When a drone grounded close to 1000 flights at London’s Gatwick airport in the run-up to Christmas last year, it disrupted the travel plans of an estimated 140,000 passengers. But it also turbocharged a new industry: anti-drone defence systems.

“How do you stop a drone?” was a question repeatedly debated as people watched the 3-day drama unfold. Gatwick, in the end, brought in a military-grade jamming technology - called Drone Dome made by Rafael Defence Systems, a long-established Israeli defence contractor.

But a number of startups working anti-drone technologies are seeing a surge in interest, too.

“The phone hasn’t stopped ringing since then, it has gone crazy,” says Richard Gill, founder and CEO of Drone Defence, a UK-based startup developing geo-fence technology that detects drones and prevents them from flying over sensitive areas such as prisons by jamming the signal between drone and controller.

Drone Defence is a 2-year-old company set up by Gill, an former army officer who learned about drones while serving in Afghanistan. The company’s main reference client so far is Les Nicolles prison on the southern British Isle of Guernsey, where it set up a a jamming system - called SkyFence - to stop drones flying into the facility with drugs and other contraband.

Although the Les Nicolles project has been a success so far, with no drones getting through since the geofence was installed more than a year and a half ago, other UK sites have been slow to follow suit. This is in part because drone jamming technology is actually illegal in the UK- barring some exemptions - under the Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006. In Guernsey, deploying the system required a change of local law.

Gill has been waging a lonely campaign for a change in the law in the rest of the UK. Now, he believes there is momentum for such a change. In the wake of the Gatwick incident there are already plans to give UK police additional powers to land, seize and search drones. Gavin Williamson, UK defence secretary has said all airports should be investing in drone deterring technology.

Until the Gatwick incident there wasn’t a pounds, shillings and pence figure that companies could put on drone risk. Gatwick quantified the impact.

Companies are also becoming more interested in drone protection, says Gill.

“Until the Gatwick incident there wasn’t a pounds, shillings and pence figure that companies could put on drone risk. Gatwick quantified the impact is has on companies,” he says. EasyJet has said the Gatwick drone incident cost it £15m in passenger compensation.

Gill says his company, which has an annual turnover of £500,000 has sent out formal quotes to customers for five times that amount in the first few weeks of this year alone.

Among the businesses interested in drone mitigation are football clubs and festival organisers. Any large gathering of people is seen as potentially at risk from, for example a drone carrying a small bomb or chemical agent. Ahead of the 2018 Football World Cup in Russia, for example, the Russian military deployed military jamming technology at stadiums. Government buildings and facilities such as power stations that form part of critical national infrastructure are also increasingly interested in drone defences.

The UK’s Ministry of Justice is expected to shortly issue a tender - expected to be worth around £7m - for the protection of its sites, says Daren Wood, business development manager at Eclipse Digital Solutions, a UK-based provider of electronic intruder detection systems, including protection against drones. This could prove a kick start for the drone protection industry in the UK, says Wood.

Startups see niche in civilian drone defence market

Counter-drone technology has so far been mostly been in the hands of military hardware suppliers, such as Lockheed Martin, which has created a laser gun tower that can blast UAVs out of the sky. L3, another US defence company, has developed the Drone Guardian system which detects drones using radar and radio frequency monitoring, and blocks drone signals.

Such systems are expensive, however, and even the non-lethal technologies are often hard to use in non-combat environments. Military jamming equipment, for example, usually goes out in every direction, covering a large area. In an urban environment that would interfere with nearby wifi systems so it would be difficult to make these a permanent fixture. Civilian-focused anti-drone developers, such as Drone Defence, have spotted a niche in creating technology that is more precise and limited range to avoid interference.

In the US, San Diego-based startup Citadel has raised a total of $13.8m to help it develop its counter-drone technology, while San Francisco-based Dedrone, whose drone deterrent system is used to protect the New York Mets stadium, has raised $43.2m. Drone Defence was approached by investors, says Gill, but he declined the deal, preferring to grow the company further before taking external funding.

“We’re definitely interested in the drone space, including counter-drone technologies,” says Uzma Choudry, venture capital investor at Octopus Ventures. Choudry has been actively looking for startups to invest in. “The timing is perfect. Drone hardware is becoming available at a reasonable price and regulators such as the Civil Aviation Authority are becoming increasingly willing to grant commercial operators exemptions that allow them to operate. A lot of industries, are starting to see the value of using drones.”

Goldman Sachs estimates the drone market overall will be worth $100bn between 2016 and 2020, with the fastest growth coming from businesses and civil governments. As the number of drones grows, so too does the need for technologies to monitor and control them.

Other defences under development include unmanned aerial vehicles that can capture rogue drones in nets. Delft Dynamics, a 12-year-old Dutch company, for example, has developed the DroneCatcher, a drone which shoots out a net to capture adversaries in mid-air. Search Systems, a UK-based company that makes search and rescue drones, offers a drone called the Sparrowhawk, which can take down drones up to 20kg in weight with a net.

