This is the final part of our series mapping the European startups challenging Elon Musk’s empire. Part 1 was about cars, Part 2 was about the hyperloop, Part 3 was about space tech, and Part 4 about neurotechnology.

This summer, US business tycoon Elon Musk overtook French luxury tycoon Bernard Arnault — the only European in the top five — to become the world’s fourth-richest person according to Bloomberg.

He stands behind three other American technology entrepreneurs — Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Microsoft’s Bill Gates and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg — all of which have created category-defining and inordinately powerful global tech companies from scratch.

Musk alone has created an entire ecosystem around him, and it’s worth billions of dollars, with technological innovation spanning from Tesla’s cars to Space X — something no European entrepreneur has ever done on the same scale.

It has once again raised the question amongst Europe policymakers who are pushing hard to finally make Europe a player in the global tech race after decades of being dominated from abroad: why is there no European equivalent of Elon Musk?

Sifted’s deep-dive

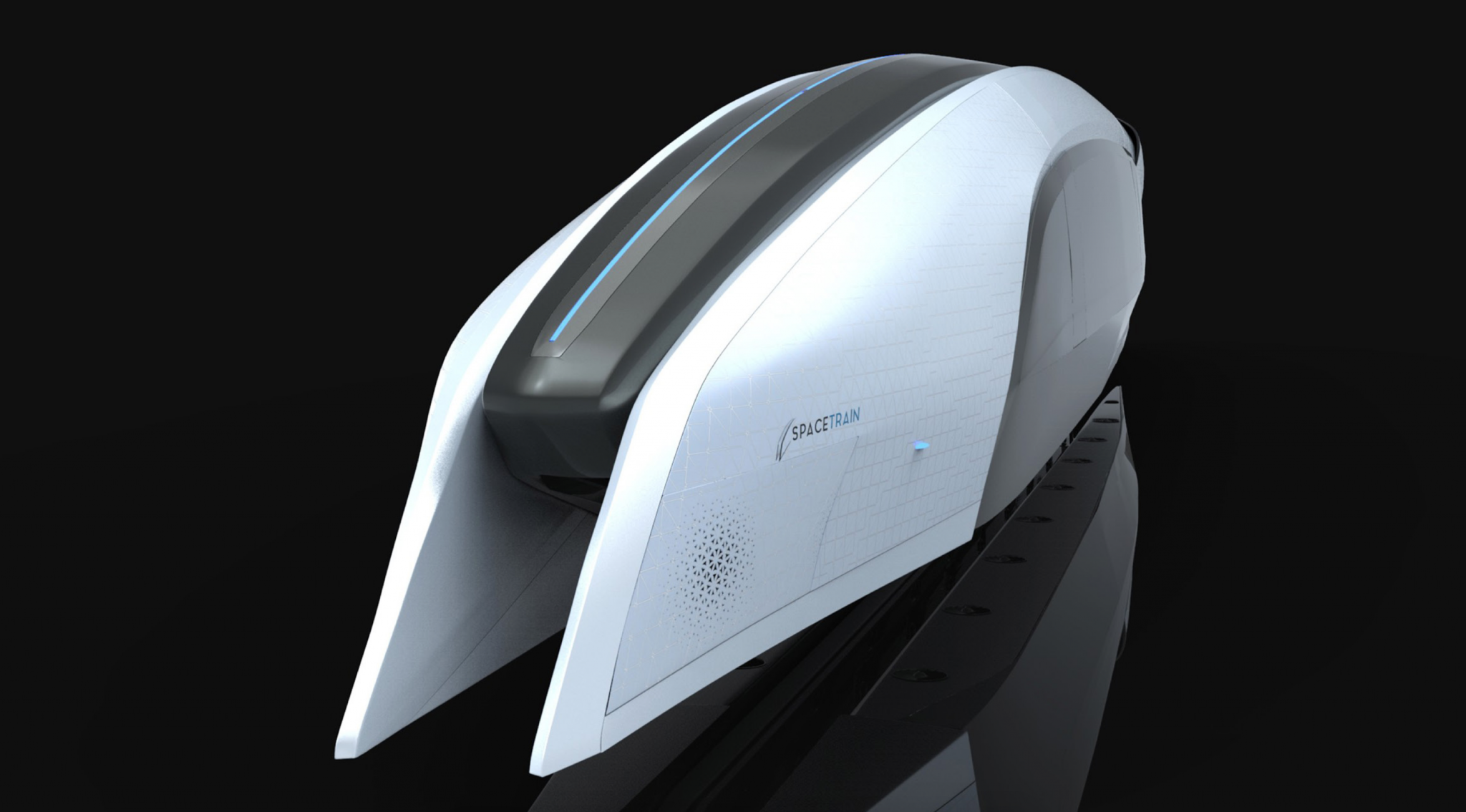

In recent weeks, Sifted took a deep dive into the European startups challenging the Musk empire from cars and batteries, to hyperloops, space rockets and brain tech. We highlighted dozens of innovators, from Sweden’s Northvolt to Italy’s D-Orbit and Spain’s Zeleros.

