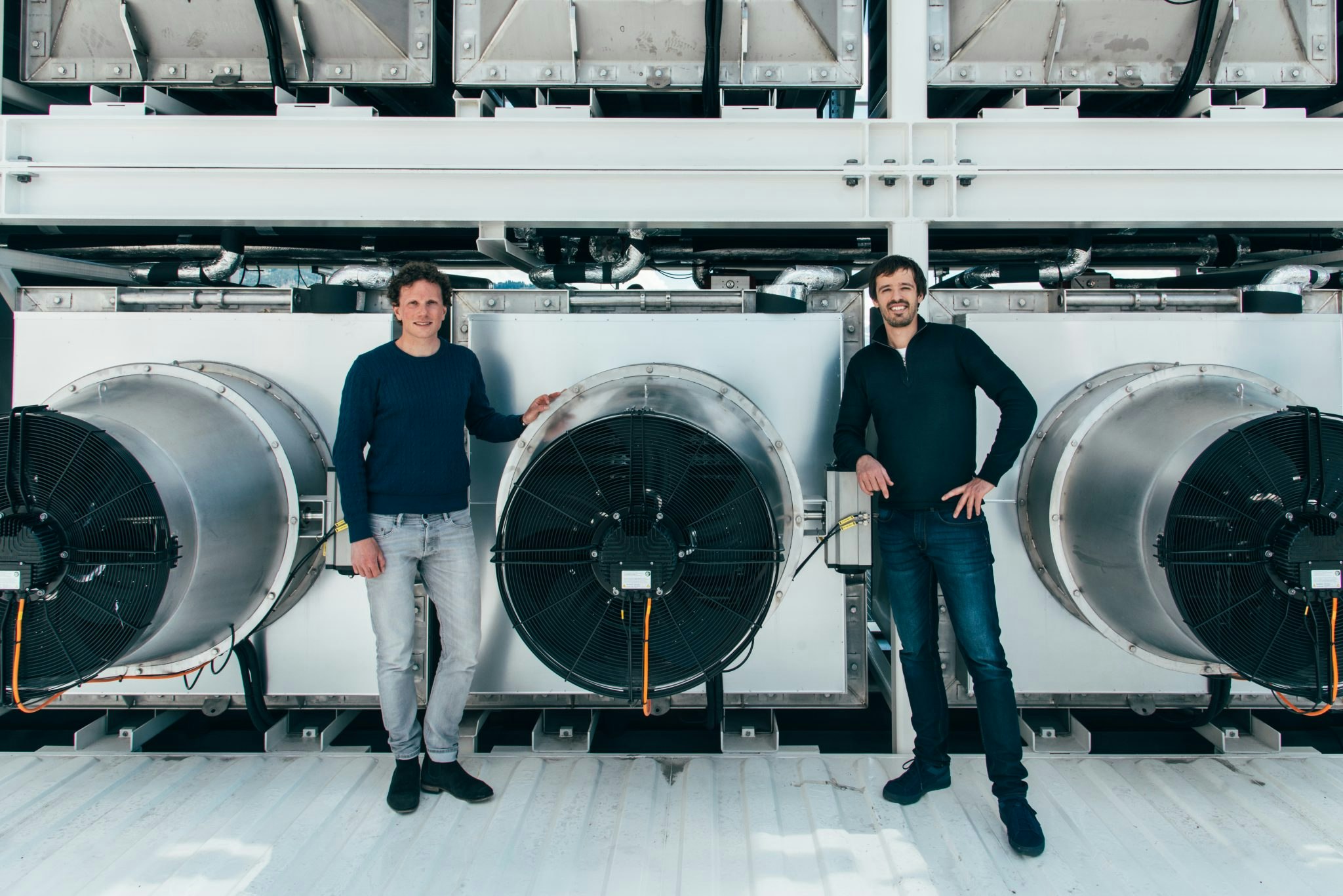

When Europe’s best-funded direct capture company, Climeworks, launched its first plant, it went north — to Iceland. There, Climeworks can run its machines, which remove CO2 directly from the air, off the Nordic nations’ free-flowing hydropower.

For its next plant, Climeworks is heading somewhere significantly warmer and more southern: Kenya. The east African country is fast becoming a hotspot for the deployment of climate tech— and for direct air capture (DAC) in particular.

Great Rift Valley

DAC works by sucking air through giant machines, with filters in them to trap CO2 particles.