Insurance and monitoring technologies needed

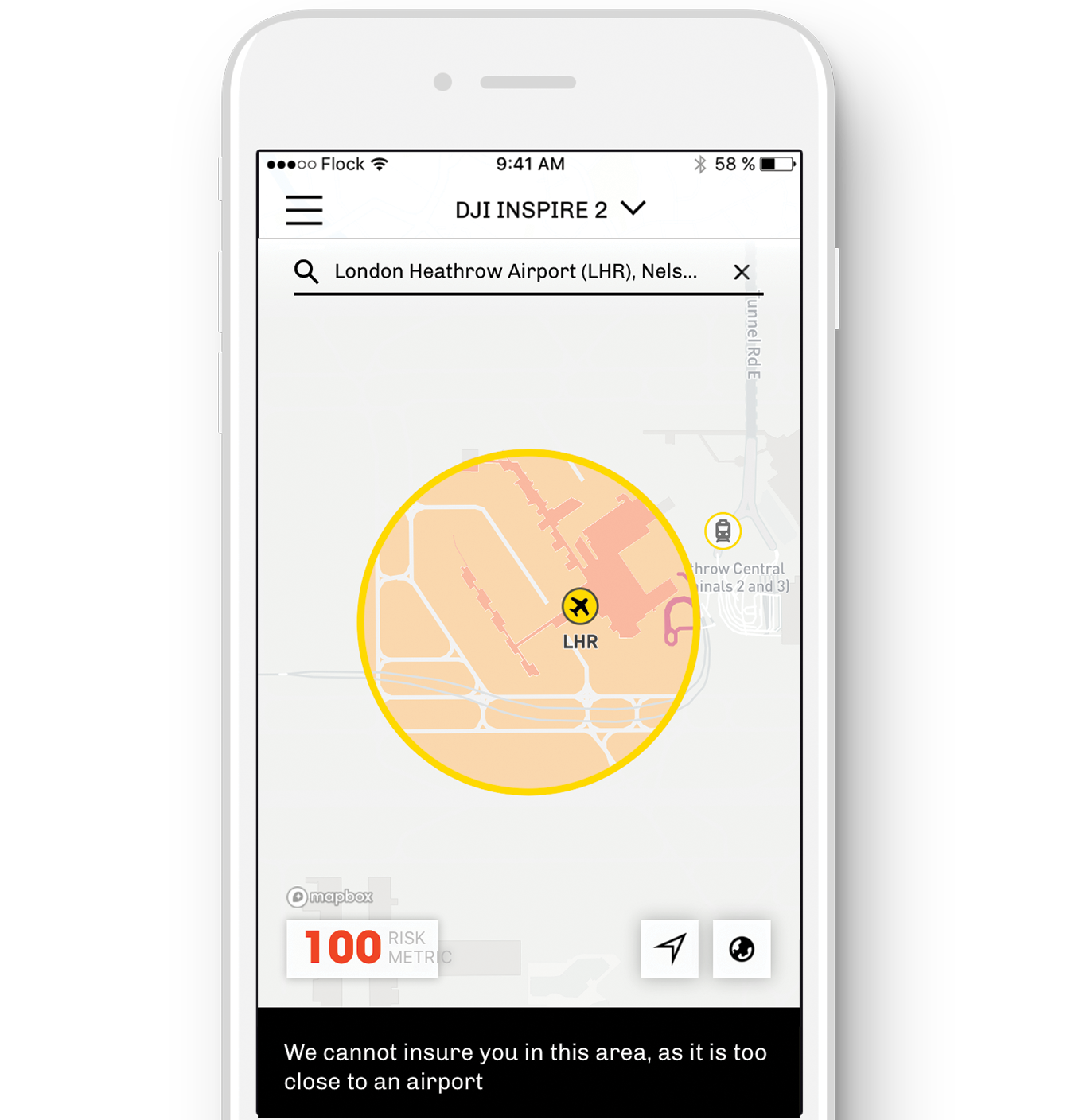

Increased scrutiny of the drone industry, post-Gatwick, is also likely to benefit companies like Altitude Angel, a UK startup that provides an air traffic control system for drones, and Flock, a UK company providing insurance for drone pilots. From November 30 this year anyone flying a drone above 250g in weight has to register on a Civil Aviation Authority database and complete an online safety test.

Antton Pena, founder of Flock, says tightening legislation is creating new interest in understanding risks and safe flying. As well as offering drone pilots a series of insurance options, Flock’s website provides information about how risky their flight plans are.

“We look at factors such as the population density, whether there are buildings such as prisons, power plants, schools or heliports nearby,” says Pena. Insurance premiums go up and down depending on when and where someone is planning to fly. It is a great opportunity to educate drone pilots, he says, adding: “In some cases we won’t insure you at all. For example if you fly too close to an airport.”