Welcome to The Big Idea, where each week we pick a company with a weird, wacky or gamechanging notion that could have a massive impact on the world around us.

Next up is injectable implants: small devices that can sit in the body for decades, unlocking a world of information for users and scientists.

We’re used to the idea of wearable technology measuring everything from our temperature and heart rate, to blood glucose levels and sleep. But what if we moved those devices inside the body?

That’s what Swedish startup DSRuptive does, using small glass capsules — the size of a grain of rice.

On Wednesday, the company announced the results of the first clinical study showing the effectiveness of injectable implants in monitoring body temperature.

The results are a glimpse into a future when implants could be the norm for everything, from health monitoring to payments and identification.

What problem does it solve?

The problem with wearable tech like Fitbits and Apple watches, cofounder Hannes Sjoblad says, is they always cause a certain amount of friction for the user — you have to remember to wear them every day, you might have to take them off to swim or shower, you have to charge them, they might have to match your outfit.

“That’s not the case with the implant,” he says. “It’s in and it stays there, and you have a digital sensor platform that can sit there for twenty years. It’s just so convenient.”

Sjoblad has two implants. The first is a temperature sensor that sits next to his collarbone and the second is an identification device on his arm, which allows him to unlock his office — a product also sold by DSRuptive.

Implants are more precise than measuring things like your body temperature manually: thermometers can get different readings if inserted at different angles and are sensitive to a number of things — like if the person’s just consumed a hot drink.

How does it work?