The consensus on whether we should deploy DAC is mixed. Some say the process distracts from solutions that prevent CO2 being released in the first place — and that it could give fossil fuel companies license to continue emitting, with the promise of future drawdown. Others say DAC is now necessary if the world is to meet key climate targets.

One thing has almost universal agreement. DAC is incredibly energy-intensive and only makes sense if the process is run off renewable energy.

That’s one of the factors that make Kenya an attractive place to deploy. The country’s grid is run largely off renewable energy, thanks to its position on the equator — meaning significant solar power potential — combined with wind and hydropower.

In the Great Rift Valley, a big, intra-continental crack in the Earth that runs through Kenya from north to south, the earth’s crust is thinner, meaning rich geothermal potential. A by-product of geothermal is steam production, which is used to power DAC machines.

On top of that, the Great Rift Valley also contains certain kinds of rocks that make it easier to inject captured CO2 underground. It’s a crucial part of the DAC process: if CO2 isn’t trapped permanently, there’s no point removing it from the air.

“Kenya presents an interesting trifecta, combining things that you don't necessarily find in a lot of places,” says Bilha Ndirangu, CEO of Great Carbon Valley, a Kenyan company that is setting up two industrial parks for green industry and is partnering with Climeworks.

Alongside DAC, Great Carbon Valley hopes to set up things like green ammonia and green hydrogen production (both of which need renewable energy to run), as well as industries that turn trapped carbon into other products, such as synthetic fuels.

A new generation of DAC plants

Climeworks and Great Carbon Valley have agreed that the first plant will be up and running in 2028. “Initial negotiations aim for a removal capacity of at least 100,000 tonnes and up to 1Mt when fully ramped up,” a spokesperson for Climeworks told Sifted.

For context: in 2022, the world pumped 36.2 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Climeworks isn’t the only European company looking at deploying in Kenya. Sirona Technologies, a Belgium-based startup launched in January this year by former Tesla exec Thoralf Gutierrez, also plans to deploy its first DAC machines in the country.

Deploying in a country with an abundance of renewables means the machines themselves can be simpler, cheaper and easier to produce, says Gutierrez.

“Once you’re in a country with so much solar, you don’t try to build machines that are super energy efficient anymore. You can build machines that are simple instead — very simple machines don’t cost as much, so you can build as many of them as fast as possible.”

Sirona has just finished making its third prototype machine and hopes to begin mass manufacturing in Belgium at the end of 2024. The speed at which it’s possible to deploy in Kenya is also a draw, Gutierrez says.

“In Europe, permitting is extremely slow. That’s why we’re excited about going to Kenya, because the government is extremely supportive and they can move quickly.”

In November, Kenyan President William Ruto called carbon credits (the mechanism by which companies pay for DAC) an “unparalleled economic gold mine” and his country’s “next significant export”.

The Kenyan government’s relationship with carbon credits is controversial — human rights lawyers say communities have been removed from their ancestral lands so forestry-based carbon offsetting schemes can be set up.

Africa’s role in climate change solutions

The majority of companies looking at deploying DAC in Kenya are from the Global North, says Great Carbon Valley’s Ndirangu. As well as European companies, there are those like Cella Mineral Storage, a New York-based company, working on CO2 storage in Kenya.

“It’s not surprising because a lot of the technology and research and funding happens in the Global North,” says Ndirangu. The aim behind Great Carbon Valley is to show that the Global South, and Africa in particular, have the right conditions for deploying that tech, she says.

“Africa has been portrayed as a victim of climate change, which is true. We only produce 3% of emissions, but we’re heavily affected by climate change,” Ndirangu says. “But at the same time, Africa has a lot to offer in terms of climate change solutions, and that narrative didn’t exist for a long time.”

But should heavy-emitting countries outsource emissions removal to very low-emitting countries? And, given that most companies deploying DAC have their headquarters — and bank accounts — outside of Kenya, how much guarantee is there that the country will share in the profits of this new industry?

Ndirangu argues that the job creation potential is large — which is important within a country with a high unemployment rate, particularly among people under 29. The country would also benefit from the taxation of carbon credits when they’re bought by companies overseas and exported, she says.

Ndirangu’s hope is that the influx of companies from Europe and the US will inspire local innovation too. “We’re looking to build a sandbox that makes it easier for local innovators to deploy solutions,” she says. “As you have these solutions being deployed here, you’ll start to have local engineers getting exposed to these technologies — and then can innovate on them.”