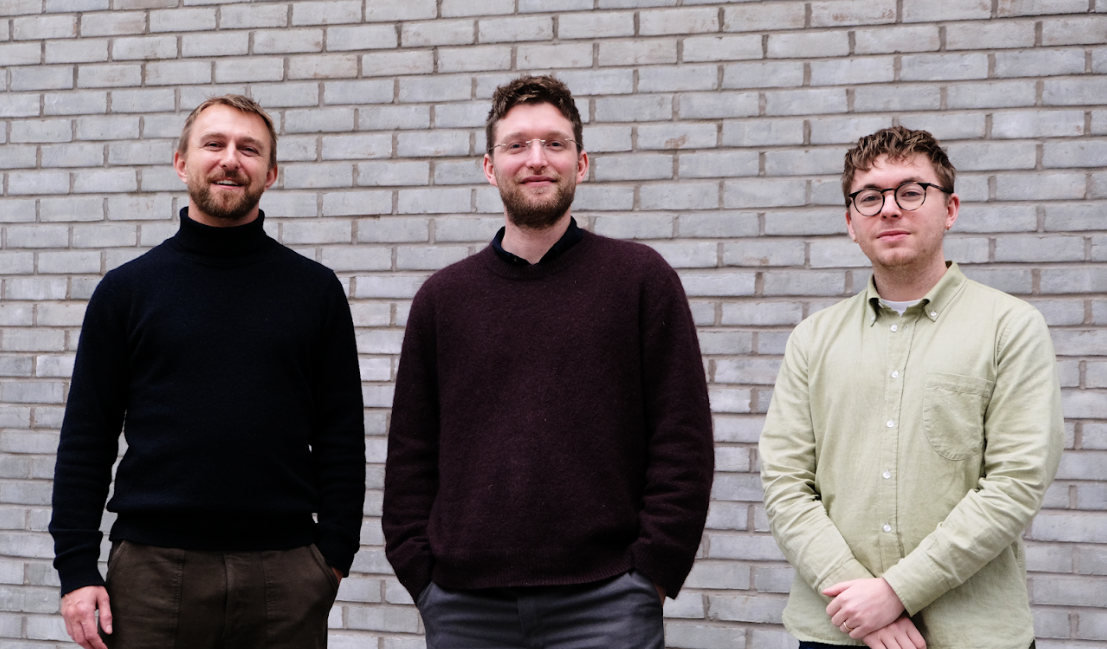

There’s nearly a 50-year age gap between the two cofounders of Epoch Biodesign.

Jacob Nathan, cofounder and CEO, is 21. At school, he got interested in the fact that our planet’s heading for catastrophe — specifically the plastic waste problem — and wrote a paper on how enzymes could be used to break down hard-to-recycle plastics.

Next, he went online to find a scientist who could work on the topic. He found Douglas Kell, a professor of systems biology 48 years his senior, and together they started Epoch Biodesign.

Three years later, they’ve just raised an $11m round, led by Lower Carbon Capital.