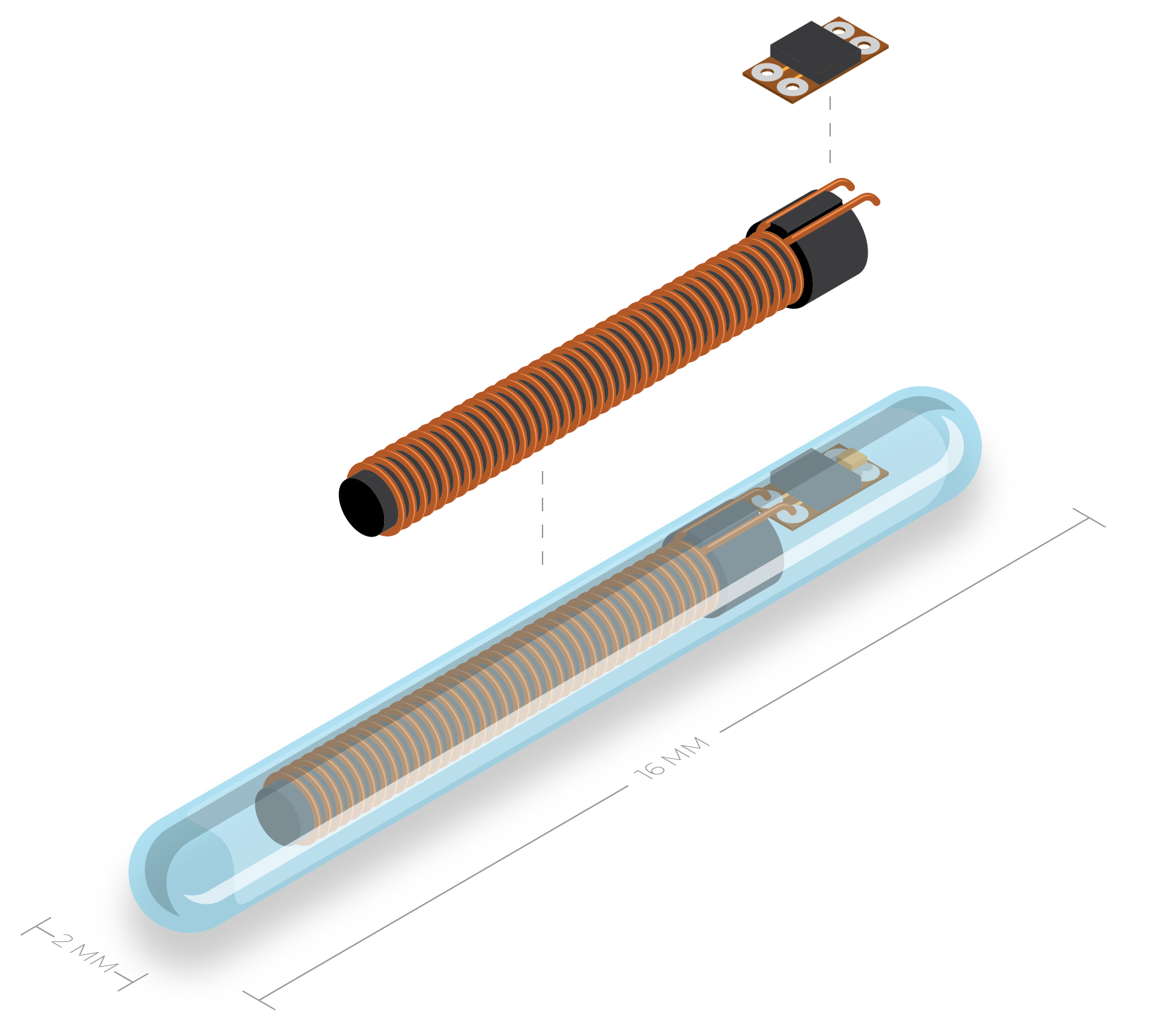

A small glass capsule is inserted under the skin, about the size of a grain of rice. They’re ‘biocompatible’, which means the body doesn’t attack or reject them, it just ignores them.

This biocompatibility has been proven across many years: injectable implants can be used on animals, Sjoblad says, as well as in the clinical study on humans.

Inside the glass capsule sit sensors. In the clinical study DSRuptive just completed, they used temperature sensors, but it could also be things like accelerometers to measure pulse or sensors to measure blood oxygenation.

There is a small amount of pain involved in the insertion of the device — in the clinical study people rated it two out of 10 on average in terms of pain.

To read the information from the sensor, users swipe it with a smartphone, which collects the data on an app.

What are the medical uses?

DSRuptive’s recent study is significant because it’s the first to show that implantable devices can effectively measure body temperature.

“We realised that no one had really tested them and shown what they can do, in a proper academic setting with clinical researchers,” Sjoblad says.

He says there are two medical use cases they’re currently pursuing.

The first is fertility. Companies like Natural Cycles are already using wearables to measure body temperature, as a way of tracking when ovulation occurs and working out when a woman is fertile. DSRuptive implants would make these measurements even easier for the user, Sjoblad says.

The second use case is in monitoring pandemics. A research team could implant groups of people in a specific location with temperature sensors, which then monitor the percentage of people with a fever.

“If a thousand people in the city have these devices, you can see the percentage of fever occurrence changing — like if it’s usually at 1-2% but it rises suddenly to 4 to 8%.”

There have been a couple of studies indicating wearables can predict an uptick in fevers 48 hours before a surge of people arrive at hospitals, for example. In places where Covid-19 is still particularly bad, DSRuptive implants could be used to alert hospitals to incoming waves of patients.

What are the risks?

“I’ve been part of implanting more than a thousand people and I’ve heard all kinds of questions regarding safety. Things like, can I be tracked and monitored, can someone hack me? The short answer is no,” says Sjoblad.

The devices couldn’t be used to track anyone, he says, because they don’t have a battery in them, they are passive devices, so they can’t transmit any information by themselves. “The only way to access an implant is to take a smartphone and touch it.”

There will be those, however, who determine the end vision of implanted devices as potentially more risky in terms of data: although DSRuptive’s implants are passive, other companies could develop devices that transmit or share information. That could be particularly concerning with sensitive health data.

What does the endgame look like?

Sjoblad is convinced that one day implants will give us access to a wealth of information about our own bodies. Beyond health monitoring, implants will become the norm for other applications, such as identification and payments.

“Imagine, instead of having keys, you just have an implant in your hand. And instead of having a wallet you have an implant that you swipe at the payment terminal, and then your Fitbit under your skin. Then there’s no clutter in your life, no handbag full of stuff, no stuff to forget in a taxi or at home when you’re in a rush,” he says.

“If you want to think of the world in 2030, I think having chip implants will be a normal thing.”