When Covid-19 hit Europe, medics working in pretty much every healthcare system wished they were just a little bit more... Estonian.

While doctors from Basingstoke to Bern found themselves adapting to a whole new way of giving consultations within weeks, and pharmacists were searching for a way to prevent vulnerable people queuing outside their stores to pick up their weekly medications, in Estonia it was business as (sort-of) normal.

Estonia’s health service has been digital for 12 years. More than 99% of the data generated by hospitals and doctors is digitised. Citizens can access their own medical records via a super-secure online portal and choose who gets to look at those records. That means finding out whether or not you’ve had a jab for yellow fever is a few clicks away, as is discovering just how many millilitres of a particular drug you were given when you had your tonsils taken out.

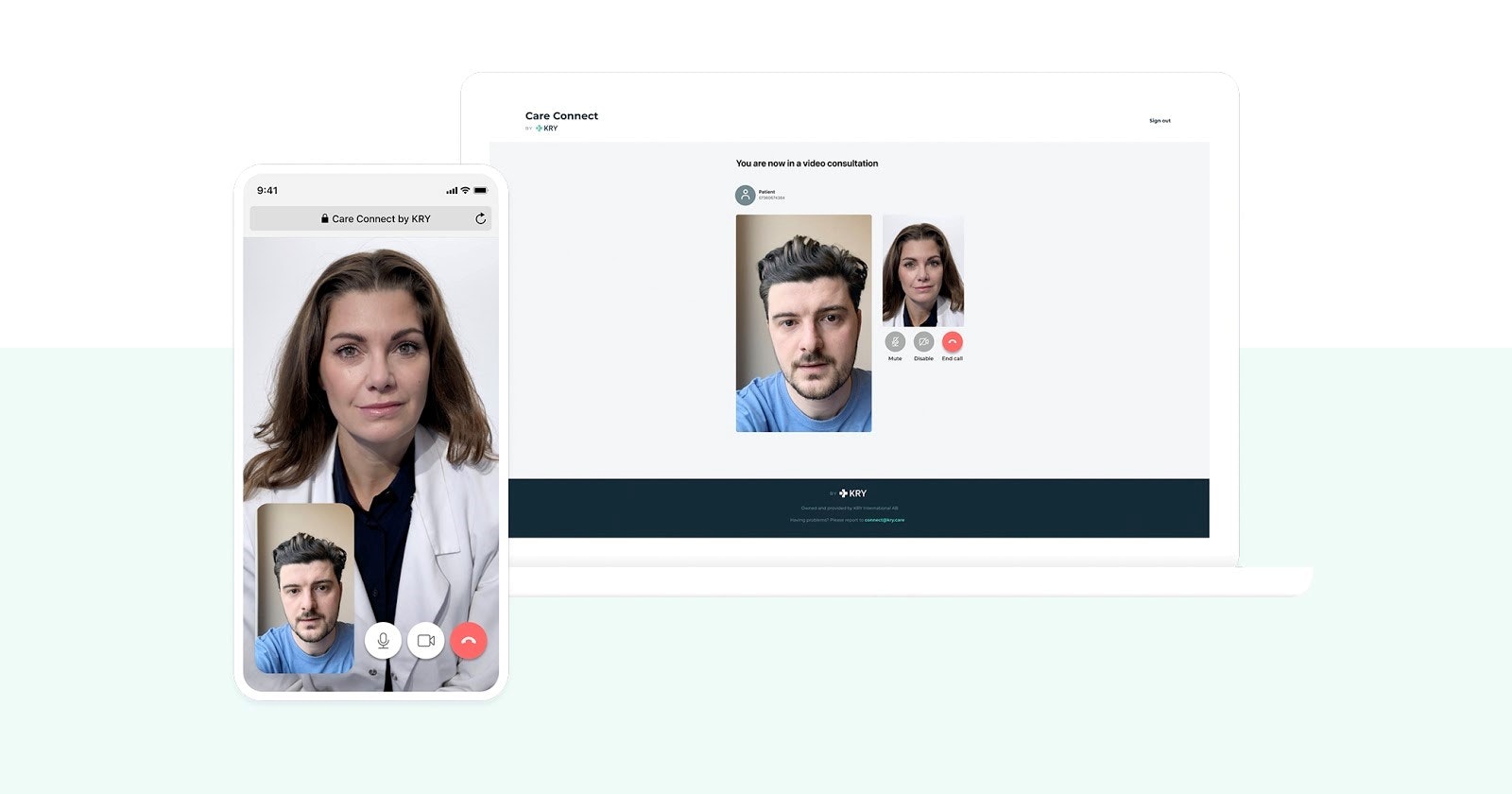

Many health services also happen online — from video consultations to e-prescriptions. And things that can be enormously complicated elsewhere, like registering a death and notifying all the relevant parties, are seriously simple; in Estonia, once a death is registered online, notifications are automatically sent to that person’s workplace, the tax office and the population registry.