Plastic-eating enzymes

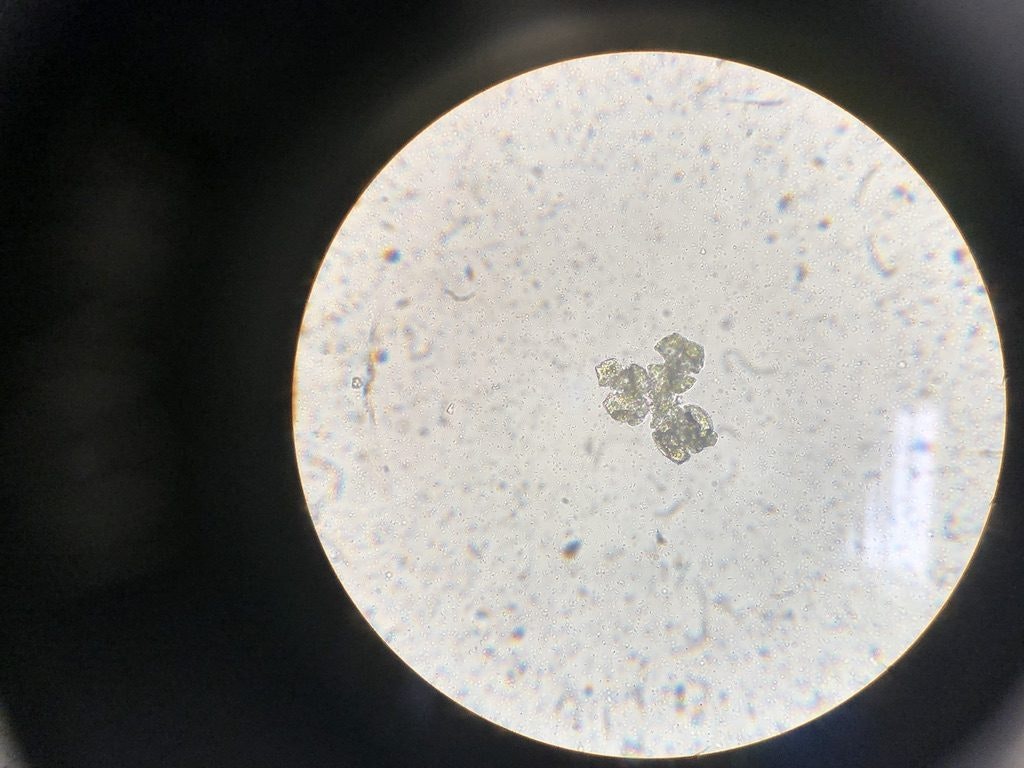

Kell’s academic work had focused on developing tools to engineer enzymes — proteins which produce chemical reactions — towards specific uses. Epoch Biodesign is using those tools to iterate on an enzyme specifically able to break down plastics.

“We programme microbes to produce an enzyme. Then we produce it in a similar way to making beer. Instead of brewing ethanol, the alcohol molecule, we brew the enzyme,” explains Nathan.

👉 Read more: 13 startups tackling the global waste problem, according to VCs

The team has already produced enzymes that can break down plastic, but the task now is about producing one that can do it in the quickest and most economical way possible.

Epoch Biodesign is targeting plastics that are currently unrecyclable — things like multi-laminate packaging, flexible films and plastics used in agriculture and manufacturing.

The bio revolution

Epoch Biodesign’s work is part of the broader synthetic biology industry — an industry that’s getting investors and scientists increasingly excited.

There are 400 use cases of synthetic biology, McKinsey estimates, all based on redesigning organisms that can then be brewed to create useful things — everything from new materials to energy and health applications.

Cultivated meat is one example, as is precision fermentation: where yeast proteins are redesigned to produce a product similar to cow’s milk through a brewing process.

“Instead of extracting, we're going to brew everything,” says Nathan.

The business case

The output of the enzyme process can also be used to create new materials — things like cleaning products, fertilisers, multi-use chemicals and adhesives.

“This approach is good from a cleaning up plastic perspective, but we're also unlocking a new feedstock for the world to produce things from,” Nathan says.

Epoch Biodesign’s plan is to build and run the first plastic-eating plant. At present, companies pay to send their plastic waste to landfill or incineration facilities — Epoch Biodesign is aiming to be cheaper than that to incentivise companies to use them instead.

Beyond that, the idea is to partner with companies looking to create circular economies within their manufacturing.

My ultimate vision for this is that we can decentralise recycling completely

“Our ideal partner is somebody who can both supply us with plastic, but who we can also sell chemicals to,” explains Nathan.

“So one example could be if a company like Unilever wants to make its cleaning product out of its own recycled plastic coming from its warehouses: we can enable that for them.”

The team are also talking to a textile company about the possibility of breaking down clothing waste and turning it into fertiliser that’s then used to grow the cotton plants needed to produce clothes.

Nathan predicts that we’ll see numerous facilities operating enzyme-enabled circular economies within the decade.

Epoch Biodesign also plans to sell its enzyme perfecting technology approach to other companies working on synthetic biology applications.

Plastic-eating enzymes in every home

“My ultimate vision for this is that we can decentralise recycling completely,” says Nathan. “We could do this in the home on a very, very small scale. That's the beauty of biology, it can work at a very small scale.”

Every household could have an appliance which people feed their plastic waste into. It would then use enzymes to turn it into a liquid, which would then be collected and reused.

“I don’t know quite when a world like that is going to happen,” says Nathan, “but I’d like to live in it.”