These startups in a sense show the progress Europe has made. Many of these companies, according to some observers at least, have better tech than the Musk equivalent, particularly in the field of electric cars and batteries.

And many observers also believe that Europe as a continent can over the next decade become a global leader in everything deeptech, further challenging the might of Musk and the other US and Asian tech giants.

“We were too much the followers in internet-related technologies” Gianpiero Lotito, the president of the European Tech Alliance, an industry lobby group, tells Sifted.

Deeptech offers Europe the chance to be stronger again.

“Deeptech offers Europe the chance to be stronger again. We have already shown that we can create some market champions. If we can create the right conditions there is no reason that things couldn’t change in the next three to five years.”

Lotito points out that in the 1990s and early years of the millennium. European telecoms companies like Nokia and Ericsson were the dominant force in technology, and there is no reason the same could not happen again.

Europe has spent recent years trying to build on its talent pool of mega-brains and top-notch engineering and maths whizzes.

As a result, the region now has experienced entrepreneurs who are angel investors and repeat founders, and thanks in part to money from governments and the EU, it has managed to boost the amounts investors are pledging to European-grown innovation and startups.

Key word: fragmentation

One problem is likely to persist though: it’s all just too dispersed.

Today, despite all the great tech out there in braintech, spacetech, electric cars, result is a collection of small fragments instead of one big bang.

This is a well identified problem in Europe. The idea that countries from across the region aren’t able to come together and form a single market has plagued industries from telecoms to defense for decades.

Despite efforts by policymakers to establish a single market, including in the digital space, too many differences persist in areas like taxation and national legislations, consulting firm McKinsey pointed out in a paper about European innovation last year.

The extent to which that fragmentation is hindering the production of globally significant innovation — players who can hold their own against the likes of Google — is at the heart of concerns raised by policymakers.

European Commissioner Thierry Breton made a push to coordinate a 25-country alliance pledging to build a European cloud. It was unveiled earlier this month.

Some think that this is never going to make a substantive difference, and that we will end up making piecemeal advanced that eventually get tied together by someone else.

There’s probably never going to be a European Tesla or Elon Musk.

“There’s probably never going to be a European Tesla or Elon Musk,” says Francois Veron, the cofounder of investment fund Newfund. “There’s room for European players that provide high added-value and make up parts of the overall picture — links from the chain.”

But some believe that there are some ways for Europe to come together over the coming decade and escape the fragmentation trap and maybe even one dad get our own version someone with an empire like Musk.

Ways forward

Sifted interviewed dozens of entrepreneurs, investors and policymakers to produce our series about Musk’s challengers. Here are some ideas that emerged from those interviews on how Europe can make it out of the fragmentation trap.

-

Sustainability as a common goal

“Europeans need common themes to bring them together, and reduce fragmentation,” says Shiva Dustdar, the European Investment Bank’s head of innovation finance advisory. “Sustainability could be that common theme.”

The idea that Europe can spearhead “tech for good” innovation and use sustainability as a differentiator for its technology on the global stage is increasingly popular. There are a growing number of entrepreneurs and investors setting out to prove that Europe can create alternative models for tech innovation that are both profitable and good for society.

Lotito belived that the European “green deal” is creating a situation much like in Silicon Valley in the 1980s when the personal computing revolution was beginning to build.

“Everyone knows what the challenge is and there is a lot of enthusiasm from a group of new companies,” he says. In some ways, Lotito adds, the fact that Europe is starting as the tech underdog can be an advantage. There is less mature market baggage to get in the way of trying out new ideas.

The sustainability theme is now the topic of a yearly conference by French President Emmanuel Macron. BlaBlaCar founder Frederic Mazzella has organized roadshows in the US to talk about it too.

Can it be the banner that unites Europeans?

-

Procurement boost

For Iceye’s founder Rafal Modrzewski, the root of the problem in Europe is about customers — and more specifically government agencies in the region not handing out enough contracts to local companies.

“You can quite easily track SpaceX’s customers by looking at SpaceX revenue. The vast majority of it comes from the US government. It’s either NASA, Department of Defense, or other governmental bodies,” Modrzewski says. In Europe, with the lack of government agencies buying services from the local space startups it is difficult to grow, he says.

The EIB’s Shiva Dustdar agrees. “The procurement power of Nasa, putting hundreds of millions on the table, as well as deep Darpa budgets coming from defense to space — those make a difference,” she says.

“In Europe, there’s a fragmentation of European space agencies. There’s not a homogenous European space agency as we’d like to see it.”