For many people involved in less digitised health services, all that sounds positively futuristic.

But, perhaps, it’s not so futuristic after all. If other health services were looking for a moment to push forward a radical new way of doing things, they’ve found it.

Crisis-ready

“We were already prepared for the crisis,” says Anett Numa, digital transformation advisor at e-Estonia. Her job is more or less to explain how brilliant Estonia’s e-government is — and help others figure out what ideas they could pick up.

We were already prepared for the crisis.

At the moment, other governments are especially interested in how remote prescriptions work, Numa says. “It’s one of the biggest problems countries were facing — people couldn’t get access to medicine they needed to have.”

But in Estonia, it was simple. People were able to call up or email their doctor and ask them to issue a prescription. They didn’t have to physically visit a pharmacy to pick it up, either; they could log in to an e-pharmacy and order those medicines to their home for a few euros. 99% of prescriptions are digital.

Doctors and patients can communicate pretty easily in Estonia — another thing that seriously impresses other governments, says Numa. “There’s huge transparency,” she says.

People can ‘lock’ or ‘unlock’ medical records, which is useful in many ways. Take someone who has received a bad diagnosis from one doctor, and wants to get a second opinion, says Numa: “They wouldn’t want the second doctor to see the previous analysis.” They can ‘lock’ that diagnosis, and get a completely unbiased second opinion.

Trustworthiness is built into the system’s design. Every time someone accesses a patient’s information, it is logged. “No doctor is able to go ahead and check my medical records just for curiosity,” explains Numa. This logbook ensures that everyone uses the system as they should — and means that just 500 people out of Estonia’s population of 1.3m choose to ‘close’ their entire records each year.

Make people understand that they are the owner of their data. That’s the biggest thing.

For other countries worried about how their citizens would react to new digital initiatives, Numa has one big piece of advice. “Education is an answer to everything,” says Numa. “What I’d suggest to every government is to try to educate your people. Say how these things have been built. Tell them the background story. Give them chances to control their information, and make people understand that they are the owner of their data. That’s the biggest thing.”

Estonia also tries to involve its citizens in key decisions about the system. Accelerate Estonia, a state-backed innovation platform, frequently runs hackathons where startups can design new tools for the digital government — most recently, ‘Hack the Crisis’, a virtual two-day event in March where 1000 people developed digital solutions to help during the pandemic. Winning solutions included a platform to connect vulnerable people to volunteers offering to help them out, another was a workforce sharing platform that connects unemployed or furloughed workers with companies in need of additional staff.

“There’s a community feeling — we can help each other,” says Numa. And that all feeds in to helping citizens feel comfortable with using digital government tools. “If a person feels like their opinion has been considered — if they can give feedback, and develop their own ideas — then they feel a part of this and are willing to use this.”

Personalised future

Looking forward, Estonia wants to offer much more preventive healthcare too.

To aid this, it has been offering people free gene tests since 2018, and the Estonian Genome Centre has so far collected data from 200,000 citizens — over a seventh of the population. Doctors can use the information from these tests to work out if people are in high-risk groups for certain diseases — and could in future send them reminders to get relevant check ups.

Such information will also help Estonia better plan, prioritise and even minimise healthcare spending.

“If we had even more data, we could see which illnesses Estonian people suffer from the most,” says Numa. “I’m dreaming here — but we could make decisions based on this. We could recommend what children should eat at school.”

If we had even more data, we could see which illnesses Estonian people suffer from the most.

All this might sound expensive, but Estonia spends just 1% of its state budget developing tech — and new solutions generally pay for themselves within four months, says Numa.

Not everything works perfectly, however. “Of course, there are some things that should be working much better,” admits Numa.

Estonia is currently developing a national e-booking system — and “it’s not going as well as planned”. Doctors have been kicking up a fuss; they’re worried that if patients can book in appointments themselves, they’ll lose control of their schedule.

Yet, challenges aside, the rest of Europe needs to up its game, says Numa. “It’s really time for the EU Commission to start dealing with these things; we need a central way of exchanging medical records as soon as possible. With the crisis, that would’ve been a huge help.”

“It’s time to wake up.”