But it’s not just space. The complexities of military tenders and the kinds of clearances required to supply the army tend to make defence contracts inaccessible too for startups going at it alone in Europe.

Other entrepreneurs in different sectors have expressed similar concerns, including about government contracts in segments like cloud and IT.

In France, founders called out Macron at an event last month to voice the idea that what the ecosystem needs most isn’t more funding from the state, but rather that more business and contracts be handed out to French and EU startups.

The European Tech Alliance’s Lotito says Europe’s problem has been an overly-fastidious stance on government procurement, which has made it hard to support local companies.

“We have tried to be so completely neutral that we have not supported companies in a way that is completely normal in the US and in Asia. Companies like Cisco have thrived because the US government gave them a big role in building the backbone of the internet,” Lotito told Sifted. “We are not talking about protectionism, but making the same competition conditions apply here.”

-

Europe needs its own DARPA

For Andre Loesekrug-Pietri, the founder of JEDI, part of the solution is making sure Europe has its own unit inspired by the US Defence department’s moonshot innovation unit DARPA, which invented much of the technology behind the internet, GPS, Siri and driverless cars.

In a more bottom-up approach, Pietri is convinced more cooperation should take place between the researchers, entrepreneurs and experts who are best placed to come up with disruptive innovation.

He set up JEDI last year to bring innovators from across the continent together more, and get them to work on central themes that are priorities for the entire region. Topics from Covid-19 to so-called “deepfake” videos.

“If Europe can facilitate scaling for its startups, we’ll see a boost in valuations,” says Loesekrug-Pietri. “But for that to happen the continent needs to be more pragmatic and less driven by ideology.”

Set up around an initial group of 15 participants in 2019, JEDI now boasts more than 3,700 people.

-

More industry alliances

Startups and well-established corporates should partner more: not only does that help overcome fragmentation, it also cuts back on the amounts of money that need to be invested to build a new technology from scratch.

“Silicon Valley was better than Europe at software. But when it comes to manufacturing and production we are better than the US,” says Navarro Vedreno of hyperloop startup Zeleros. “We have a lot of hidden champions, suppliers who are the best in the world at making some particular part.”

Some argue, however, that European corporations are not playing their part. There are more big companies in Europe than in the US, but European companies have been slower to work with startups and more reluctant to buy them. (We explored the numbers in this article recently.)

“Not enough companies are acquiring here [in Europe]. It does mean innovation moves away from Europe and it becomes a vicious circle,” says Vin Lingathoti, partner at Cambridge Innovation Capital and a former investor at Cisco Ventures.

“In the US it is not unusual for a company to buy something for $1bn and see how it goes. But I can’t imagine a European company buying WhatsApp for £19bn with just 30 employees or Instagram for £1bn with no revenue,” he says.

The lack of corporations willing to buy startups has a chilling effect on the European startup market overall, says Megumi Ikeda, partner at Hearst Ventures Europe. VC investors can be more reluctant to invest in companies when the exit options are limited.

Many of Europe’s most successful corporate venture funds — such as Next 47, AV8, Propel and Sapphire Ventures — based themselves primarily in Silicon Valley and have only more recently extended operations to Europe.

And European companies can be slow even to strike up partnerships with startups. Sifted recently interviewed Martin Schichtel, founder of Kraftblock, an innovative German thermal storage startup. Kraftblock’s customers tend to be industrial companies and Schichtel told Sifted that customers outside of Europe tended to move much faster in trying out the technology. Talks about a pilot project with one German steel company, for example, had yet to produce results after two and a half years. In contrast, a Chinese steelmaker had moved from initial contact to starting construction on a pilot in half a year.

-

Mobiling European consumers

“We have one great advantage in Europe. We have 450m citizens who are consumers and users of technology. This is the richest market in the world, but we need to understand how to put this strength on the table as an advantage,” says Lotito.

One of the reasons that Google became the dominant search engine globally was because it won huge popularity in Europe. In the US the battle with rivals like Yahoo were much more closely-fought; even today, Google’s market share is higher in Europe (90%+) than in the US (80%+).

It is not that European consumers should be encouraged to be protectionist and “buy European”, but startups should recognise that European consumer tastes can make or break them, and work hard to grab this market. Spotify’s strongest initial growth was in Europe — it didn’t launch in the US market until it had 10m European users.

When you have a large user base you can set the de facto standards for an industry, says Lotito, which gives you a further advantage, in a virtuous circle. This is why, when Creandum, the Swedish VC firm that was an early Spotify, backer looks at new investments, it is always looking for startups with the ability to “own the customer” — whether in telemedicine or pet services, Creandum partner Staffan Helgasson told Sifted recently.

Marie Mawad is Sifted’s French correspondent. She also covers AI, and tweets from @Marie_a_Paris

Maija Palmer is Sifted’s innovation editor. She covers deeptech and corporate innovation, and tweets from @maijapalmer